Historic centres worldwide are characterized for being an interest point for tourists, being this one of the main economic activities of these areas. Their urban pattern made up of narrow and sinuous streets, the historic buildings and characteristic monuments create the ideal environment for pedestrians to stroll, admire the built heritage, and recreate themselves with the local gastronomy, crafts, and festivals. These areas possess a higher level of protection than the rest of the city aiming to preserve the cultural values. The laws and regulations in place promote conservation on the one side, but can become an obstacle for the local residents to meet their needs, on the other.

The dichotomy between conservation policies and development needs has been magnified due to the ongoing health crisis of the COVID-19 pandemic, as the main economic drivers of these historic areas have been severely affected with the mobility restrictions. During the last months we have witnessed the emptiness of emblematic mass tourism sites like Venice, Dubrovnik, or Jerusalem resulting in the regeneration of nature and the environment, and the decline of the tourism sector. Gentrification indicators such as the number of Airbnb locations, the type of businesses that open or close, or the real estate prices have dramatically shifted provoking economic loss, social unrest and uncertain future for the old cities’ residents and workers way forward.

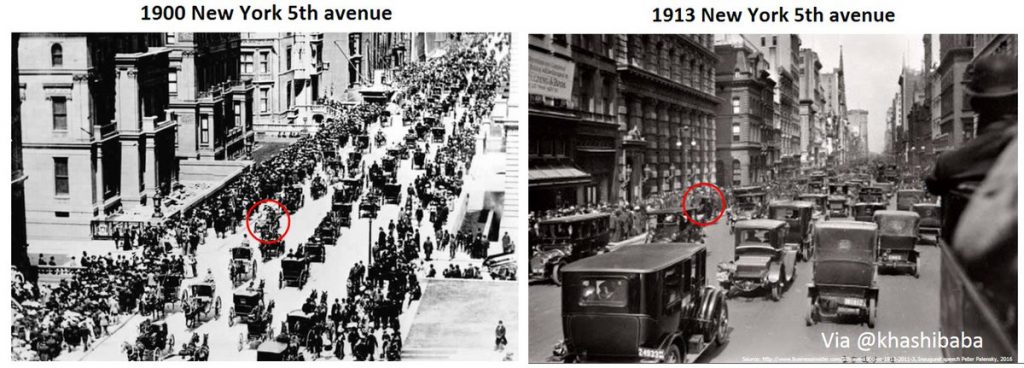

This phenomenon could be considered a period of disruptive change, a “non-localized future irreversible change that affects a portion of an industry”, that has been a constant in the evolution of cities (Smith, 2014). The way these changes are tackled depends on the type of disruption, the flexibility of the systems affected, and the willingness of the inhabitants to adjust (Gilbert & Bower, 2002). Taking as an example the city of New York and the advancements in the automotive industry, in just over a decade (1900 – 1913) the mode of transportation shifted from horse and carriage to engine cars (Hewitt, 2018) (See Figure 1.1)

The transition was successful mainly for two reasons: the flexibility of the road system and the general public enthusiasm to use the engine cars instead of the horse carriages. The flexibility of the urban fabric, having streets wide enough to include many lanes, facilitated the interaction between the two means of transportation, something unimaginable in a narrower street system like an old town. Moreover, the new transportation technology implied comfort, as well as less maintenance and reliance on horses, making it an attractive, rapid and highly accepted means of transport.

How cities absorb these disturbances depends on the adaptability of the city urban elements and its citizens, a constant process in the evolution of cities that face disruptive change periodically. In the present moment, old cities are going through a pause in their development, as managers, decision-makers, and the tourism sector wait for the mobility restrictions to be lifted, and for people to start traveling again. In many cases, this period of uncertainty has been used to refurbish infrastructure and monument maintenance, waiting for the “normality” to come back. Yet, the economic withdrawal, and impact in the tourism sector is far from recovering and remains in the hope of a new normality with diversification for socio-economic reliance becomes critical.

Nevertheless, assuming things will return to the previous situation seems naive, and rethinking the future of old cities with less reliance on tourism is becoming an urgent matter. In the same way as in New York of the 1900’s, we may be entering a disruptive change transition time where the significance, function and understanding of heritage is shifting. The new paradigm is likely to be based on local tourism, living historic cities, and the return of traditional businesses aims to support the residents’ needs, boost the local economy, and promote the liveability of historic centres. Transitioning from a mass tourism mindset towards a local one will create friction and find enemies among those not willing to let go, similarly to the New York horse and carriage drivers who saw their livelihood jeopardized.

Mathisa/Shutterstock

Daniele Aloisi/Shutterstock

Vittorio Zunino Celotto/Getty Images

The main question is if we are willing and prepared as a society to let go of the traditional conception of heritage and historic centres, and ready to explore the opportunities created by a pandemic that has pushed the limits of globalization, mobility, and social interrelations. The current uncertainty and stillness open a window to design the future with new parameters and values. Yet, managing the transition phase is key to advance in the adequate direction, and move away from business as usual and the past habits that led us to the present situation.

Lastly, to follow this train of thought, I would like to raise some questions for reflection and future debate:

- Are our cities flexible enough to absorb these changes?

- Is it plausible a society where the tourism horse-carriages coexist with the new paradigm engine cars?

- Do the existing frameworks and deals support the building of a new paradigm around the tourism sector and historic cities?

- And, finally, if the current moment turns out to be a pause in reality and the sector goes back to 2019 parameters, using the current disruption as an opportunity for building a future urban and tourism paradigm would definitely be something societies won’t regret.