By Karlijn Hulshof

The 1990s wars marked the end of Yugoslavia. The rise of national identities that accompanied the wars caused a significant change in the perception of culture. Consequently, heritage was one of the targets during the wars and especially religious heritage was under threat since religion is closely related to nationality in the region. After the wars, religious sites have for instance become places where victims are commemorated and that house monuments to honour them.

In 1995, Bosnia and Herzegovina split up into two entities after the signing of the Dayton Accords, see the the map below. Banja Luka was the first city I visited in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 2022. It is the second-largest city in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the capital of the entity of Republika Srpska. The other entity is the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina with Sarajevo as its capital.

The split of the country into these entities became, aside from a geographical split, a kind of cultural division. In this blog, I want to take you through my impressions of Banja Luka (mostly focused on the Ferhadija mosque) and at the end highlight questions and thoughts that have arisen throughout the research process.

The Ferhadija during a conflict

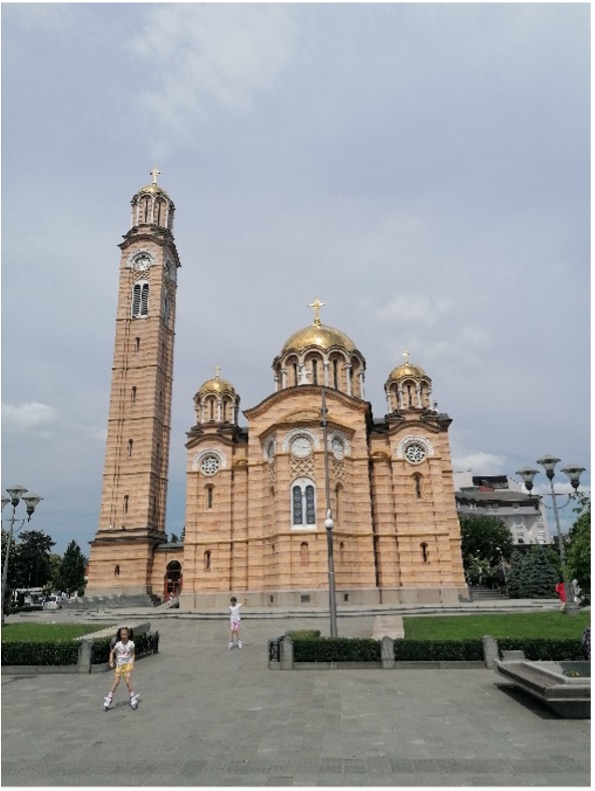

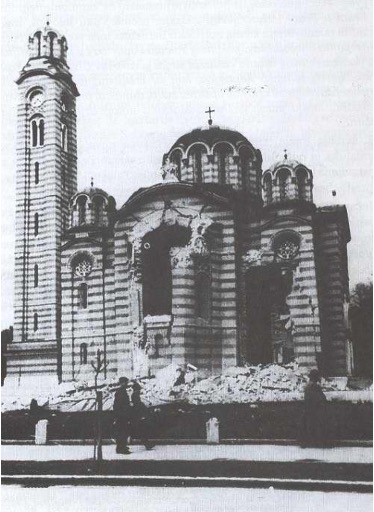

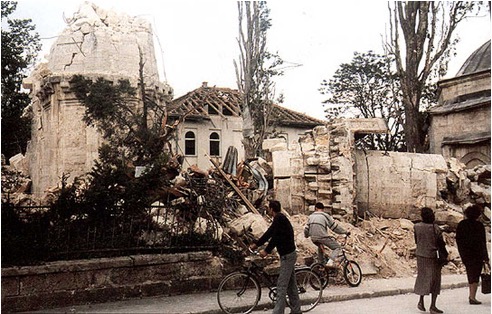

The Ferhadija mosque is central in the blog, but not the only notable religious building in the city. The orthodox church and the mosque have in common that they were not present in the street image for a period of time. The Ustaše (name of Croatian fascists of WWII) destroyed the orthodox church during World War II. Under Tito’s rule in Yugoslavia, it was not rebuilt. The Ferhadija mosque, on the other hand, was present in the cityscape most of the time throughout the 20thcentury. About 50 years after World War II, the Ferhadaija mosque experienced a similar demise as its orthodox counterpart. This time, the Republika Srpska government of Banja Luka during the 1990s wars destroyed the Ferhadija on the 7th of May 1993. For a while, the clocktower (Sahat Kula) was the only part that was left which indicated the previous existence of the mosque in that location. By the end of 1993, also this Ottoman building was levelled and the site was turned into a parking lot shortly after (Walasek 56). Ultimately, it was reconstructed; it reopened in 2016. The orthodox church was rebuilt in 1993, the same year that the Ferhadija was destroyed. The change in government and rise of nationalism quickly created a window of opportunity for the church to be rebuilt, the grounds to be sacralised, and the process of identical reconstruction to start. The pictures below show both buildings in their destroyed and reconstructed state.

Reconstruction processes after conflict

These kinds of changes in the cityscape related to heritage function as indicators of political opinions in the city. The reconstruction processes highlight this even more: these show what is deemed important enough to be reconstructed. This results in these sites acquiring new meanings related to the wars or events that caused their destruction. The process of reconstruction is therefore one of meaning-making and, more importantly, communicating this meaning.

The reconstruction of the Ferhadija did not go off without a hitch. Around 4000 protesters roughly disrupted the laying of the first stone ceremony in addition to political obstructions in the starting phase (2001) (Politika RS; Radio Sarajevo). The (mostly Serbian) protestors threw stones at the Bosniak attendees according to Radio Sarajevo. The mosque was reopened for the public after a reconstruction process of 15 years on the 7th of May 2016. This day became the national ‘Day of the Mosque’ in Bosnia and Herzegovina. It shows how the destruction of the Ferhadija also gives meaning to the destruction of other mosques throughout the country.

The question of representation and the instrumentalization of heritage after conflict

Concluding remarks

Bibliography

Kovačević Danijel. (2017). “Bosnian Muslims Rebuild Historic War-Ruined Mosque.” Balkan Insight. BIRN

Mazzucchelli, Francesco. (2021). “Borders of Memory: Competing Heritages and Fractured Memoryscapes in Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Heritage in the Former Yugoslavia: Synchronous Pasts, edited by Gruia Badescu, Britt Baillie, and Francesco Mazzucchelli. Cham. Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 131-156.

Miklavčić, Alessandra. (2008). “Slogans and Graffiti: Postmemory among Youth in the Italo-Slovenian Borderland.” American Ethnologist. Vol. 35. No. 3. pp. 440–453.

Milan, Chiara. (2020). Social Mobilization Beyond Ethnicity : Civic Activism and Grassroots Movements in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Abingdon, Oxon : Routledge.

Strahl, Tobias. (2021). “Protection of Culture in Conflict: Heritage in a Militarised Environment.” Heritage and Environment. pp. 269-291.

Walasek, H., Carlton, C.B.R., Hadžimuhamedović, A., Perry, V., & Wik, T. (2015). Bosnia and the Destruction of Cultural Heritage (1st ed.). Routledge.

Walasek, Helen. (2019). “Cultural Heritage and Memory after Ethnic Cleansing in post-Conflict Bosnia-Herzegovina.” International Review of the Red Cross. No. 101. pp. 273-294.

About the author

My name is Karlijn Hulshof. I am a student of the MA in Heritage and Memory Studies at the University of Amsterdam. For the past few months, I have been working as an intern for the Ministry of Defense on cultural property protection. I have a background in Slavic studies and learned both Russian and Bosnian/Croatian/Serbian. The area of the former Yugoslavia is one of my main research interests, especially the relationship between heritage, memory, and conflict.

Combining heritage studies with my background in Slavic studies has opened up interesting new angles into both subjects. In line with my interests, the Ferhadija mosque will be one of the case studies in a slightly larger study we carried out on the relationship between heritage and conflict in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Contact Karlijn Hulshof:karlijnjhulshof@gmail.com

Acknowledgments

Karlijn’s Blog is based on the paper she presented during the 23rd International Seminar on Heritage Interpretation and Presentation for Future Generations, held in Amsterdam, The Netherlands on 15th June 2023. The seminar was themed “Understanding Wartime Narratives in the Digital Age” and organised by a partnership including the Seoul National University, Our World Heritage, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam and Heriland.

Check on the “Understanding Wartime Narratives in the Digital Age” conference’s website here.