By Samantha Tobiáš

When we think about culture, we think about humankind. When we think about nature, we think about the opposite: something untouched by man. This idea defined the Western heritage understanding for a significant portion of the 20thcentury and before – and played a key role in pioneering the concept of World Heritage. Acknowledging this thinking within the UNESCO system is thus fundamental for heritage and landscape research. Nevertheless, the World Heritage Convention does supply us with the term ‘cultural landscape’, a designation added in 1992. This “combined [work] of nature and of man” (UNESCO 1972 Art. 1) describes a form of cultural heritage site that expresses the relationship between people and the environment – and moreover, it contributes to a paradigm shift.

The heritage field has moved towards the recognition of landscapes as multi-functional domains contributing to agricultural production, socially sustainable livelihoods, and ecosystem conservation. This goes hand in hand with a dynamic understanding of heritage that distances itself from the separation of ‘pristine’ nature and culture, and instead highlights the importance of intangible heritage and people-centred approaches (Smith 2006).

About This Blog Series

This is the third blog post of the series of 24 blogs prepared by graduate students and early career professionals who shared their views on the future of heritage and landscape planning.

The writers of these blogposts participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2024 in Gothenburg, Sweden.

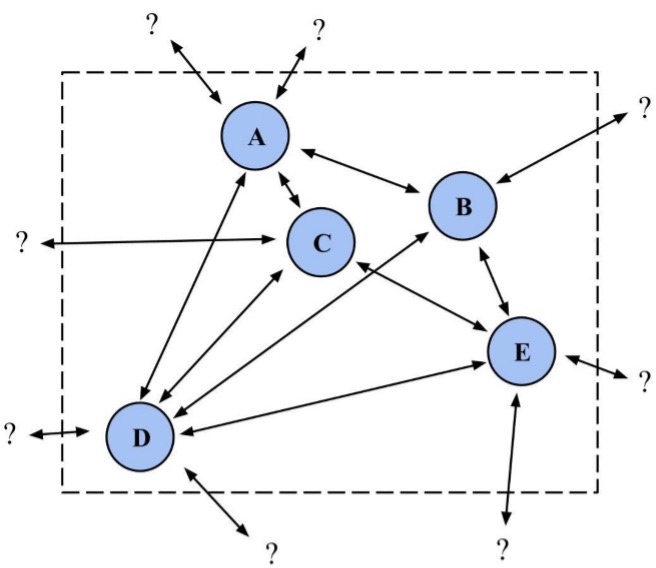

Though social-constructivist and anthropocentric frameworks have practical significance, a possible criticism is the continued prioritisation of humans and separation of the tangible from the intangible. To contribute to moving beyond these limitations, it is worth exploring a posthuman understanding of heritage (Harrison 2013). It is conceptualised as an ‘assemblage’: entangled relationships between the past and present, the object and the practice, across the world and across time, where buildings, landscapes, artefacts, languages, and traditions, as well as individuals and materials, must be regarded dialogically beyond their theoretical function (see Figure 1).

These philosophical ideas are not new, instead following posthuman discourse that aims to decentre the human since the French philosopher Michel Foucault. But a posthuman heritage approach that views landscapes as assemblagesdoes not have to be a far-fetched theoretical exercise. Interdisciplinary landscape research has long understood that different groups place different demands on the landscape, both spatially and temporally, interlinking today’s landscape affordances with the past (Gibson 1979).

One key application of this thinking is climate change: Landscapes around the globe urgently require the implementation of adaptation and mitigation strategies because we understand that all elements of an assemblage rely on each other to upkeep the overall functionality: If one part of the assemblage is harmed, the entire network is harmed (Deleuze & Guattari 1987; Law 2009). With climate change being a complex landscape-scale challenge defined by uncertainty, the lack of one clear solution, and the need for continuous adaptation (Sayer et al. 2013), it affects all aspects of a landscape assemblage.

What does a landscape assemblage look like in practice?

Connemara is a region located on the west coast of Ireland, where the rough Atlantic crashes into rugged cliffs and tidal islets, where winding roads intercept the bog with its freshwater lakes, where black-faced sheep pasture on the rocky slopes of two mountain ranges, and where people work and farm the land, managing the landscape of their ancestors. The assemblage not only consists of fragile ecosystems, renowned for the occurrence of a rare and strictly protected aquatic plant called Slender Naiad, or the eroding dunes that provide habitat for a multitude of birds. An abbey (much visited by tourists these days), Neolithic standing stones, medieval Holy Wells, and a pilgrimage route are contained within the landscape together with afforested timber plantations and the ubiquitous farmland (see Figures 2 to 4).

Connemara’s pastures have often been won from the bog in a hard battle: The high water table makes drainage of the fields an established practice that still leaves the tell-tale moor-grasses behind as indicators of the wet ground and poor soil. But the people persist, as they have for hundreds of years: Wind and rain have shaped the land just as much as humans have, though one manages the land with dry-stone walls that try to keep the heather out and the sheep in; the others have carved and smoothened the metamorphic rock for millions of years. Today, the wind and rain present a challenge to the assemblage, as climate change impacts the way people have been managing the landscape. To illustrate the severity of this, in 2015 eroding sand dunes retreated enough to reveal human remains on a tidal island, necessitating a rescue excavation and additional archaeological recording (Daly 2019:46). But how does posthumanism play a part in this assemblage?

Advocating for a posthuman ontology in heritage management

Going forward, the historically marginalised and rural communities in Connemara will have to face climate change as a challenge to their livelihoods, heritage, practices, and landscape. In viewing these things as interconnected, a posthuman management of the landscape assemblage highlights the people and tangible and intangible heritage attributes and sustainable climate-smart approaches to guide climate adaptation.

To illustrate, a posthuman strategy underlining the role of non-human actors in the landscape might have the potential to contribute to infrastructure maintenance: Today, Connemara’s narrow and winding roads are busy with tourists and local cars. This increase in traffic has led to a once common practice falling out of favour, where livestock used to be moved through the landscape along the roads daily. This practice allowed sheep and cattle to graze on the invasive gorse growing along the roads, thus keeping down the foliage. These days, gorse overgrows and out-competes native vegetation, presenting a fire risk and a hazard to drivers. A return of livestock grazing along roads could potentially mitigate these risks, however, it would also significantly impact the daily comings and goings of people, including the locals.

Hence, careful consideration of advantages and disadvantages for both human and non-human actors is key to providing accessible guidance on how to continuously improve sustainable farming practices. This should take the form of collaborative efforts that are inclusive of the local community and actively involve farmers in decision-making.

In a world where heritage is becoming more and more central to conflict resolution and future-oriented planning in all contexts, enshrining heritage conservation in policy frameworks and the latest research cannot forget to ontologically entangle the human and non-human (Sterling 2020). The perception and communication of potential or occurring issues across all parts of the assemblage can lead to an integrated, holistic heritage approach that flattens hierarchies between various heritage stakeholders and allows for an equitable exploration of both human and non-human elements within the landscape assemblage. We may look beyond the rare Slender Naiad, beyond the dry-stone wall, and view the landscape as a dynamic whole that is capable of transformative change benefitting all actors within its network.

Bibliography

Buitendijk, T., Morris‐Webb, E.S., Hadj‐Hammou, J., Jenkins, S.R. and Crowe, T.P. (2024) Coastal residents’ affective engagement with the natural and constructed environment. People and Nature, 6 (1), 165–179.

Daly, C. (2019) Built & Archaeological Heritage Climate Change Sectoral Adaptation Plan. Project Report. Dublin, Ireland: Department of Culture, Heritage and the Gaeltacht.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (1987) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis, USA: Univ. of Minnesota Press.

Harrison, R. (2013) Heritage: critical approaches. London, UK: Routledge.

Law, J. (2009) Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics. In: Turner, B.S. (ed.). The new Blackwell companion to social theory. Blackwell companions to sociology. Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 141–158.

Sayer, J., Sunderland, T., Ghazoul, J., Pfund, J.-L., Sheil, D., Meijaard, E., Venter, M., Boedhihartono, A.K., Day, M., Garcia, C., Van Oosten, C. and Buck, L.E. (2013) Ten principles for a landscape approach to reconciling agriculture, conservation, and other competing land uses. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110 (21), 8349–8356.

Smith, L. (2006) Uses of heritage. London, UK: Routledge.

Sterling, C. (2020) Critical heritage and the posthumanities: problems and prospects. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 26 (11), 1029–1046.

UNESCO (1972) Convention concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage. Paris, France: UNESCO.

About the author

Samantha Tobiáš is a PhD candidate in World Heritage at the School of Archaeology, University College Dublin, Ireland, researching a landscape-wide, holistic, and voice-integrated Climate Vulnerability methodology for cultural, natural, and intangible heritage. This Blog post is inspired by her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Heritage and Landscapes Futures“ in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024.

Contact: samantha.tobias@ucdconnect.ie