The Biennale Architettura, a celebrated international exhibition featuring forefront architectural research and practice from sixty countries, was held in Venice from spring to autumn 2021. It was curated by architect Hashim Sarkis, and contributions revolved around the thematic question How will we live together?.[1] This is, admittedly, a good question – although, as Hashim Sarkis argued, somewhat ironic given the isolation brought by the pandemic. Indeed, after a one-year postponement due to the outbreak of COVID, the feeling of disruption was still vivid throughout the event. The empty and incomplete pavilions of non-European countries embodied the impossibility to cross borders; and many exhibits reflected the darkness of the last few years. At the same time, the strengths of the exhibition were owed exactly to the engagement of featured projects with collective struggles, and perhaps more importantly with collective claims of our times. However, in an era when “we are running out of both space and time”[2] what becomes obvious is that these overarching claims can only be addressed with a variety of tools and collaborations. While architects and designers possess unique skills of visualization and problem solving, they sometimes lack the deep analytical qualities developed within the humanities and social sciences.

I write this blog as a reminder of the importance to open free-flowing communication channels between disciplines. I do so by discussing eight among the exhibited projects of the 2021 Biennale, which present affinities with current research threads in the fields of heritage studies.

Dismantling heritage

Many projects engaged with the constant flux of materials, people, and ideas, which confuses long-standing concepts of building, place, and heritage. The exhibition of the Japanese pavilion played with the notion of moving, functioning as a comment on mass consumption and reuse. The 65-year-old Takamizawa residence, about to be demolished in Japan, was transferred to Venice. Parts of it were erected on the terrace of the Japanese pavilion; other elements were carefully documented and exhibited inside the pavilion (Fig. 1). The dismantled building will continue its journey towards Norway, where it will function as a community facility.[3] In viewing parts of the building outside of their context, and in conceptualizing its different functions (residence, exhibit, community center), one perceives different relationships between the authentic and the reproducible, the tangible and the intangible, the local and the global, the valuable and the useless, ‘ours’ and ‘theirs’. Conventional concepts, roles, and practices of heritage management can no longer stand.

Figure 1: The exhibition of the Japanese pavilion, titled “Trajectories of elements: the co-ownership of action” and curated by Kadowaki Kozo

Heritage in the Anthropocene

Indeed, new research areas for heritage studies necessarily open with the urgency of the socioenvironmental crisis. The same goes for architecture: for Fei-Fei Zhou, the visualization and representation tools developed within design disciplines allow for “alternative spatial analyses of the Anthropocene.”[4] Previously overlooked transformations, such as productive areas, infrastructure planning, and industrial landscapes, become understood as aspects of the terraforming of the planet. Substantial research on the configuration of worldwide urbanization patterns is being carried out by ETH Zurich and the Urban Theory Lab. [5] Their visualizations, under the title Worlds of planetary urbanization explore anthropogenic expansion on the planet (including remote areas, wildlands, and oceans). In this spatial context, heritage can be perceived as a process of understanding the entanglement of different landscapes, and of engaging with their identities and potential futures. A localized example of that is the Serbian contribution, which focuses on the industrial city of Bor.[6] The exhibition explores the relationships of mining production, capital flows, and identity building; in other words, between earth, networks, and emerging heritages (Fig.2).

Heritages of exile

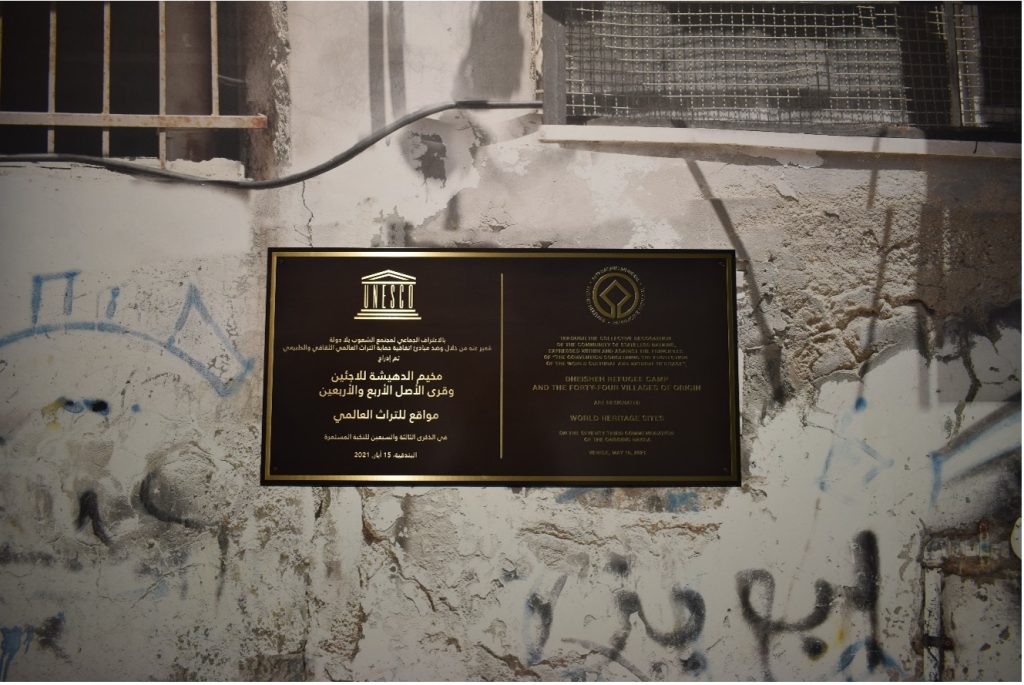

Another aspect of globalized life that marks new conceptual possibilities and uses for heritage concerns the temporalities and spatialities of uprooted communities. DAAR- Decolonizing Art Architecture Research experiments with the potentiality of nominating the Dheisheh Refugee Camp as a World Heritage Site, observing that there might be new values associated with such sites that need to be acknowledged and protected. Through this symbolic nomination of an assumingly temporary site, they search for new understandings of heritage, and its creative potentials to challenge the status quo. They write:

We must understand refugees as being in exile and exile as a current political practice capable of challenging the status quo. Recognizing the heritage of a culture of exile is the perspective from which social, spatial, and political structures can be imagined and experienced beyond the idea of the nation-state.[7]

Perhaps the most important exhibited work related to the condition of refugees is being carried out by Forensic Architecture. In their project Forensic Oceanography, they look at the audiovisual materials produced by NGOs working with the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean; the opaque world of state violence is becoming representable, and obliges us to engage with ethical and political challenges.[8] In perceiving such structures and representations as collective heritage, new practices of care, empathy, and solidarity can emerge.

Strategies for survival

The urgency of the socioenvironmental crisis asks for new forms of living and governing the territories. For some among the exhibited projects, the key word is adaptation. Future Island, a public art and research project, attempts the artificial heating of a piece of land to a temperature up to 5°C warmer than its surroundings and observes the gradual adaptation of its living and geological agents (Fig.4).[9] For others, the overarching strategy is reconnection between people and environments. Through a complex installation based on a cyclic water system, the curators of the Danish pavilion put forward “the potential for a new world view that not only assigns value based on economic growth but sees wealth in variation, (bio) diversity and connectedness”.[10] Other teams stress the need for new forms of governance: Future Assembly, a collaboration between artists, researchers, and activists in the fields of human rights and climate justice, was inspired by the institution of the United Nations. It seeks to establish the rights of non-human actors, by acknowledging that humans and non-humans, “the fellow companions who sustain our planet” all have a stake in its future. [11] Adaptation, reconnection, and governance are all important directions in contemporary heritage studies, which see heritage as a future-oriented relationship between humans, non-humans, and landscapes.

Working together

Such a relationship is powerfully visualized in Refuge for Resurgence is a multispecies dinner taking place after the end of the world. As its creators describe:

Having survived Earth’s abrupt shift to an era of precarious climate, a multi-species community gathers in the blasted ruins of modernity to find new ways of living together. Working together to carve a new world out of the smouldering remains of the old. Working together to forge enduring forms of sharing and survival. Working together to forge enduring forms of sharing and survival. Working together to revive this land; this land once a place of order and control.[12]

I want to use this installation as an opportunity to comment on the role of such exhibitions (and by extension of arts and humanities) in this damaged planet. A stroll in any Biennale proves that architects can create worlds of wonder, consisting of unique spatial experiences and clever installations. At the same time, several teams do substantial work, in collaboration with marginalized communities, activists, or policymakers. But when viewed all at once, these projects risk assimilating a spectacle, an exercise in creativity directed towards very specific audiences. Of course, the used concepts and vocabularies are embedded in a wider emphasis on narratives of crisis and coexistence, present in many disciplinary areas. The contribution of heritage studies, a field concerned with temporality and with communities, can be seminal in this shift. But while the imagined roles for heritage studies and architecture are changing, both disciplines often remain self-referential and seek to avoid political conflict. However socioenvironmental crises are not exercises for design or methodology: they are inherently political. Systemic failures need to be addressed in direct and collective ways. If we are to contribute anything beyond our personal legacies, we must work in truly interdisciplinary ways. Interdisciplinarity here does not suggest that everyone can do everything; instead, it looks at the value of strategic collaborations between researchers, activists, and professionals, with different sets of skills, but with converging aims to act and to survive.

All pictures are taken by the author.

[1] More information on the event and the discussed projects can be found on the site of the exhibition: https://www.labiennale.org/en/architecture/2021

[2] Geographer David Harvey argued that “we’re running out of both space and time right now” in: David Denvir, “Why Marx’s Capital Still Matters. An Interview with David Harvey”, Jacobin magazine. Published 07.12.2018, accessed 27.01.2022, https://jacobinmag.com/2018/07/karl-marx-capital-david-harvey

[3] For more information on the exhibition, see Andreea Cutieru, “The Japanese Pavilion at the 2021 Venice Biennale Addresses Mass Consumption and Reusability”, Archdaily. Published 12.05.2021, accessed 27.01.2022

[4] The extract can be found in: Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing et al., Feral Atlas the More-than-Human Anthropocene, 2020, http://feralatlas.org.

[5] For more, look at the website of the projects https://planetaryurbanisation.ethz.ch/ (Accessed 27.01.2022)

[6] About the Serbian Pavilion, see https://www.e-flux.com/announcements/413706/8th-kilometer/ (Accessed 27.01.2022)

[7] From the website of the project http://www.decolonizing.ps/site/ (Accessed 27.01.2022)

[8] As the researchers write, “the impact of the presence of rescue NGOs on the aesthetic regime operating at the maritime borders of Europe can be measured against the controlled invisibilisation of border violence operated by state agencies.” Read more about this important project in https://forensic-architecture.org/category/forensic-oceanography (Accessed 27.01.2022)

[9] For a more extensive explanation, see https://www.future-island.org/ (Accessed 27.01.2022)

[10] For more on the pavilion of Denmark, created by Lundgaard & Tranberg architects, and curator Marianne Krogh, see https://dac.dk/en/press/architecture-biennale-2021/ (Accessed 27.01.2022)

[11] Future Assembly was created by Studio Other Spaces in collaboration with activists and academics in the fields of art, human rights, climate justice. Find out more in https://studiootherspaces.net/futureassembly/

[12] Refuge for resurgence by Superflux is “an invocation and a prayer for a different kind of world.” An extensive description can be found in https://creatures-eu.org/productions/refuge/