by Anton Petrukhin

Info Box: History

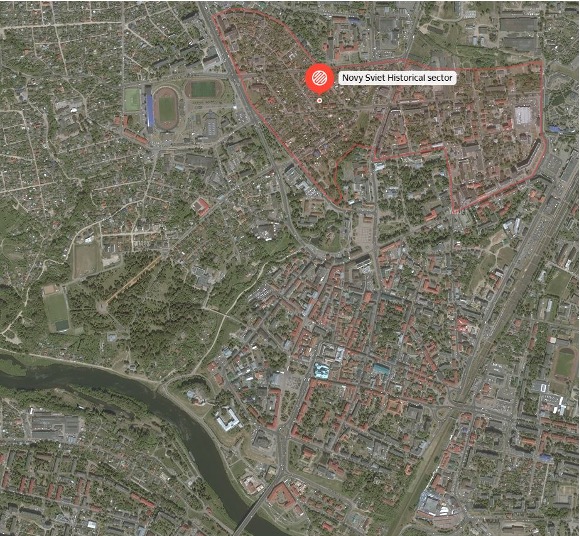

Belarusian Novy Svet (lit. New World) was formed in the second half of the 19th century and became part of Hrodna in 1875. After the Treaty of Riga (1921), when Western Belarus and, accordingly, Hrodna became part of Poland, many more Poles began to live in the Novy Svet area. Meanwhile, it was still defined by its multiculturalism, as Belarusians, Poles, Russians, Jews, Tatars, Ukrainians and Germans lived here together for decades, which certainly reflected the special atmosphere of the place and the variety of architectural styles used by the owners to build their houses. Buildings in Neoclassicism and Zakopane Style (Polish Art Nouveau), Wooden Art Nouveau (Fig. 1), and even Wooden Functionalism (Fig. 2) were erected on a relatively small territory (Казак, Вашкевіч [Kazak, Washkevich], 2008).

About This Blog Series

This is the second blog post of the series of 24 blogs prepared by graduate students and early career professionals who shared their views on the future of heritage and landscape planning.

The writers of these blogposts participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2024 in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Introduction

Urban Renewal is a complex and sometimes controversial concept of the transformation of urban space that, under globalization and neoliberal ideas’ influence, has been moving for decades towards greater inclusion of all stakeholders in urban planning practices and greater attention not only to the physical but also to the cultural, social and environmental aspects of the process.

In this blog post, I would like to talk about a specific case of such transformation of the historic wooden neighborhood Novy Svet in Hrodna (Belarus), which is presented by the gradual disappearance of its elements, both in tangible and intangible form under the pressure of social and political challenges. Moreover, I will try to find out what are the reasons that prevent the preservation of this historic urban landscape. The final chapter of this post will give an inspiring example from Estonia, where despite similar to the Belarusian case unfavorable conditions, the balanced approach was developed to preserve the wooden heritage of the Karlova neighborhood.

A period of stagnation and neglect

In general, the replacement of wooden buildings in European cities with brick ones was a very common phenomenon in the 1960s-1970s. Wooden buildings complexes, traditional for the countries of Eastern and Northern Europe, gradually gave way to areas of new panel construction. This process was triggered by the post-war rural-to-urban migration, which created a widespread demand for new prefabricated housing, as well as by motorization. Gradually the contrast between the preserved areas of wooden buildings and the new high-rise areas became more and more apparent, which affected the attitude change towards wooden architecture (Kalakoski, Huuhka, Koponen, 2020, p.795). Finally, in 1972, during the ICOMOS conference in Sandefjord, Norway, the first Resolution was adopted on “The Wooden Town in Scandinavian Countries” (ICOMOS, 1972). This document made one of the first attempts to identify the problem of preserving existing wooden houses and proposed a change in urban planning policy, paying more attention to the existing urban structure of Scandinavian cities.

In Belarus, which was part of the Soviet Union, there were similar processes of replacing traditional wooden buildings with brick and concrete ones. However, in the absence of significant financial resources, when the main funds were directed to the largest cities (mainly the capital), many reconstruction projects in smaller towns remained on paper. It can be said that the Soviet system even to some extent contributed to the preservation of wooden areas since they were recognized as “rotten” territories, i.e. unpromising and not worthy of reconstruction. Moreover, new construction was favored in the housing sector, and proper building maintenance as a phenomenon was virtually non-existent (Siilivask, 2002, p.5). Thus, the historical appearance of the neighborhoods, and sometimes their interior and exterior decoration remained untouched for decades.

As for Hrodna, its historic center was severely damaged during WWII, but the areas of wooden buildings in the peripheral zone of the city were mostly preserved. Nevertheless, the tradition of construction and, more importantly, caring for wooden buildings was gradually lost, passing into oblivion together with other manifestations of the last century. It is this “non-inclusion”, both in the urban planning and symbolic senses, that for a long time reflected the attitude of the city authorities and citizens towards it as the district that did not deserve special attention and could be sacrificed in the process of reconstruction and creation of the “new socialist city” (Fig. 3).

Renewal or destruction? The uncertain future of the Novy Svet

Talking about the perceptions of the citizens of Hrodna about the Novy Svet neighborhood, I assume that it has not become a real embodiment of the so to say traditional Belarusian urban environment for them. In my private chats with friends (natives of Hrodna), I found out that almost all of them are not familiar with the history of this area. Some of them even have never heard of this “urbanonym” or haven’t visited the area. To my understanding, this can be explained by several reasons.

First, after the annexation of Western Belarus to the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic (BSSR) in 1939, many ethnic Poles and Belarusians of the Catholic faith were forced to move to Poland, as the arrival of Soviet power in the city did not bode well. Many of those who did not dare to leave were deported after some time. (Гумянюк [Humianiuk], 2008, pp.55-56). Later, during WWII, Jewish residents disappeared from the streets of the neighborhood, and not only them. Thus, we can speak of a radical change in the population of Novy Svet in the 1930s-1940s, which also affected the lack of continuity between the old and new residents of the neighborhood.

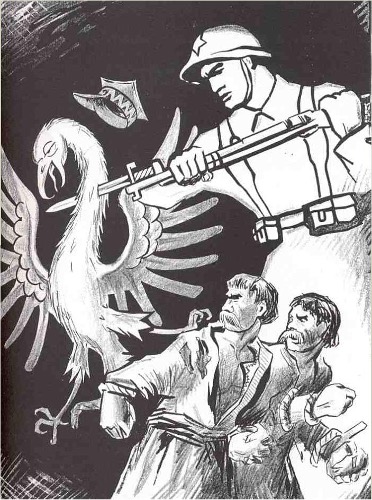

Secondly, in Belarus, the official discourse considers the period from 1921 (the Peace Treaty of Riga) to 1939 quite unambiguously – as the time of discrimination of Belarusians in interwar Poland and the reunification of the BSSR with Western Belarus – as one of the most important events in the modern history of Belarus (Fig. 4). Especially such one-sided views intensified in the state propaganda after 2020 (presidential elections and related protests and repressions) when a significant part of people were forced to flee abroad. The Belarusian authorities have long been looking for a symbol, which, in their opinion, could ideologically unite all Belarusians and emphasize their defiance to the Western countries. As a result, a new state holiday was declared – National Unity Day, which is celebrated on September 17, the day Soviet troops entered pre-war Poland (Fig. 5). Thus, there is no reverence in the Belarusian context for the period before 1939, when the Novy Svet district was mainly formed.

Despite this, local historians and activists have repeatedly tried to draw attention to the problems of Novy Svet. Especially active was the period after 2006, when an integral part of the neighborhood – Zalataja Horka (lit. Golden Mountain) – disappeared forever under bulldozers (Fig. 6). At the same time, a detailed plan for “reconstruction” of the neighborhood was developed by the authorities, which assumed the demolition of more than fifty historical buildings and replacing them with two- or three-storey townhouses. The project was not implemented, but the state’s interest in the radical redevelopment of the area sparked the activity of those interested in preserving the Novy Svet. Thus, over several years, activists published the book “Hrodna’s Novy Svet and Vicinity”, organized art and photo plein airs, collected residents’ memories, and even made a documentary film called “Novy Svet”. The work culminated in the creation of the conceptual project “Hrodna Novy Svet. Prospects for renovation and use”, in which, based on historical sources and similar case studies from around the globe, approaches to the preservation of the unique territory were proposed and the main stages of implementation were highlighted. The document was sent to the Ministry of Culture of the Republic of Belarus, but this did not lead to a change in the situation (Руселік [Ruselik], 2014, pp.42-54). Historic buildings disappear one by one: the last two cases occurred in 2019 and 2022.

Wooden neighborhood Karlova in Tartu (Estonia) as a good example for wooden preservation

Despite drawing attention to the Belarusian case where unfavorable conditions have led to the loss of wooden heritage along with associated intangible aspects, there are positive and inspiring examples from neighboring countries that offer hope for the preservation of the wooden urban heritage of Belarusian cities. For instance, Estonia, which was part of the USSR for decades, shares similarities with Belarus in terms of its contradictory past within the socialist system and its special relation to wooden heritage.

Wooden neighbourhood Karlova in Estonia was built in the 1910s during the “golden age of Tartu’s wooden architecture” (Siilivask, 4 2002, p.2), the houses were characterized by modest exterior decoration in the Art Nouveau style, traditionally called Jugendstil in Estonia (Fig. 7). The interwar period saw the “beautification” of Karlova, as a result of which many of the streets were fitted with greenery including maples, birch trees, poplars and linden trees, which still create the special atmosphere of the neighborhood (Hess, 2011, p.112). As well as its Belarusian counterpart, Karlova neighbourhood in the soviet era experienced decay due to the lack of proper maintenance.

After Estonia gained independence in 1991 and joined the EU, significant reforms led to property returning to former owners, housing system privatization, and the end of new housing subsidies. This resulted in permanent owners in Karlova taking good care of their properties.

Given the high share of the Russian population in Estonian cities, Karlova remained predominantly mono-ethnic Estonian for decades. This was due to Russians (Russian speakers) who moved to Tartu during the Soviet period, settling in new paneled neighborhoods. Thus, even during the socialist period, Karlova retained a strong Estonian identity. This identity continues to attract new residents after independence, evoking a sense of pre-war Estonia and “Estonianness” when the state was not under Soviet influence (Hess, 2011, p.113). This perception by Karlova residents reflects its identification with both material and intangible heritage.

This attitude towards Karlova was formalized in the Tartu Linna Üldplaneering 2030+ (Tartu City Comprehensive Plan 2030+, 2017), where the neighborhood was designated as a milieu protection area. The plan defines the milieu protection area by features such as land plot organization, architectural style, distinctive landscape components, and historical neighborhood formation, i.e., material aspects. Additionally, conditions for new construction and reconstruction were established through cooperation between the municipality and the local community. Kallast (2021, p.917) notes that the document is based on Karlova’s construction history and emphasizes preserving its historical content, specifically the period before Estonia’s Soviet occupation. Therefore, Karlova’s heritage is also viewed in an intangible context, through the tradition of urban landscape organization prior to Estonia’s incorporation into the USSR.

Overall, the collaboration between Karlova residents and city authorities, combined with a special appreciation for wooden architecture as part of the urban landscape and everyday life of authentic (pre-war) Estonia, has contributed to the preservation of the area in both tangible and intangible ways. Notably, the necessary educational infrastructure in Estonia, particularly in Tartu, has been established through long-term cooperation between local architects and their Scandinavian colleagues, who have extensive experience in working with wood. The Restauereimiskeskus (Restoration Center) in Tartu serves a similar educational function on a smaller scale, allowing residents and owners of wooden heritage properties to learn wood maintenance techniques.

Conclusion

The example of Hrodna’s Novy Svet demonstrates a specific approach to urban renewal, where the main type of intervention is the destruction of historical buildings unprofitable through the prism of capitalism and the creation of new complexes without taking into account the citizens’ opinion. The complicated political environment in Belarus does not favor the formation of stable urban communities that could convey their position to the city authorities. Undoubtedly, the Belarusian context is characterized by less reflexivity for political reasons about the country’s period of being part of the Soviet Union, as well as a one-sided view of the annexation of Western Belarus to the BSSR, which, in the context of rethinking the Novy Svet area, deprives it of an important component of historical continuity between the current owners and past residents of the neighborhood.

Despite the loss of wooden heritage and associated intangible aspects in Belarus, there are hopeful examples from neighboring countries. Estonia, which shares a similar past within the socialist system, provides inspiration. Since joining the European Union in the early 2000s, Estonia has undergone extensive reforms in urban planning, moving towards comprehensive urban renewal. Greater involvement of citizens and stakeholders in urban projects has resulted in policies like the collaboration between Tartu’s government and Karlova’s community to preserve Karlova as a milieu protection area. This balanced approach, driven by the residents’ appreciation for Estonian lifestyle and urban landscape, highlights a positive path for heritage preservation.

Bibliography

Hess, D. (2011). Early 20th-century wooden tenement buildings in Estonia: building blocks for neighborhood longevity. Urbanistika ir architektūra. 35(2), pp.110-116. Available at: https://journals.vilniustech.lt/index.php/JAU/article/view/5620/4877. Accessed: 3 January 2025.

ICOMOS (1972). Wooden Town in Scandinavian Countries. Resolution adopted by the Sandefjord Symposium. Available at:

https://www.icomos.org/public/publications/93towns7f.pdf. Accessed: 21 October 2024.

Kalakoski, I., Huuhka, S., Koponen, O. (2020). From obscurity to heritage: Canonisation of the Nordic Wooden Town. International Journal of Heritage Studies. 26:8, pp.790-805. Available at:

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13527258.2019.1693417. Accessed: 20 October 2024.

Kallast, K. (2021). So Close and Yet So Far: The Distant Heritage of the Historical Urban Landscapes of Residential Districts of Tartu, Estonia. Int J Semiot Law 34, pp.907–928. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11196-020-09738-1. Accessed: 19 December 2024.

Restaureerimiskeskus [Restoration Center]. (in Estonian). Available at: https://www.restaureerimiskeskus.ee/et. Accessed: 22 December 2024.

Siilivask, M. (2002). The Historic Town Structures of Tartu – The Historical Overview and Main Preservation Problems Today. Presented at the Workshop on Historic Structures, Advanced Research Initiation Assisting and Developing Networks in Europe. Available at:

https://www.itam.cas.cz/miranda2/export/sitesavcr/utam/ARCCHIP/w11/w11_siilivask.pdf. Accessed: 20 October 2024.

Tartu Linna Üldplaneering 2030+ [Tartu City Comprehensive Plan 2030+] (2017). Tartu Linnavalitsus. Linnaplaneerimise ja maakorralduse osakond [Tartu City Government. Department of Town Planning and Land Management]. (in Estonian). Available at:

https://info.raad.tartu.ee/dhs.nsf/fc7763c017c9f110c22568cd004625d4/3e3cafd0e5700e31c22587c400184dff/$FILE/Tartu%20linna%20%C3%BCldplaneeringu%20seletuskiri.pdf. Accessed: 21 December 2024.

Гродзенскі Новы Свет. Перспектывы рэнавацыі і выкарыстання [Hrodna Novy Svet. Prospects for renovation and use] (2009). (in Belarusian). Available at: https://harodnia.com/images/articles/06/697.pdf. Accessed: 19 October 2024.

Гумянюк, Ю. [Humianiuk, J.] (2008). Прывід даўніх крэсаў (урыўкі з аповесці) [The Ghost of Old Kresy (excerpts from the story)]. Горад святога Губерта. Краязнаўчы альманах [City of Saint Hubert. Local history almanac]. Выпуск IV [Edition IV]. Вільня: Інстытут гістарычных даследаванняў Беларусі ЕГУ [Vilnius: Institute of Historical Studies of Belarus of EHU], pp. 49-68. (in Belarusian). Available at: https://kamunikat.org/?pubid=11224. Accessed: 19 October 2024.

Казак, Т., Вашкевіч, А. [Kazak, T., Vaškievič, A.] (2008). “Новы свет” Горадні [“Novy Svet” of Hrodna]. Горад святога Губерта. Краязнаўчы альманах [City of Saint Hubert. Local history almanac]. Выпуск IV [Edition IV]. Вільня: Інстытут гістарычных даследаванняў Беларусі ЕГУ [Vilnius: Institute of Historical Studies of Belarus of EHU], pp. 5-9. (in Belarusian). Available at: https://kamunikat.org/?pubid=11224. Accessed: 20 October 2024.

Руселік, В. [Rusielik, V.] (2014). Гісторыя руйнаваньня аднаго места. Гістарычная прастора Горадні ў 2008-2013 гг. [History of destruction of one place. The historical space of Hrodna in 2008-2013]. ARCHE Пачатак [ARCHE Beginning]. Мінск: Беларускі дом друку [Minsk: Belarusian publishing house]. Volume 4, pp. 32-72. (in Belarusian).

About the author

Anton Petrukhin is a master’s student in the World Heritage Studies program at the Brandenburg University of Technology, Cottbus, Germany. This Blog post was inspired by his master thesis research with a focus on wooden urban architecture of Belarusian cities, and based on his participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Heritage and Future Landscapes” in Gothenburg, October 2024.

Contact the author: anton.petrukhin.tut@gmail.com