By Komal Potdar

UNESCO celebrated the 10th anniversary of the Historic Urban Landscape recommendations which were adopted in 2011 and took stock of learning and opportunities these guidelines and debates on the future of urban management, topics such as public space, renovations, tourism, infrastructure and livelihoods. This event was an effort to mainstream this underutilized UNESCO Recommendation and stressed on the significance of urban heritage toward sustainability of cities. The fact that out of the total 1154 inscriptions, over 300 properties are cities and over 500 properties located within historic urban cores underscores the critical role of HUL recommendations for sustainability and the need for integration to a higher degree within planning and design frameworks. The role of primary actors, decision makers, civil society and local-led urban recovery is key towards a coherent adaptation to suit the context and setting of the WH and advocate the SDG 11.4: “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage”.

The HUL recommendations propose four tools of civic engagement, knowledge and planning, regulatory systems and financial tools for innovative approaches to be adapted to local contexts by different stakeholders. This article is focused on the need for extensive and integrated documentation and mapping of cultural and natural characteristics which is beyond the protected areas of historic monuments and ensembles viewed as cultural heritage, and discussing a case in India.

The Indian preservation and conservation frameworks are fast evolving, however at a nascent stage as compared to the developed countries; the basic principles and fundamentals can be inferred to have borrowed from its colonizers. The Archeological Survey of India (ASI)[1], under the Ministry of Culture, currently protects and maintain over 3600 monuments (24 World Heritage cultural properties) and is regulated by the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains (Amendment and Validation) 2010. The precursor of this act was the 1904 Ancient Monuments Preservation Act in British India during the times of Lord Curzon. This amendment introduced a buffer of 100 meters for prohibited zones and 300 meters of regulated zones from the limit of the protected area of the protected monument. This amendment to the original AMASR Act was passed in 1958 and has been amended after five decades with an intention to the original act was proposed in view of the balance the needs of heritage an urban renewal, constituting of the National Monument Authority as a competent body to prepare heritage bye-laws to provide for improved management plans and controlled development and illegal encroachment. This buffer of 300 meters also served the purpose of the declaration of buffer zones for World Heritage nominations and most inscriptions after 2010 have such a legal buffer zones. This is primarily done to avoid any complications which arise due to many stakeholders and interests and of notifying large areas around the monument. However, I argue here that this may not be the best or the most suitable means of conserving the identity and with support of the HUL recommendations local structure of law and order has the potential to be strengthened. The following case study presents the challenges that Indian historic urban environments and burgeoning urbanization, industrialization, infrastructure developments and socio-economics that pose a threat and challenge for the protection of integrity and authenticity of monuments and how the need to consider the wider setting and beyond the protected limits is very crucial.

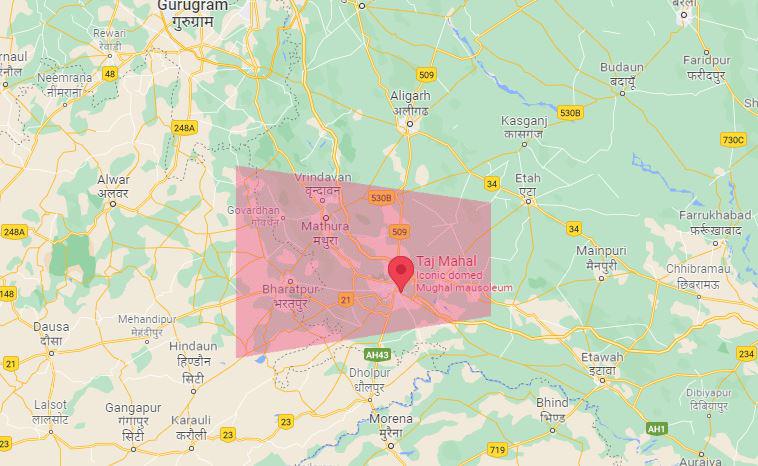

The Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ)[2]

The Taj Mahal gardens and its white marble mausoleum is one of the World’s most popular and visited cultural heritage sites. The city of Agra and the river Yamuna, the edge of the river where the mausoleum is located, is a case of a historic cultural landscape, replete National and State protected monuments, gardens. However, the 20th Century brought about industrialization and turned the Yamuna into one of the most polluted cities in India and factories making Agra world’s eighth-most polluted city. The Taj Mahal is often enveloped by dust and smog from smokestacks and vehicles. These outcomes and impacts of the external environment are beyond the control of ASI and conservation and management only addressed issues on a short term basis, since the environment of the monument did not change at all. The legal 100 meter and 300 m prohibited and regulated zones did not apply to the environmental conditions that affected the physical structure of the monument, due to events taking place 50 km away from its location. The year 1984 is the same year that the Taj Mahal was inscribed as the year in which a PIL (Public Interest Litigation) was lodged by environmentalist-lawyer M. C. Mehta. According to the petitioner, the foundries, chemical/hazardous industries and the refinery at Mathura are the major sources of damages to the Taj Mahal and needed urgent governmental environmental action. The Central Pollution Control Board delineated the Taj Trapezium Zone (TTZ), on the basis of the weighted mean wind speed in twelve directions from Agra to Mathura and Bharatpur. The boundaries of the zone were made keeping in mind the effect of any pollution source in this zone on the critical receptor- The Taj Mahal.

TTZ is an area of about 10,400 sq km spread over the districts of Agra, Firozabad, Mathura, Hathras and Etah in Uttar Pradesh and the Bharatpur district of Rajasthan, 20 tehsils (local unit of administrative division) and 38 blocks which are further divided into gram panchayat (a village governing cabinet of five members) and villages. Industrial/Refinery emissions, brick-kilns, vehicular traffic and generator-sets are primarily responsible for polluting the ambient air around Taj Trapezium (TTZ). The Agra – Mathura region (50 km distance) has witnessed rapid industrial development. Besides the positive socio-economic impacts, the environmental impacts are highly detrimental leading to water pollution and acidic emissions into the atmosphere at an alarming rate. The sulphur-dioxide emitted by the Mathura Refinery and the industries when combined with Oxygen – with the aid of moisture – in the atmosphere forms sulphuric acid called ‘Acid rain’ which has a corroding effect on the white marble[3]. The acids react with the calcium carbonate of the marble stone façade leaving a yellowish patch and corrosion and abrasion due to high particulate matter in the air causing irreversible damage. Amongst other industries, tanneries and small factories were heavily dependent on coal as major source of fuel, leading to increase in particulate matter in the air and cumulative effects of all pollutants are more damaging. The Comprehensive Environmental Management Plan (CEMP) 2013 by NEERI (National Environmental Engineering Research Institute)[4] which conducted deep research and stated policy recommendations for control of air pollution and sewage and waste water treatments for the TTZ area. Due to the petition, many refineries, foundries and small industries had to shut operations and move to more sustainable and less polluting means of production and fuel consumption. This area was declared as an ‘Air Pollution Protection Area’. A Vision Document and Site Management Plan[5] is being prepared by School of Planning and Architecture, New Delhi and the ASI, respectively, which is under review of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India.

The concern regarding the environmental threat to the Taj Mahal has been articulated in the landmark judgment of Hon’ble Justice Shri Kuldeep Singh dated 30/12/96,

“The Taj Mahal is threatened with deterioration and damage not only by the traditional causes of decay, but also by the changing social and economic conditions which aggravate the situation with even more formidable phenomena of damage and destruction.”

Since this landmark judgment, National Green Tribunal has allowed only small, micro and macro-level industries which are eco-friendly, non-polluting or necessary to secure essential amenities in the TTZ. The plying of electric vehicles to the Taj Mahal, control of pollution. Over the years, many other short term and long term regulations are put in place through co-operation of many actors and departments and stakeholders and Local, State and National level. The Archaeological Survey of India has carried out extensive conservation works to maintain the monument by conducting scientific works for cleaning, conservation, restoration as well landscape and horticulture in the complex. Along with these, many efforts to manage huge visitor footfall (over 5 million per year, before Covid-19 pandemic) is being undertaken and implemented successfully over the years.

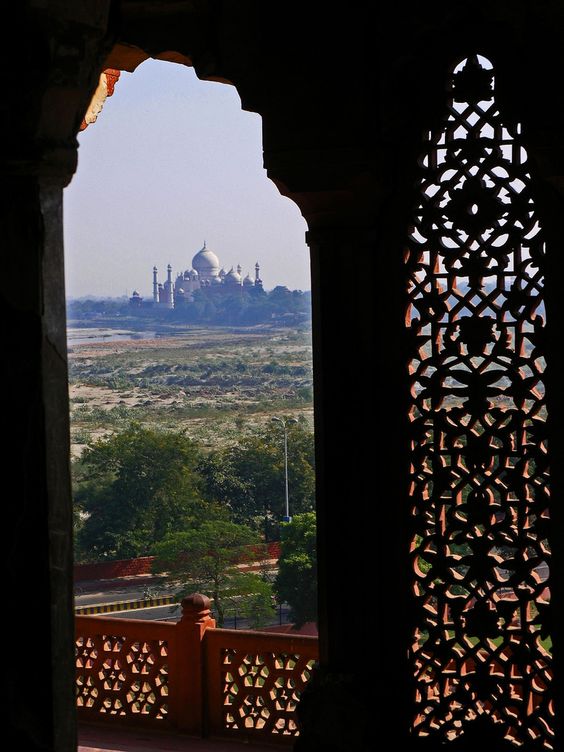

History and literature of this region and the Mughal Empire reveal the historical links of ‘spirit and feeling’ and cultural landscape significance between the Taj Mahal and the Agra fort, which is located approximately 2 km to the west of the Taj Mahal. During Shah Jahan’s reign, the 5th Mughal emperor, his kingdom reached the peak of its cultural glory and prowess. He was a military commander but was known best for his architectural achievements. His love for marble structures was evident from the new structures in the Agra fort, which was built by his grandfather Akbar. Jahan commissioned many monuments, the best known of which is the Taj Mahal in Agra, in which is entombed his favorite wife, Mumtaz Mahal. After Shah Jahan fell seriously ill, the war of succession began between his four sons; Aurangzeb emerged as the leader and overtook his father’s throne. After recovery, Shah Jahan was put under house arrest in Agra fort until his death. It is said that the cell in the fort where Shah Jahan was in captivity had the view of the Taj Mahal. After his death, Shah Jahan was too buried in the Taj Mahal. At present these two monuments are World Heritage properties which lie along the cultural landscape of historic Agra city and the River Yamuna.

The UNESCO State of Conservation reports[6] acknowledge the growing pressure on the OUV of this monument due to the urban development and increased tourism infrastructure. The proposal of the ‘Taj Heritage Corridor project THC’ [7]. The project was envisaged to develop the vacant piece of low lying land along the bank of the river and connecting the Taj Mahal and the Agra Fort. The $24 million project was planned and designed as a tourism generator and booster to provide swanky amenities which included shopping malls, amusement park amongst others. This grandiose and ambitious scheme came under the critical scrutiny of the TTZ as it violated several regulations and stipulations by the SC and raised environmental and cultural heritage concerns. The project was brought to a halt after evaluation and the potential threat to the environment and integrity of this World Heritage site. The UNESCO Reactive Monitoring Mission recommended a development plan for this area to prevent the proposal of such projects again and cleaning the river and preventing its use as a sewage canal should become a priority in this stretch. At present, this vacant land is being developed as a horticulture area and efforts geared towards its maintenance by the Agra Development Authority ADA[8].

Taking cues from the UNESCO HUL recommendations and its emphasis on the wider context includes notably the site’s topography, natural features, its built environment, perceptions and visual relationships[9] are amongst the other important characteristics to be included in the decision making processes. The TTZ is a good case example which not only is centered about the cultural heritage about also addressing issues of contemporary cities and development. Amongst the critical six steps, the appropriate partnerships, local management frameworks and developing mechanisms for coordination for the successful implementation of HUL method is key and is observed in the case of the TTZ. The TTZ and the PIL was and is a landmark environmental activism which underscores the immense value of long term vision towards regulation and governmental action eventually shaping the bye-laws and legislative framework, national and local together. The TTZ case and the World Heritage property of Taj Mahal worked as a catalyst for leveraging environmental, economic, social sustainable solutions with culture at the core of its approach and provide good learning opportunities for adoption of the HUL recommendations.

This article aims to stress the importance or the lack thereof of buffer zones and boundaries and emphasizes the need for an integrated and inclusive approach addressing all significant relevant characteristics and attributes linked to our history, society and world at large. To end the article on a poetic note, I quote the following lyrics acknowledging the inability of boundaries and buffers zones for our environment and its components of air, water, fauna, and the only apply for human and perceptions and their regulated worlds.

Note: The author was a former in house consultant to the Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi and involved in the preparation of the Site Management Plan from the direction of the Hon’ble Supreme Court of India. Views, observations and inferences presented here are in individual capacity and are in no connection to the institutions and stakeholders of the ongoing works.

[1] Archaeological Survey of India; http://asiegov.gov.in/

[2] Taj Trapezium Zone Pollution(Prevention and Control) Authority; www.ttzagra.com

[3] M. C. Mehta (Taj Trapezium Matter) Vs Union of India and Others Writ Petition (C) No. 13381 of 1984 (Kuldip Singh, Faizanuddin JJ) 30.12.1996 JUDGMENT; http://www.ttzagra.com/docs/SupreemCourtOrders/Order%2030-12-1996.pdf

[4] Petitioner: M.C. Mehta vs. respondent: Union of India & ors. Date of judgment: 30/12/1996 Bench: Kuldip Singh, Faizanuddin act: Headnote: judgment: https://main.sci.gov.in/judgment/judis/14555.pdf

[5] Scientific cleaning & conservation plan designed by ASI to protect Taj Mahal; https://www.business-standard.com/article/pti-stories/scientific-cleaning-conservation-plan-designed-by-asi-to-protect-taj-mahal-govt-118122100757_1.html

[6] State of Conservation reports for UNESCO; https://whc.unesco.org/en/soc/1452

[7] Taj corridor project compromises heritage; https://www.downtoearth.org.in/news/taj-corridor-project-compromises-heritage-13241

[8] Agra Development Authority; http://www.adaagra.in/TajMahal.html

[9] UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape Recommendations 2011