Figure 1. (Cover photo). Map showing Biafra (as declared in 1967) and Nigeria in the context of West Africa (source: Eric Gaba, Wikimedia Commons).

By Stanley Jachike Onyemechalu

Introduction

History and collective memory are critical for proper heritage interpretation, especially when it relates to war. Hence, where there is a poor reading of war history or where the history of war has been systematically diminished, the wartime heritage and its interpretation suffer. This is the case in Nigeria, where the history of its civil war – also referred to as the Biafra War (1967-1970) – has been largely suppressed or rather, systematically diminished. Nigeria’s civil war, which began in response to the secession attempt by the now-defunct Eastern region into the Biafran Republic, was Africa’s first post-colonial large-scale armed conflict. The 30-month war, which caused the death and displacement of millions of people, ended in the surrender of the breakaway Biafran side and its reincorporation into Nigeria.

Since the Biafra war ended, successive Nigerian governments have continued to stifle the war history and its memorialisation, perhaps in a bid to bury the ‘ugly’ past and avoid self-reckoning in favour of a reinvented national identity. It did not help that the war ended without a Truth and Reconciliation Commission or any formal government effort towards national post-conflict reconciliation. The closest attempt was the failed ‘3Rs’ (Reconciliation, Reconstruction & Rehabilitation) Policy – announced in the now-infamous ‘No victor, no vanquished’ speech by the then-military Head of State, General Yakubu Gowon – which has been heavily criticised in the many post-war historical and political commentaries on Nigeria. Of course, the suppression of violent memories in favour of grand national narratives invented by dominant political actors is not unique to Nigeria and its civil war memory. For example, see cases in Kenya, South Africa, Liberia & Uganda, where various avenues have been employed towards the silencing of violent memories. In Nigeria, there have been frequent interruptions to the teaching of History in secondary schools, including its complete removal from schools’ curricula in 2007 and subsequent reintroduction over a decade later (Orunbon, 2019). Additionally, the country’s National War Museum has been shown to be fraught with representational problems in the way it portrays the war, not least due to the overbearing influence of the Nigerian Military on the museum’s administration (Emeafor & Onyemechalu, 2021). Consequently, there is a gap in knowledge of Nigeria’s civil war history and its legacies, especially among the younger population. Paradoxically, this has spurred (or coincided with) increasing people-led efforts to ‘salvage the situation’ via visual representations in museums and through digital media (especially social media), resulting in dissonant narratives of the Biafra war and the misinterpretation and weaponization of its wartime heritage by parochial interest groups.

As the Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Viet Thanh Nguyen, once said “All wars are fought twice; the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory,” hence, it is important to understand how ‘memory battles’ are waged against affected communities by the State long after the conflict may have subsided or ended. Yet, among the many studies on the complex relationship between conflict and heritage – often referred to as ‘conflict-heritage’ studies – very little has been written about wartime heritage interpretation and the role of memory or history in that. For example, how might the suppression of war history impact wartime heritage interpretations, especially among the younger generation? To address this question, I share preliminary insights from the Legacies of Biafra Heritage Project (LBHP) – an offshoot from my ongoing PhD research on the intersection of cultural heritage and the legacies of 20th-century armed conflicts in the context of the Biafra war in Igboland, Nigeria. The overall aim of the LBHP is to explore the level of intergenerational knowledge/memory transfer of the Biafra War among young people (age 16-35) in Igboland of south-eastern Nigeria and how this might impact their heritage interpretations of the Biafra War. The project does this by (i) exploring how young people in Igboland perceive the heritage interpretation of the Biafra war, and what sources feed these perceptions; (ii) exploring how museums and other ‘agents of memory’ employ new media and visual representations to bridge the gap (created by the government) in knowledge of the Biafra war history, and how this might impact the heritage interpretation of the war. Over 300 questionnaires were distributed across 10 schools (eight secondary schools and two universities) to students between 16-35. Also, the sites of two prominent museums on the Biafra War – National War Museum, Umuahia (NWMU) and Centre for Memories, Enugu (CFME) – were visited and several interviews were conducted with key staff.

Preliminary Findings

The study found that the younger generation’s interpretation of the Biafra war heritage was influenced by the sources of their war history – including books, movies, internet/social media, and stories from parents/elders. The survey found that while the majority (98%) of young people had heard of the Biafra war, only very few (12%) of them could give a considerable account of the war’s history. Also, when asked how they had come to hear about the war, ‘school lessons’ and ‘books/movies’ accounted for 4% and 11% respectively, while ‘parents/elders’ and ‘internet/social media’ accounted for 68% and 27%. These suggest that young people are more likely to learn about the Biafra war from their parents (including older family relatives) or the internet than from school lessons, books or movies. Make no mistake, there are numerous movies and books – fiction and non-fiction – that have been written on Nigeria’s civil war. But if these books are not used in schools to teach war history – or since History is rarely even taught – then only personal motivation would make young people go seek and read these books. The Nigerian government has, for a long time, suppressed the history of the Biafra War in its curriculum and even where History was taught, the section on the Biafra War was not accorded considerable attention.

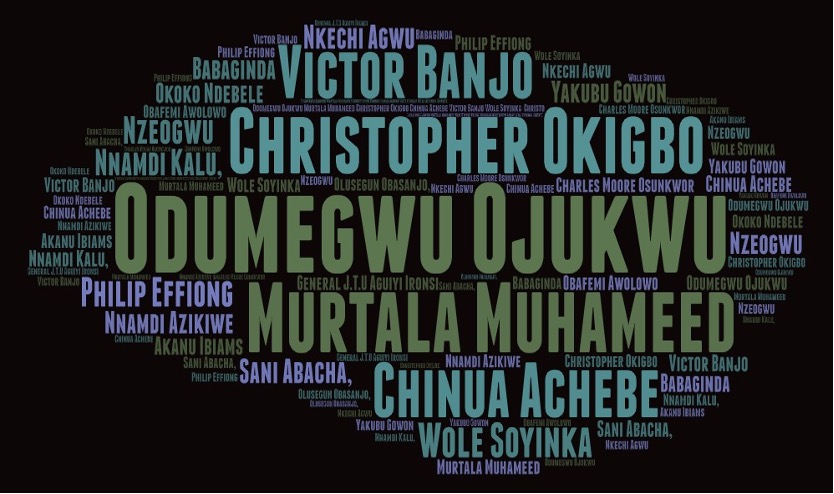

An interesting part of the survey is the responses that emerged when the respondents were asked to mention key personalities that they knew or had heard of from the Biafra War. The word cloud that emerged (see image above) showed that certain names from the war were remembered more than others, while certain names which had nothing to do with the war were mentioned repeatedly. For example, while Odumegwu Ojukwu – the leader of the secessionist Biafran Republic – and his deputy, Philip Effiong, were mentioned repeatedly, the name of Yakubu Gowon – leader of the Nigerian Armed Forces during the war – was relegated to the ‘fringes of memory’. Additionally, notable names like Chinua Achebe, Wole Soyinka and Christopher Okigbo – all of whom were very vocal during the war – were also well-mentioned. It was puzzling, though not surprising, however, to see the name ‘Nnamdi Kanu’ – who played no role in the war and was barely three years old when it ended in 1970 – appear in some of the responses. Mr. Kanu is the leader of the Indigenous Peoples of Biafra (IPOB) – a resurgent pro-Biafra group with strong diasporic connections and influence – so, only a lack of history might understand why some young people would mistake him as one of the key personalities from the war.

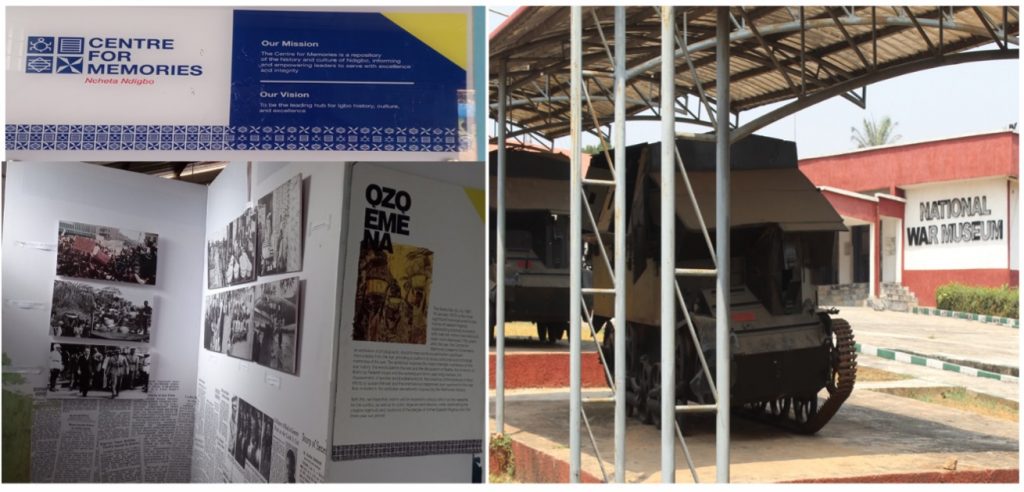

In exploring how the Biafra War history and heritage are (re)presented today, the study found that while the National War Museum exists to foreground the federal government’s heritage interpretation of the Biafra War, the youth-led community-driven Centre for Memories exists to address the representational gaps and counter the narratives in the former through its visual representations and social media activities. Additionally, the study found that, unlike the National War Museum, the Centre for Memories goes beyond its permanent exhibition on the war and employs social media, particularly Twitter, where they host several programs to connect with and conscientize the younger generation on other aspects of the war that are not necessarily found in their exhibitions. Nonetheless, organisations like the Centre for Memories can only do so much without any direct support from the government. No doubt, many efforts are now coming onboard to help teach the history of and memorialise the Biafra war, especially online, yet things would move a lot faster if the government would recognise the importance of preserving its war history and heritage in building a nation, where there is peace and justice.

Final Thoughts

The Biafra War remains a central and indisputable fact of Nigeria’s past, yet there seems to be an intentional failure to remember or talk about what really happened. Diminished or silenced narratives of key historical events, such as war, give rise to contested pasts and the misinterpretation of wartime heritage. in this case, the Nigerian government manufactures and sustains the misinterpretation of its war heritage through the suppression of history and the politics of memorialization. Nigeria’s government needs to reintroduce a comprehensive account of the war in schools and make the teaching of History a mandatory independent subject until about senior secondary class. Additionally, the government needs to disengage or disentangle its military from the administration of the National War Museum and allow the curators and other experts who work there to assume full control of their exhibition. This would allow for a democratic reckoning and interpretation of its wartime heritage, rather than the current ‘authoritative’/militarist approach.

Although the Legacies of Biafra Heritage Project is still ongoing, and more surveys and methods will be explored in the future to address more questions, these preliminary results discussed above show the significance of historical accuracy and awareness for proper wartime heritage interpretation, especially among the younger generation. One can argue, therefore, that wartime heritage interpretation is a product of the prevailing historical narratives – or lack thereof – surrounding it. Finally, remembering Nguyen’s words that “all wars are fought twice; the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory”, we must concern ourselves with how the (ab)use of post-conflict memories transform the heritage landscape of affected communities to forestall violent futures.

Bibliography

Orunbon, A. (2019, October 25). FG Should Reintroduce History In School Curriculum. Vanguard. https://dailytrust.com/fg-should-reintroduce-history-in-school-curriculum/

Emeafor, O. F. and Onyemechalu, S. J. (2021) Objectivity in Museums: The Nigeria Civil War according to the National War Museum, Umuahia. The International Journal of The Inclusive Museum, 14 (1), pp. 49 – 70. https://doi.org/10. 18848/1835-2014/CGP/v14i01/49-70

Miyonga, R. (2023) ‘We Kept Them to Remember’: Tin Trunk Archives and the Emotional History of the Mau Mau War, History Workshop Journal. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbad010

Hughes, H. (2023) Public Histories in South Africa: Between Contest and Reconciliation. Public History Review, 30, pp. 31–42. https://doi.org/10.5130/phrj.v30i0.8374

Glucksam, N. (2022) Accountability after Mass Atrocities: Political Contestation or Conceptual Dissonance? Journal for Peace and Justice Studies, 31 (1), pp. 46 – 64. https://doi.org/10.5840/peacejustice20223113

Kobo, O. M. (2020, January). “No Victor and No Vanquished” – Fifty Years after the Biafran War. Origins. https://origins.osu.edu/milestones/nigerian-civil-war-biafra-anniversary?language_content_entity=en

Korieh, C. (ed.) (2021) New Perspectives on the Nigeria-Biafra War: No Victor, No Vanquished. London: Lexington Books.

About the author

Stanley Jachike Onyemechalu is a Gates Cambridge Scholar and PhD Candidate in Archaeology at King’s College, University of Cambridge, UK. His research, which was awarded the Emslie Horniman Anthropological Scholarship Fund by the Royal Anthropological Institute, explores the intersections of cultural heritage and the legacies of violent conflicts in the context of the Nigeria-Biafra war (1967-1970) in Igboland, Nigeria. He is the current Book Reviews Editor for the Archaeological Review from Cambridge (ARC) and has a Lectureship in Archaeology and Heritage Studies with the University of Nigeria. Stanley is also co-editor of the forthcoming volume, ‘Archaeology and the Publics’, for the ARC. His research interests cut across (post-)Conflict Memory, (post-) conflict heritage, Indigenous and Decolonial Heritage, Museum Studies, and Community Archaeology.

Contact Stanley Jachike Onyemechalu: sjo50@cam.ac.uk

Acknowledgement

Check on the “Understanding Wartime Narratives in the Digital Age” conference’s website here.