The Great Green Wall – Source: https://www.greatgreenwall.org/about-great-green-wall

The Great Green Wall and the arid region of the American west i

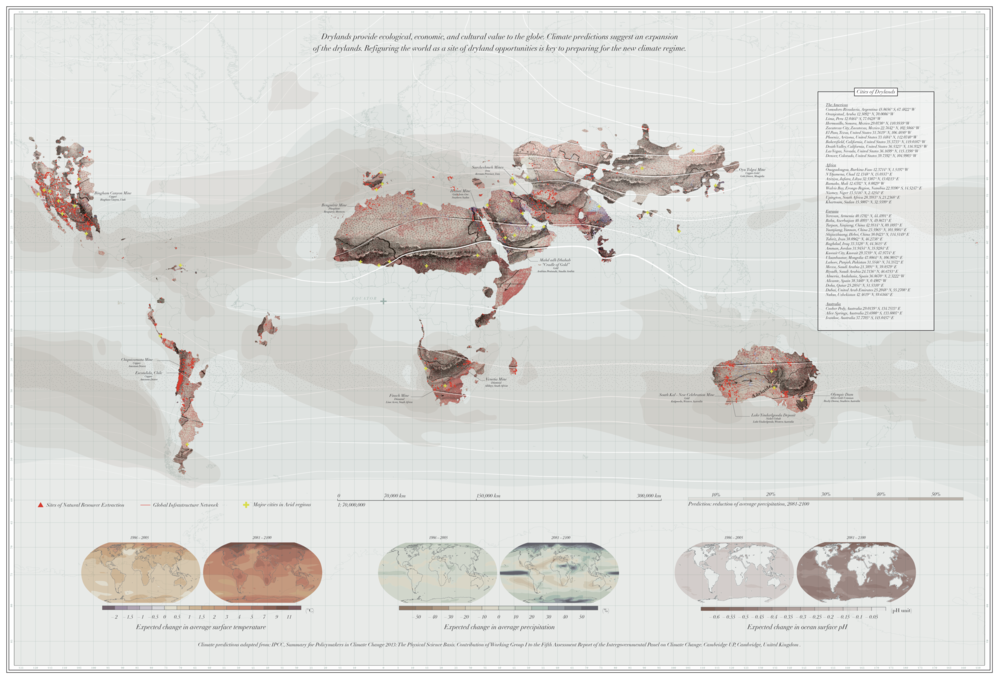

Arid landscapes compose more than one third of the earth’s surface (approximately 41% of the worlds land) with more than 2 billion people depending on the world’s arid and semi-arid regionii. Climate simulations based on observations of the past reveal a growing number of these areas for the years to come; due to climate change effects, arid lands will expand and occupy an even larger part of the global territory.iii

Driven by the mission to combat climate change, researchers, practitioners and policymakers over the past decades have shaped global dryland policy around an attempt to mitigate desertification. Amongst the most ambitious ongoing projects to combat this phenomenon is the Great Green Wall, a collaborative effort with more than 20 countries and international partners including the European Union, FAO and the UN Convention. Conceived in 2007, this project aims to create an 8.000 km long green corridor which horizontally transverses the African continent from the Western coast of Senegal to the eastern desert coasts of Djibouti with the aim to contain the expansion of the Sahara Desert in the Sahel region and greenify the arid lands. iv

The Great Green Wall transcending African territories, as presented by FAO Source: fao.org

Supporters of this initiative argue that by greenifying these territories, degraded landscapes will revive, preventing not only climate change but migration, famine and job insecurity.

On one hand, initiatives to intervene in the arid lands seem like a promising way to mitigate global climate challenges and provide resources to local communities. However, despite the projects being well-intentioned, there are both environmental and social parameters involved which, if not considered, risk of negative pitfall consequences. Below I aim to raise a series of main parameters pointed out by researchers, architects, and policymakers studying drylands. These reflections draw reference on both the ongoing attempts of desertification through the Great Green Wall and infrastructural irrigation projects realized during the 20th century in the American West and in particular the Glen Canyon Dam with the aim to raise some common concerns which have been overlooked when planning for the arid lands.

From an environmental perspective, afforestation, primarily through planting trees if carried on in areas that are not favorable to such conditions, can harm native ecosystems disrupting the soil and vegetation.v Also, the fact of intervening in the arid land itself must be carefully considered; arid lands are not wastelands but form part of a biome, vital for the global biosphere.vi

From a sociocultural perspective, there are two main aspects which need to be reconceptualized when planning for the arid lands. On one hand, western perceptions that suggest a reading of these lands as empty and barren and on the other, projections on the notion of place and placemaking deriving from planning and design cultures which often do not relate to these territories and the practices that have been practiced by indigenous populations.vii According to Davisvii, “the assumption that the world’s drylands are worthless, deforested, and overgrazed landscapes has led, since the colonial period, to programs and policies that have often systematically damaged dryland environments and marginalized large numbers of indigenous peoples, many of whom had been using the land sustainably.”

Even though societies have successfully inhabited these territories for centuries, the western imaginary on arid lands which favors green land over arid landscapes is prominent also in maps and visual representations of both real and imaginary places.viii Utopic and visionary representations of both the past and present rarely are shaped around arid lands. Instead, green spaces, in many cases surrounded by water tend to occupy a large area in illustrations of the spatial imaginary.

A later, colorful illustration of Thomas More’s Utopia Source: gabriellagiudici.it

While the recent discourses on combating desertification are shaped around greenification and afforestation, in the early 20th century of big infrastructural developments this was shaped around urban development, mobility and especially the engineering of water infrastructure. An interesting example of this is what occurred in the Arid Region of the United States where western lands were perceived as places for future expansion and resource exploitation through water engineering. ix In this short essay I aim to tackle a small part of these interventions in the arid lands through the lens of the Glen Canyon Dam construction.

Following the optimistic framework of the Hoover Dam (1935), that the desert can be redeemed and engineering is capable of deploying its control over nature, on October 1956, the construction of another Dam in the Colorado River, the Glen Canyon Dam began. Presented as the “colossus of the Upper Colorado River”, this project would collect water from all tributaries in the Upper Basin, except one small stream (Paria River). The Dam would rise 710 feet above bedrock between the vertical walls of massive red sandstone. This high, concrete-arch dam backs up water for 186 miles to form Lake Powell, the second largest reservoir in the United States. Accompanied by huge infrastructural projects, such as the 76-mile highway to Glen Canyon Dam from Utah, the 25-mile highway extending northward from Bitter Springs, and the construction of the highest steel arch bridge, crossing at the Glen Canyon Dam site, Glen Canyon Dam was constructed accompanied by a discourse on manifestation of political and economic power. In order to house the workers that would have to relocate in order to take part in this large operation, in 1958, land belonging to the Navajo tribe was exchanged for land in Utah to form the settlement of Page, initially called “Government Camp”.x

Right: Glen Canyon Dam, source: Bureau of Reclamation

Among the Dam’s benefits, the Government Office included the opportunities for recreation that the Reservoir of Lake Powell would create, the supply of water to municipalities and the growing industrial complexes, as well as the successful exploitation of the vast store of strategic minerals. Also, the powerplants installed in the Glen Canyon Dam, would help cope with the increasing demands of power needs and help with the costs of the program for development of the water resources of the Upper Basin.

As stated by the Department of Interior and the Bureau of Reclamation, Glen Canyon was built as a “benefit to all Americans”, investing in their future. “Whether you live in the city or on the farm, using water made available by the CRSP, or whether you come to fish, to go boating, or to just sightsee, the Colorado River Storage Project belongs to you and can be enjoyed by you”xi.

However, the intentions of following the optimistic discourse of the Hoover Dam and the “big era of the Dams”, reveal a more complex relationship between natural resources, cultural perceptions, and economic power in the case of Glen Canyon Dam. Soon, Glen Canyon Dam became anti – symbol of the emerging environmental movement and for many, it was perceived as a representation of arrogance and destructiveness towards nature. Edward Abbey, who was one of the first to oppose the construction of the Dam, wrote that Glen Canyon “was a portion of earth’s original Paradise”xii that is now irreplaceable.

Environmental reactions of that time, related more to the man – made invasion to the nature’s wonders and the poetics of the landscape and memory, whereas, contemporary environmental advocates, rely more on scientific data to advocate for the repurposing of the Glen Canyon Dam (huge evaporation and seepage losses, endangered species, sediment trapping).

There is another important socio-environmental aspect here that should not be ignored: the ecological changes and depletion of groundwater table that occurred in the Colorado river, inhibited many Navajo families from attaining food like they had in the past. To add to that, mining operations set up in these lands by coal, helium and uranium companies and the increase of recreational tourism, also imposed a series of sociocultural adaptations to the Native American population. xiii

The arid dryland policy and its consequences for both local and global population is a topic which would require a more thorough analysis than the one presented in this essay. However, the cases briefly addressed here can illustrate the complex dynamics underlying the planning of such landscapes which could be summarized in following points. First, the need to understand arid regions as coupled social and ecological systems. Second, the necessity to reevaluate global policy frameworks in drylands according to research carried on in these territories and consider the where, how and for whom afforestation or large-scale water infrastructure projects are planned for. Third, to move beyond mere technocratic solutions and neoliberal economic land policies and seek for systemic understandings of local dynamics and planetary implications. And finally, to learn from and adapt our action plans to practices of local communities ensuring those who manage arid territories will continue to do so successfully in the future.

References

[i] Preliminary research on this topic started in 2018 as part of the class Arid Landscapes with prof. Danika Cooper in the Master of Urban Design post-graduate program, at CED,UC Berkeley.

[ii] Nations, U. “Global drylands: a UN system-wide response. Prepared by the Environment Management Group.” (2011)

[iii] Feng, S., and Q. Fu. “Expansion of Global Drylands under a Warming Climate.” Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics 13, no. 19 (October 14, 2013): 10081–94. https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-13-10081-2013

[iv] https://www.greatgreenwall.org/about-great-green-wall, accessed 10.06.2021

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/sep/07/africa-great-green-wall-just-4-complete-over-halfway-through-schedule , accessed 10.06.2021

[v] Holl, Karen D., and Pedro H. S. Brancalion. “Tree Planting Is Not a Simple Solution.” Science 368, no. 6491 (May 8, 2020): 580–81. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba8232

[vi] Byrne M, Yeates DK, Joseph L, Kearney M, Bowler J, Williams MA, Cooper S, Donnellan SC, Keogh JS, Leys R, Melville J, Murphy DJ, Porch N, Wyrwoll KH. Birth of a biome: insights into the assembly and maintenance of the Australian arid zone biota. Mol Ecol. 2008 Oct;17(20):4398-417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03899.x. Epub 2008 Aug 27. PMID: 18761619.

[vii] Davis, Diana K. The arid lands: history, power, knowledge. MIT Press, 2016.

https://www.doaks.org/newsletter/reimagining-the-desert, accessed 10.06.2021

[viii] https://www.doaks.org/newsletter/reimagining-the-desert, accessed 10.06.2021

[ix] Starn, Frances Smith. “The Arid Region of the United States and Its Afterlife: Beyond the 100th Meridian.” Musings on Maps (blog), September 1, 2016. https://dabrownstein.com/2016/09/01/the-arid-region-of-the-united-states-and-its-after-life/.

[x] https://cityofpage.org/about-page/city-of-page-history, accessed 10.06.2021

[xi] https://www.usbr.gov/, last accessed 03.05.2018

[xii] Edward, Abbey. “Desert Solitaire: A Season in the Wilderness.” 1968

[xiii] https://grcahistory.org/sites/beyond-park-boundaries/navajo-reservation/ accessed 10.06.2021

[xiv] Cooper, Danika. “Waving the Magic Wand: An Argument for Reorganizing the Aridlands around Watersheds.” The Plan Journal, 2020, 22.