Figure 1. Bird’s-eye view of Cologne with MiQua in the foreground and the cathedral in the background.

by Ronja Duwe

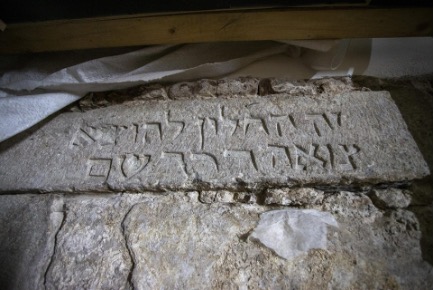

Cologne is a city known for its complex history and cultural diversity. Even the city’s name, derived from Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium, speaks of a long history and Roman past. Today, UNESCO recognises not only Cologne’s material heritage, such as the famous Gothic cathedral, but also the immaterial, including the annual carnival. Building on this rich cultural ground, Via Culturalis is a major city development project, which aims to improve the city and its public spaces through history and culture (“Über Die Via Culturalis,” 2024). MiQua is one of the projects along Via Culturalis’s 800-metre path through the city centre. What started as an archaeological zone in 2007 is expected to open in 2027 as a Jewish museum, showcasing and preserving an expansive landscape of ruins, almost entirely underground. While these ruins include major Roman landmarks and mediaeval workshops, the main goal is to make the 1700-year-old ties between Jews and the city of Cologne visible (“Unser Leitbild,” 2024).

At first glance, MiQua looks like an exciting project, yet after some digging, the picture becomes tainted with criticism and the question: does the project consider Cologne’s citizens? To start, it is expensive. The construction below the streets is complicated and consequently costs more than the average archaeological project. Worse still, through bad luck (or bad planning) the project’s expenses went through the roof. While it was initially predicted to cost 48 million euros, the current estimation is 190 million (“Termin- Und Kostenplan Werden Erneut Fortgeschrieben,” 2024). For reference, the initial cost alone is equivalent to supporting 85 thousand single-households in Germany for a month. As the money comes out of the city’s budget and consequently the taxpayers’ pockets, it is not surprising that local newspapers exclaim their disapproval, wondering if their money is used responsibly and effectively (“Miqua in Köln,” 2021).

About this Blog

This is the 12th blog post of the series of 24 blogs prepared by graduate students and early career professionals who shared their views on the future of heritage and landscape planning.

The writers of these blogposts participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2024 in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Another criticism is that the ruins will be turned into a museum with an entrance fee which guarantees the exclusion of some, perhaps even many. In contrast to the city’s master plan, aiming for inclusion, the museum might create boundaries and social division (“Die Stadtstrategie,” 2024). Barbara Bender argues that turning a landscape into a museum brings with it the image of a place frozen in time. An active and lived-in place becomes seemingly static, a false and manipulative image (Bender, 1993). However, while Bender’s example, Stonehenge, had been used and appropriated prior to being turned into a museum, Cologne’s ruins would not have been accessible to anyone without the city’s intervention. Would Bender thus make an exception here? Incidentally, MiQua advertises itself as a learning ground because of its partnership with a local Gymnasium. The students at this type of school, the highest level of highschool in Germany, tend to come from socially and economically well-positioned families. Instead of aggravating the existing inequalities and elitism, perhaps MiQua could use this opportunity to level the playing field by opening up the space as a learning ground for all students?

The practice of selective storytelling and highlighting of particular cultures, which is common in museums, is another issue (Bender, 1993). As pointed out by Colin Renfrew and Paul Bahn, any interpretation and presentation of heritage is inherently linked to subjective feelings, opinions, and goals of those telling the story (Renfrew, and Bahn, 2016). MiQua is a project driven by the Authorised Heritage Discourse. Those who tell the story are ‘the experts’: historians, archaeologists, and the government. They decide on a version of the story which they deem correct and/or beneficial. In the process, alternative versions of the story are buried. As Doreen Massey states, “places do not have single, unique ‘identities’; they are full of internal conflicts” (Massey, 1994). So, those who do not associate with the portrayed, simplified story might feel alienated from the place and society they live in. How does this fit the city’s goal of making every citizen feel at home? This is not to say that minorities (e.g. Jews, in the case of MiQua) should be suppressed to please the majority. On the contrary, I believe that showing and fostering the diversity of cultures is key. But can MiQua achieve this in its current form?

The last area of criticism is related to MiQua’s apparent prioritisation of tangible over intangible heritage. Over recent years cultural tourism, mostly chasing tangible heritage, has become increasingly popular, which led to many (cultural) landscapes becoming overcrowded and ultimately suffering (West, and Ndlovu, 2010). That is why, today, many heritage experts are opting for slow tourism or entirely different ways of boosting the economy. Yet, in Cologne, attracting tourists appears to still be a major goal. Why? Besides, the idea that material culture contributes to a sense of home is being contested by various scholars. Instead, many believe that it is the intangible which defines our identity and meaning of home (Gimeno Martínez, 2016). So, if that is true, rather than “museumizing” the past, should we not focus on the sharing of intangible heritage? Several local bottom-up initiatives are doing exactly that: connecting people and cultures through shared activities, such as cooking, see Fig.5 (“Familien Kochen Und Vernetzen,” 2024). While these initiatives, with their focus on living heritage, appear to stand in stark contrast to traditional museums, maybe MiQua can still bridge the gap and become an active contributor to the community.

It is clear that the situation has as many layers as Cologne’s landscape. Despite the criticisms, one could argue that the troubling past of Jews in Germany is a common concern and justifies spending a fortune on commemorating their connection to Cologne. After all, it might contribute to a feeling of unity and empathy. In the current political situation, including the war in the Middle-East, the complexity of the project has increased even further. Any decision with regards to the project might be interpreted as a political move. And maybe for good reason…? While personally I am curious to visit the museum, I can’t help but wonder if this project was the best choice from the citizens’ point of view. But, considering the project is not yet completed, there are still opportunities for making it more inclusive. This case demonstrated that by digging up the past one might not only find treasures but also kick up dirt.

Bibliography

Bender, Barbara. “Stonehenge: Contested Landscapes.” In Landscape: Politics and Perspectives, edited by Barbara Bender, pp. 245-79. Providence: Berg, 1993.

“Die Stadtstrategie “Kölner Perspektiven2030+”.” Stadt Köln, accessed October 22, 2024, https://www.stadt-koeln.de/artikel/68263/index.html.

“Familien Kochen Und Vernetzen.” Wir im Nordquartier e. V., accessed October 22, 2024, https://www.wir-im-nordquartier.de.

Gimeno Martínez, Javier. Design and National Identity. London: Bloomsbury Academic, an imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, 2016.

Massey, Doreen B. Space, Place, and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5749/j.cttttw2z.

“Miqua in Köln: Noch Später, Noch Teurer.” Bund der Steuerzahler Nordrhein-Westfalen e. V., Updated August 14, 2021, https://steuerzahler.de/newsundservice/news/miqua-in-koeln-noch-spaeter-noch-teurer/?L=0&cHash=22224ecf320aebf369f916b482a77b60.

Renfrew, Colin, and Paul G. Bahn. Archaeology : Theories, Methods, and Practice. Seventh edition revised & updated ed. London: Thames & Hudson, 2016.

“Termin- Und Kostenplan Werden Erneut Fortgeschrieben.” MiQua – Museum im Quartier, Stadt Köln – Amt für Presse- und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit, updated June 21, 2024, https://www.stadt-koeln.de/politik-und-verwaltung/presse/mitteilungen/26834/index.html.

“Unser Leitbild.” MiQua, accessed October 22, 2024, https://miqua.lvr.de/de/das_museum/unser_leitbild/unser_leitbild_1.html.

West, Susie, and Sabelo Ndlovu. “Heritage, Landscape and Memory.” In Understanding Heritage and Memory by Tim Benton, and Open University. Manchester UP: Manchester (Understanding global heritage), 2010.

“Über Die Via Culturalis.” accessed October 22, 2024, https://www.viaculturalis.cologne/.

About the Author

Ronja Duwe is a designer and researcher based in the Netherlands, who recently graduated from the master’s Design Cultures at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. This Blog post was inspired by discussions on citizen participation and the layers of landscapes during the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Heritage and Landscapes Futures” in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024.

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ronja-duwe-86184010b