By Kaat Van Son

o bring more attention to heritage landscapes on the fringes of highly developed areas, I present the case of De Ruige Heide in northern Antwerp, Belgium, which I will refer to as the “Rough Moors” from here on. In a fragmented landscape like Belgium’s, the Rough Moors are not an exception; highways, canals, and high voltage cables carve up the landscape, creating divisions that are hard to reverse. The Rough Moors exemplify how such landscapes can lose their connection to varied stakeholders, both human and non-human. By exploring the different historic layers of the Moors, we uncover a deeper understanding of its past. What we consider the “original landscape”, is often more nuanced, and efforts to “give back to nature” may, at times, do more harm than good.

Inspired by Historic Landscape Characterisation, this blog aims to encourage readers to reimagine those neglected and uncomfortable pieces of land that more often frustrate than delight. By focusing on educational solutions, this post seeks to move away from the Authorised Heritage Discourse, encouraging young people to listen to the stories and experiences of different generations and form their own opinions about the spaces they move through daily.

About this blog

This is the 8th blog post of the series of 24 blogs prepared by graduate students and early career professionals who shared their views on the future of heritage and landscape planning.

The writers of these blogposts participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2024 in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Seeing the landscape you grew up in change drastically is always difficult. Abrupt change often evokes a desire to stop progress out of nostalgia, whether it is beneficial or not. As a master’s student in heritage studies, I’m not in a position to deny anyone the right to preserve what they feel attached to. But it’s also my responsibility to critically assess the landscape and communicate my findings to the public, so everyone can have an informed, evidence-based opinion.

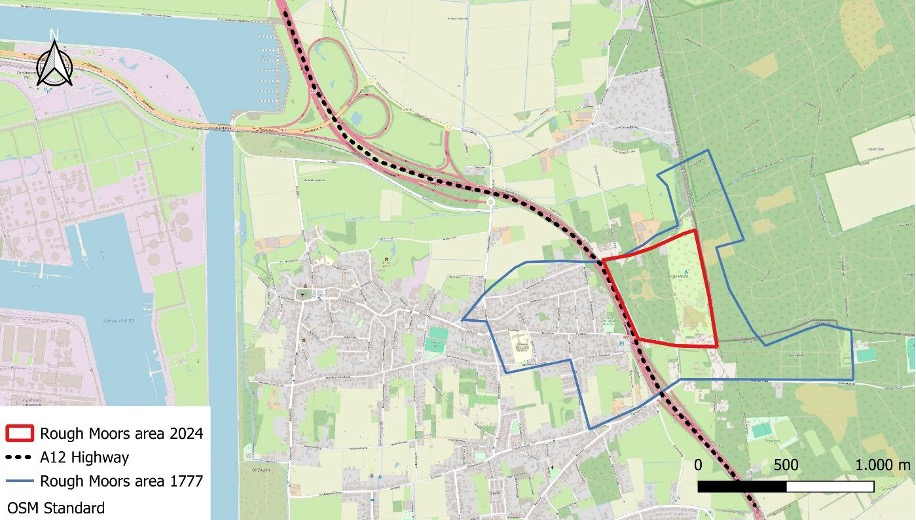

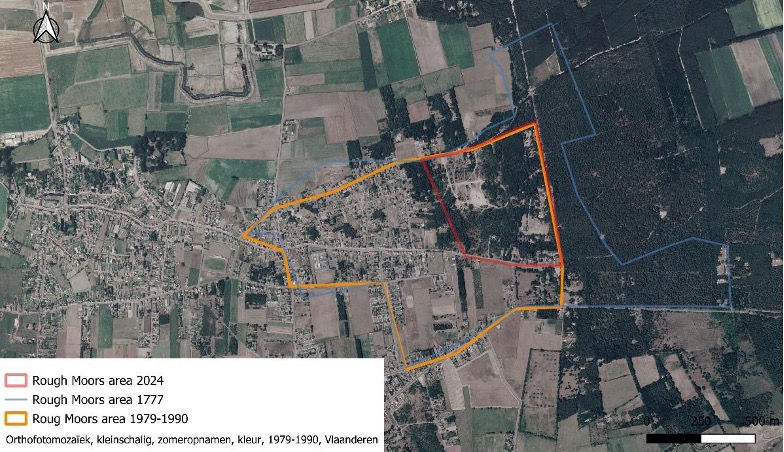

Understanding the Rough Moors requires considering the many elements that contribute to its character. The Historic Landscape Characterisation approach helped me grasp how the current situation came to be and how we might interpret it today. Archaeological excavations dating back to the Roman Empire, alongside studies of fluctuating occupation patterns through the medieval period and Ancien Régime, reveal how the land was used over time. The vegetation that people aim to preserve today is a remnant of intense sod farming, introduced in the 13th century, which stripped the higher parts of this sandy terrain, leaving only the hardiest low-rise vegetation to survive (van den Wittenboer and Venema 2022). The nearby town of Zandvliet became increasingly important as it became one of the most southern fortifications during the Spanish Inquisition, more specifically in the 16th century, which created an everlasting division between the village people in their houses made of brick, and the moor people that had less permanent housing and were poorer (Vrijetijdscentrum De Schelde e.a. 2022). While these activities shaped the land, its borders became increasingly important both politically and economically. On a map from 1777, made for strategic military purposes, we can trace the border of what used to be this heathland that was referred to as ‘Ruygeheide’ – today’s ‘Ruige Heide’ – clearly. In figures three and four, I marked the 18th century border in blue to compare it to the red, the border today (‘Kabinetskaart der Oostenrijkse Nederlanden en het Prinsdom Luik’ 1777).

Though the landscape has changed significantly over time, the most dramatic interventions occurred in the last 40 years (fig. 5). First, a high-voltage network was built across the corner of the Rough Moors, and in 1993, a highway was constructed, connecting Antwerp to Bergen-Op-Zoom in The Netherlands (‘Gewestelijk Ruimtelijk Uitvoeringsplan Hoogspanningslijn Zandvliet-Lillo-Liefkenshoek – Plan-MER. Advies kennisgevingsdossier – Goedkeuring’ 2013). Several houses were demolished, splitting the community of Moor people in two: the western part was absorbed into the village, while the eastern part became increasingly marginalised. With only two tunnels under the highway connecting both sides, people in the eastern part get increasingly disconnected. The restrictions placed on this “natural” area, combined with the constant noise of the highway, caused many residents of the current Rough Moors to move away (fig 4).

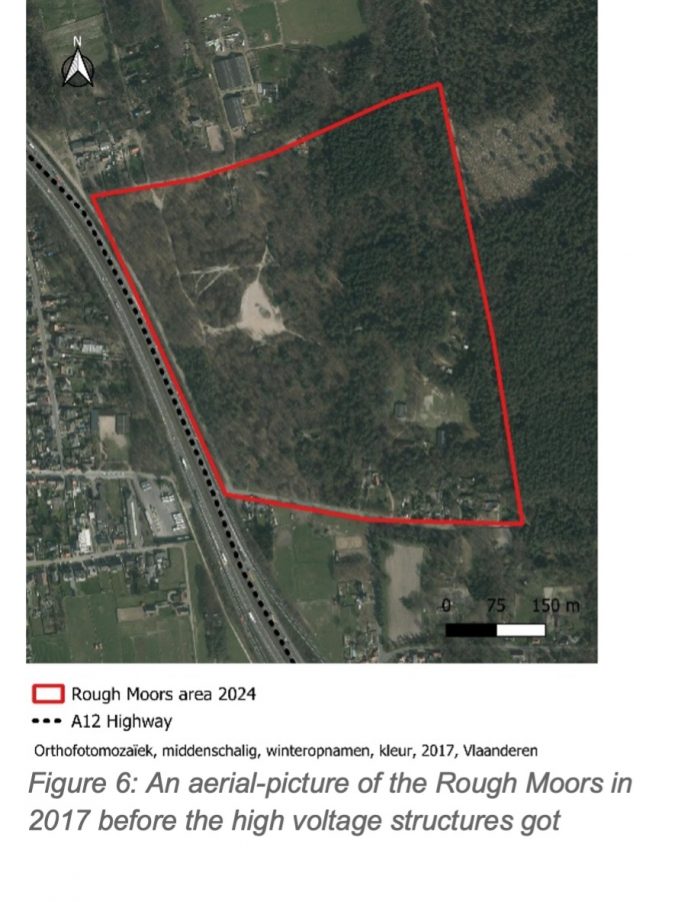

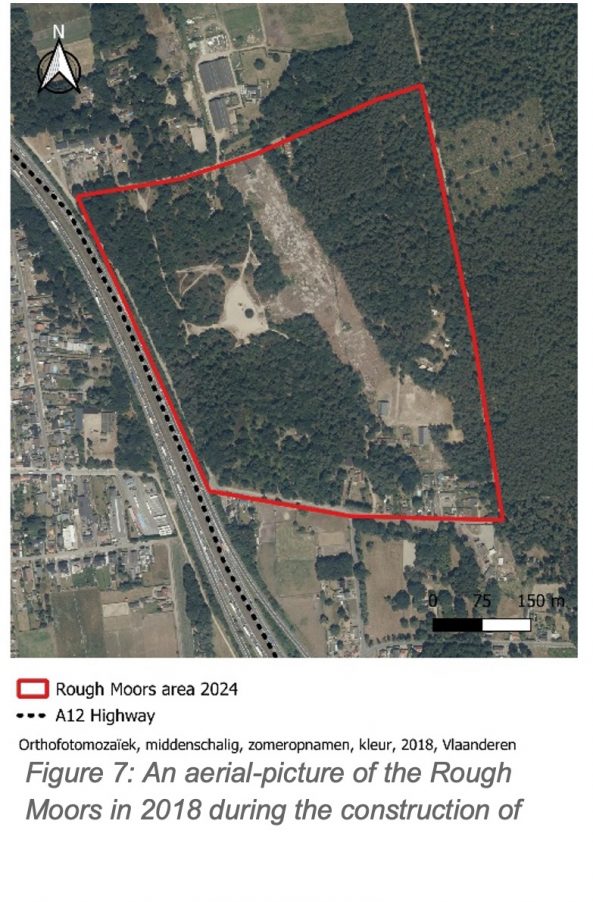

When we analyse all these changes, some issues become visible, mostly when we speak of the consistency of those decisions that were made through time. Proper stakeholder research, like recommended by Historic England, could have led to a deeper understanding of the impact these changes have had over the last 40 years. For instance, the replacement of the high-voltage structures in 2018 could have been better anticipated. All the trees and vegetation were ripped away. The local government called it a win-win because the open landscape is more closely related to what the Rough Moors used to be. But what is left is an uncomfortable strip of land and an interrupted mental image for the people that used to navigate themselves through the moors by the lost pathways, trees and heathlands (‘Ruige Heide | Natuurpunt’ 2024) (fig. 8).

By identifying who uses this area and what it means to them, local authorities could mitigate the loss of experience for its users instead of allowing the local politicians to have an opportunistic bottom-up policy. While we think mostly of human stakeholders, we mustn’t forget the non-human users. When the land is cleared to create a more open, heathland landscape, it might look more authentic. This is a good start if we follow the HLC— but what about the animals that rely on the shelter of denser vegetation? Lastly, we could not call the decision to keep this “open” landscape a true version of Historic Landscape analysis because it is designed poorly. When we look at the publication of Historic England, we understand how historic knowledge specific to this area is used together with a better grasp of how elements in the wider area are connected to this landscape (Herring, Turner and Sevara, 2022.).

Unfortunately, it is too late to fully implement the Historic Landscape Characterisation approach from Historic England, as much of the damage to the Rough Moors has already been done. The highway and high voltage cables have forever altered the landscape, cutting off both the land and its people from their previous connections. However, there is still a way forward (Herring, Turner, and Sevara, 2022.). In a case like this, it is necessary to take a step back from the geo-analysis and the designing table. We never know what the future brings for this landscape as the stakes for modern infrastructure are high. By conducting interviews with the various stakeholders —horseback riders, children who play in the Rough Moors, the youth camps residing during the summer, people who visit for walks, and, crucially, those who (used to) live on this land before it was divided by the highway— we can foster a renewed sense of care for this area. The voices of those former residents are particularly important because they were marginalised by the villagers long before the physical landscape was fragmented. Folklore states that people living on The Moors were looked down upon, as they could not afford to own fertile land and farm on it. Elderly people still joke about how people in this area, shown on the figure with a blue line, are vagrants and ‘marginal’ (fig 10). Their experience of disconnection mirrors the current marginalisation of the Rough Moors itself, creating an intangible but deeply significant layer of heritage that deserves attention (De Vree 1989).

By acknowledging these personal histories alongside the environmental history of the Rough Moors, we can restore not just the landscape, but also the sense of community that has been lost. The Rough Moors could once again become a space where human and non-human lives intersect, where people can come together to enjoy and appreciate this unique, human-made piece of rough nature.

In my opinion, youth have a vital role to play in this process, as they are the most impressionable and as the future of the Moors requires a multigenerational effort. Embedding this project in school programs would allow young people to understand that man-made natural landscapes are the modern reality and that they need to take the lead in reimagining the Rough Moors. By listening to stories from the past and looking forward with creativity, the youth could start looking eye-to-eye early on and maybe one day become a policymaker with a well-considered plan that bridges the gaps —both physical and emotional— left behind during the development of the land. This would turn the Rough Moors into not only a site of heritage, but also an educational and community-driven space.

Bibliography

De Vree, Albert. 1989. Van poldersloot tot wereldhaven : een merkwaardig, meewarig mooi lees- en kijkboek. Antwerpen: Aksis.

‘Gewestelijk ruimtelijk uitvoeringsplan Hoogspanningslijn Zandvliet-Lillo-Liefkenshoek – Plan-MER. Advies kennisgevingsdossier – Goedkeuring’. 2013. Proces Verbaal 141 2013_CBS_00362. Gewestelijk ruimtelijk uitvoeringsplan (GRUP) ’Hoogspanningslijn Lillo – Zandvliet’Ontwerp. Advies/bezwaarschrift. Goedkeuring. Introductie beleidsrichtlijn. Antwerpen: Gemeentebestuur Antwerpen.

Herring, Pete, Sam Turner, and Chris Sevara. 2022. ‘The Historic Landscape: Assessing Opportunity for Change’.

‘Kabinetskaart der Oostenrijkse Nederlanden en het Prinsdom Luik’. 1777. https://www.geopunt.be/shared/b83c375c-b7cf-4372-b693-d1ba506b257f.

‘Ruige Heide | Natuurpunt’. 2024. Ruige Heide. 2024. https://www.natuurpunt.be/natuurgebieden/ruige-heide.

Vrijetijdscentrum De Schelde, Piet Lombaerde, Regionaal Landschap de Voorkempen, and Polderheemkring. 2022. ‘Zandvliet Vestingstad’.

Wittenboer, Shera van den, en Arjen Venema. 2022. ‘Kalmthoutse Heide: Landschapsbiografie en landschapsecologische systeemanalyse’.

About the author

Kaat Van Son is pursuing her master’s in Heritage Studies at the University of Antwerp, where she majors in landscape and natural heritage. She previously graduated from the Vrije Universiteit Brussel with a Bachelor of Arts in Art Sciences and Archaeology. This blog post was inspired by her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Program on “Heritage and Landscapes Futures” in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024.

To contact the author: kaat.vanson@student.uantwerpen.be