By Maitri Dore

Note: All photos by the author unless otherwise specified.

In a remote town on the border of Karnataka and Telangana in southern India lie a clutch of mostly unsung 15th-17th century monuments. Bidar is the erstwhile seat of the Muslim rulers of southern India – the Bahamanis, followed by the Barid Shahi dynasty – and many of the monuments that exist in the town today are from the time that Bidar was a seat of Deccan power.

In February 2021, between coronavirus waves, I had the opportunity to visit with a friend, and in the 36 hours we spent there, see up close how legislation for preservation reflects in the management (or lack thereof) of monuments tagged as heritage.

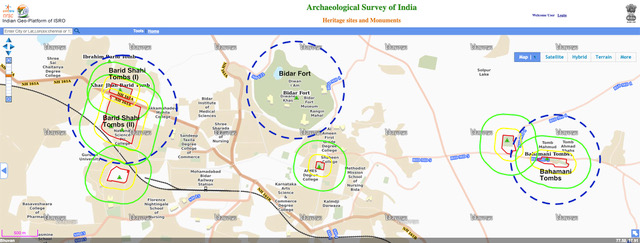

Source: Indian Geo-Platform of ISRO, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)

We visited the Barid Shahi Tombs (I), located in Barid Shahi Park; Barid Shahi Tombs (II), in Memorial Park; Bidar Fort; and Bahamani Tombs, all designated as nationally important monuments[1] by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), the central heritage protection body under the Indian government’s Ministry of Culture. The legislation is premised on the sanctity of built fabric and rings of protection surround these structures: new construction is prohibited up to a 100-metre radius and regulated up to a further 200 metres. What was curious, was that despite being governed by the same protective legislation, in reality there was a range of results in terms of how different monuments were fussed over or forsaken.

Rigid control

Take for example, the rigid control of the Barid Shahi Tombs (I). On paying the entrance fee and entering during the designated opening hours, we emerged into a perfectly manicured attempted utopia. The blocky tombs sat in a landscape composed of cropped grass and sculpted topiaries. Every attempt had been made to regulate the environment, be it through the cordoning off of the structures, the signs banning use around them, or the deliberate, choreographed lighting.

Another, less micro-managed, attempt at paying obeisance to the structure was seen in the Bidar Fort complex. A sign implored the public to “keep [the] monument neat and clean” and refrain from eating in its bowels. Lingering was strictly prohibited, with a security guard routinely rounding up offenders who sat on the plinth of one of the structures. Five minutes only, we were warned, lest we desecrate it. Further, in a more radical homage to the architecture of the fort, a new structure housing toilets had been built on the premises: in the image of the old, its arches and brickwork invoked the design elements of centuries past.

Inaction and takeover by the elements

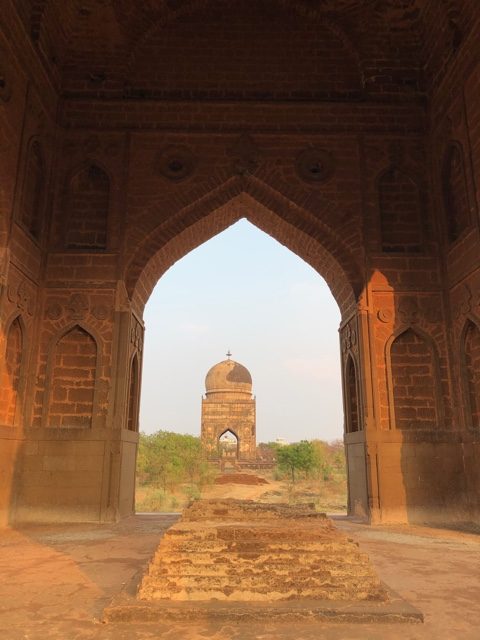

These forms of deference to the monuments and their materiality lay in stark contrast to some other treatment meted out to similarly heritage-tagged structures in the town. The Bahamani Tombs occupied a vast open ground on the outskirts of Bidar. Here, a string of mausoleums was found in various stages of neglect: the onion-shaped dome of one had all but imploded, weeds mushroomed out of others, and graffiti adorned the walls. There was no visible surveillance of the area and no one to prevent us from spending a good half an hour sheltering from the sun in one of the monuments’ 500-year-old laterite brick niches.

A passive takeover by nature was also found in Memorial Park, home to the pair of Barid Shahi Tombs (II). Accessed through thickets of scrub and a long mud path, the individual structures were strewn across a clearing in the centre of dense shrubbery, and connected by criss-crossing dirt paths. There was no curation here, only the perfunctory signboard declaring the monuments as nationally important and a blink-and-you-miss-him security guard patrolling the area. The density of vegetation, and desertedness at the heart of the premises even prompted a pair of well-meaning vigilantes to hustle us out as dusk fell, citing safety concerns. Closer to the road and at the periphery of the site, the park had more quotidian uses like playing cricket. This complex was an example of minimal management, and maximum space for potential public activity, even though some of it could be unsavoury.

Photo: Reetika Revathy Subramanian

Preservation with a twist

The preservation laws governing all these monuments rest on the notion of material supremacy. The monuments’ truth lies in their wholeness: accordingly, “whoever destroys, removes, injures, alters, defaces, imperils or misuse[s] [the] monument” will be slapped with criminal charges[2]. By the yardstick of immaculate wholeness, the Barid Shahi Tombs (I) and the Bidar Fort complex seemed to reflect the authorities’ aspirational models for preservation.

Possibly due to stretched resources or other constraints, similar treatment was not accorded the Bahamani Tombs and Barid Shahi Tombs (II). These inadvertent ruins, not to be confused with the fashionable ones of adaptive reuse or the enlightened ones of curated decay[3] encouraged a variety of processes – human and ecological – to flourish in the cracks (or gaping holes) of state control. From a legislative point of view the ruins and their surrounds may have presented like failed preservation attempts, but in fact, they were charged with potential. Though unintended, the possibility to lounge, to play cricket, to stomp through tall grass, all in the mighty presence of centuries-old architecture seemed to offer a new and liberating paradigm for managing historical sites. Remove the threat to one’s person, add a dash of management and a lot of freedom of use, and we could be staring at the future of preservation. It may not have been what the ASI had in mind, but the ruins of Bidar may be on to something.

[1] The information is based the ASI’s geo platform https://bhuvan-app1.nrsc.gov.in/culture_monuments/ accessed from the National Monuments Authority (NMA) website. The NMA manages the prohibited and regulated areas around centrally protected monuments.

[2] Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act (AMASR Act) of 1958 (amended 2010)

[3] DeSilvey, C. (2017) Curated Decay: Heritage beyond saving. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.