by Irene Fogarty

I visited Artis Zoo in October 2022 as part of Heriland’s intensive course, “Cultural Heritage and Planning of European Landscapes”, to learn about interlinked and layered elements of Amsterdam’s urban landscape – in this case, the relationship between Artis Zoo’s values and the maritime heritage of Amsterdam. During a week of intensive learning on-site in Amsterdam, we were introduced to the Historic Urban Landscape approach (HUL). HUL sets out to guide heritage resource management in changing urban environments by identifying layered and interconnected elements of landscapes including nature-culture interlinkages, tangible and intangible values, and international- to local-scale values that can diversify across cultures and communities[1]. In addition to providing a framework for a substantive view of urban landscapes, HUL also calls us to account for social and economic challenges and the need for sustainable futures in heritage conservation[2].

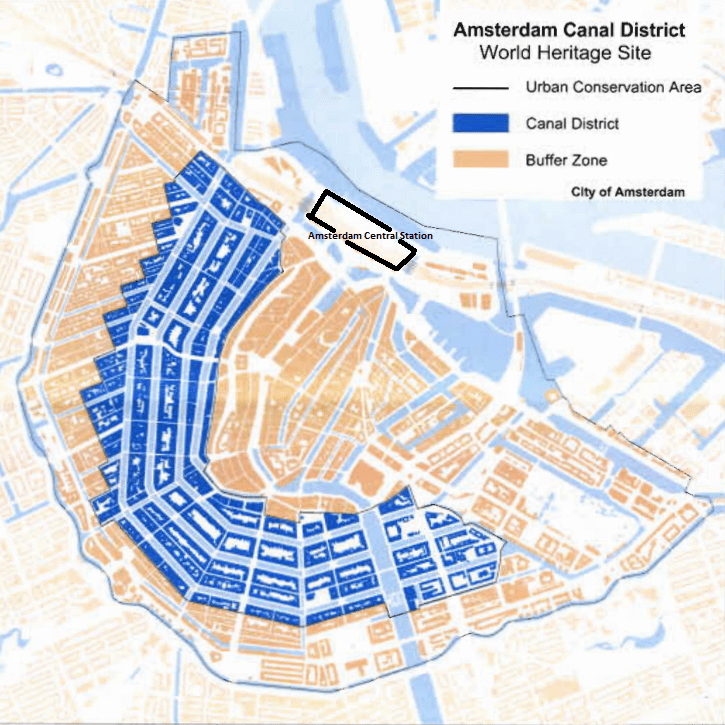

As urban landscapes need to be understood as extending “beyond the notion of ‘historic centre’ or ‘ensemble’ to include the broader urban context and its geographical setting”[3], I felt the principles of HUL would be useful in understanding how Artis Zoo’s values are linked to those of the World Heritage-inscribed Seventeenth-Century Canal Ring Area of Amsterdam inside the Singelgracht. Artis Zoo lies in the World Heritage buffer zone[4] and the incongruity of its species collection – including apex predators like the Arctic Wolf – in a distinctly urban and spatially limited setting had also struck me. I felt a critical examination of the zoo and its cultural and environmental contexts to be a timely and important exercise. Some zoos are linked to colonial narratives and the subjugation of the “Other”, where captivity of animals mirrored the domination of nature and peoples by colonial empires[5]. Conversely,, zoos are increasingly vital in supporting public education, ex-situ conservation and captive breeding programmes in the midst of the biodiversity and climate crises. Is Artis Zoo in its current form an exercise in conservation or coloniality – the invisible but constitutive side of modernity that surpasses boundaries of colonial administrations, reproducing uneven power relations and domination of Eurocentric knowledge production?[6]

Amsterdam’s World Heritage boundaries, with position of Artis Zoo visible at red arrow.

Image/Abrahamse, Kosian and Schmitz (2010)

In its World Heritage evaluation of the urban ensemble of Amsterdam, ICOMOS asserts how the city, especially in the Seventeenth Century, was “an extraordinary intellectual, artistic, and cultural crucible, at the heart of the definition of the values of the modern European world”[7], values which included rationalisation of nature and pursuit of science knowledge. The origins of Artis Zoo are an ideological and spatial continuation of these “modern” values. Founded by wealthy burghers in 1838, Artis was the first modern zoo in continental Europe and an important centre for natural history research in the Nineteenth Century[8]. It also functioned as a private members’ club, hosting zoological talks and concerts and serving an important role in creating and reproducing Dutch nineteenth-century bourgeois culture.[9] However, as Walter Mignolo states, there is no modernity without coloniality[10] and these intellectual pursuits were rooted in Eurocentric academic scholarship that paralleled colonialism. For example, Anthropology as an early scholarly discipline reflected the need for colonial societies to legitimise racial and cultural differences between the colonial metropole and colonised.[11] Throughout modernity, the scientific method dominated Western academia as a way of knowing, relegating Indigenous knowledge systems and forging a division between nature and culture within conservation practice which extended to zoos. Maneesha Deckha describes how zoos never moved away from a colonial ideology of “species-thinking” which reinforces “Man’s” human exceptionality and mastery over nature[12]. Zoos served to distinguish the colonial metropole from colonised territories, where humans and the city stood in “civilised” contrast to savagery[13].

Zoological library constructed in 1867 at Artis Zoo.

Photograph/author’s own

Despite this cultural and ideological legacy, Artis Zoo demonstrates a move towards more holistic understandings of nature-human interlinkages, primarily through the recently renovated Artis Groote Museum. Here, visitors are encouraged to explore the connection between themselves and “all other life in the world”[14]. For example, live talks in January 2023 included how to connect with and listen to nature[15]. The museum’s mission stands in contrast with the zoo’s self-acknowledged colonial history which asserted an Othering of non-Western peoples, portraying them as part of nature to be studied by “civilised” society.[16] Furthermore, the zoo has implemented some successful ex-situ conservation programmes for endangered species and their reintroduction to the wild, including Griffon vultures bred for release in Sardinia[17]. This aligns with UNESCO’s HUL recommendation which cites the need to integrate cultural and natural resources for sustainable development[18].

Griffon vultures, successfully bred in captivity.

Photo/Artis Zoo website

Arguably, however, the zoo’s many antiquated animal enclosures reflect species thinking and rationalisation of nature in addition to reflecting financial and spatial constraints. It must be acknowledged that Artis Zoo’s urban location limits expansion, while its charitable status means the zoo is primarily dependent on memberships and day visitors for revenue[19].

That said, while observing many antiquated enclosures, I related to Natasha Silva’s description of visitors’ conflicting emotions at zoos, involving “awe and respect for animal subjects, but also guilt, anger and sadness reflecting their confinement for human pleasure”.[20] These emotions prompted deeper questioning on the zoo’s purpose in keeping animals like the Arctic Wolf in captivity. The immediate point of information is the enclosure’s interpretive panel, yet this panel failed to cite the animals’ IUCN Red List status or the zoo’s conservation role therein. The Arctic wolf is, in fact, an IUCN Red List species of “Least Concern”[21]. If kept captive for educational purposes, I argue this reproduces coloniality of knowledge, where Eurocentric separation of the self from nature legitimises knowledge gained through spectacle of the Other in “civilised” surroundings.

Interpretive panel lacking information on Arctic wolves’ conservation status.

Photo/Author’s own

While historic urban areas are, according to UNESCO’s HUL recommendation, a key testimony to humankind’s endeavours and aspirations through space and time [22], values are never static. Although Groote Museum reflects a shift from Artis Zoo’s colonial narratives towards recognition of human-nature interlinkages, we are obliged to reckon with difficult, contradictory values the zoo represents. While acknowledging the constraints for expansion

and improvement externally imposed upon Artis Zoo, I argue that its captivity of some animals is still problematic, elevating species-thinking and asserting Eurocentric ways of knowing as acceptable forms of dominance over our more-than-human relations.

[1] See http://www.historicurbanlandscape.com/

[2] UNESCO (2011) Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape [online] https://whc.unesco.org/uploads/activities/documents/activity-638-98.pdf Last accessed January 11, 2023

[3] UNESCO (2011) Op. Cit. p. 3

[4] Abrahamse, J.E., Kosian, M. & Schmitz, Erik (2010) Urban Economics Urban Development, Land Use and the Real Estate Market in Early Modern Amsterdam. In: W. Börner, S. Uhlirz & L. Dollhofer (eds.), Proceedings of the 15th Vienna Conference on Heritage and New Technology. 163-186.

[5] Mehos, D.C. (2006) Science and Culture for Members Only – the Amsterdam Zoo Artis in the Nineteenth

Century. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press

[6] Quijano, A. (2007) Coloniality and modernity/rationality. Cultural Studies, 21(2–3), pp. 168–178.

[7] UNESCO (2010) ICOMOS Advisory Body Evaluation. [Online] https://whc.unesco.org/document/152438 p.264 Last accessed January 11, 2023

[8] Mehos, D.C. (1997) Science Displayed: Nation and Nature at the Amsterdam Zoo Artis. Unpublished Thesis [online] https://www.proquest.com/docview/304365976?pq-

origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true Last accessed January 11, 2023

[9] Mehos, D.C. (2006) Op. Cit.

[10] Mignolo, W. (2011) Introduction: Coloniality, The Darker Side of Western Modernity. In: Mignolo, W. The Darker Side of Western Modernity. Global Futures, Decolonial Options. Durham: & London: Duke University Press, p.3

[11] Harrison, R. and Hughes, L. (2009) Heritage, Colonialism and Postcolonialism. In: Harrison, R. (Ed.) Understanding the Politics of Heritage. Manchester, New York: Manchester University Press, p.238

[12] Gilich, Y. (2020) ‘This is not a pig’: Settler innocence and visuality of zoos. Image and Text, No. 34, 2020, p.4.

[13] Deckha, M. (2012) Toward a Postcolonial, Posthumanist Feminist Theory: Centralizing Race and Culture in Feminist Work on Nonhuman Animals. Hypatia, Vol. 27, No. 3, Special issue: Animal Others (Summer 2012), p. 540

[14] Artis Groote Museum (2023) Discover. [Online] https://www.grootemuseum.nl/nl/ontdek Last accessed January 11, 2023

[15] Artis Groote Museum (2023) Agenda [Online] https://www.grootemuseum.nl/nl/agenda Last accessed January 11, 2023

[16] Artis Groote Museum (2023) History [Online] https://www.grootemuseum.nl/en/history Last accessed January 11, 2023

[17] Artis Zoo (n.d.) Nature Conservation [online https://www.artis.nl/en/discover/nature-conservation/nature-conservation-project-griffon-vulture/ Last accessed January 11, 2023

[18] UNESCO (2011) Op. Cit. p.4

[19] Artis Zoo (2021) Jaarverslag 2021 [Online] https://www.artis.nl/media/filer_public/21/c7/21c74b77-19d4-4222-9162-ff6956c8cc1b/jaarverslag_artis_2021_def_highres.pdf Last accessed January 11, 2023

[20] Silva, N. (2004) Paradise in the Making at Artis Zoo, Amsterdam. In: Bouquet, M. and Porto, N. (Eds) Science,

Magic and Religion, the Ritual Processes of Museum Magic. New York and Oxford: Berghahn Books, p.120

[21] WWF (2022) Arctic Wolf Facts. [Online] https://www.worldwildlife.org/species/arctic-wolf Last accessed January 11, 2023

[22] UNESCO (2011) Op. Cit. p.1

About the author

Irene Fogarty is a PhD Scholar at the University College Dublin, Ireland. This Blog post is based on her PhD research as well as her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme in “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”. Her PhD research on Indigenous Peoples and Protected Areas in Canada is funded by the Irish Research Council-Government of Ireland Postgraduate Scholarship & National University of Ireland’s Travelling Doctoral Studentship.

Contact Irene: irene.fogarty@ucdconnect.ie

About the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”?

Contact Niels van Manen: n.van.manen@vu.nl.