By Ismael Pharoun

Back in 2015, in my first academic year on my way to the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem, I would regularly pass by Hillel Street, Agron Street (Ma’man Allah Street) and King George Street. These are central and well-known streets in Jerusalem. I would pass by them without noticing what lies between those three streets. One day I noticed a tomb, and curiosity led me into a cemetery I did not know existed. The graves and tombs were obviously decorated with Islamic writings. On that day I realized its existence. Although it is in a central area in the heart of the city, there was no information about the cemetery. In fact, the infrastructure, such as the declared Park of Independence by the Israeli occupation and the many buildings surrounding the cemetery made it nearly unnoticeable, especially for people driving their scooters or cars, but even for people walking by.

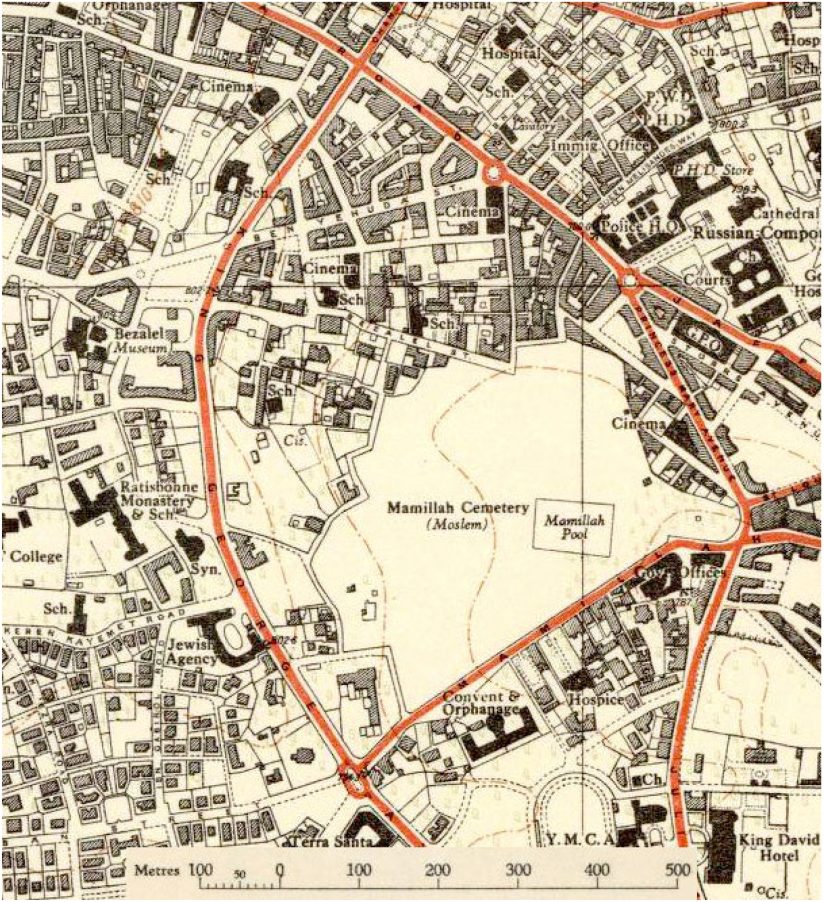

Figure 1. The “Mamillah” district of Jerusalem in 1946, including the “Mamilla Cemetery (Moslem)” and the “Mamilla Pool”. Survey of Palestine (a department of the British mandatory authorities in Palestine) – Part of sheet 2 of the map series “JERUSALEM 1:10,000” compiled and drawn by the Survey of Palestine, 1946.

Figure 2. A screenshot of the site today taken from Arcgis.com – 2022, Maxar | KADDB, RJGC, Esri, HERE, Garmin, Foursquare, METI/NASA, USGS.

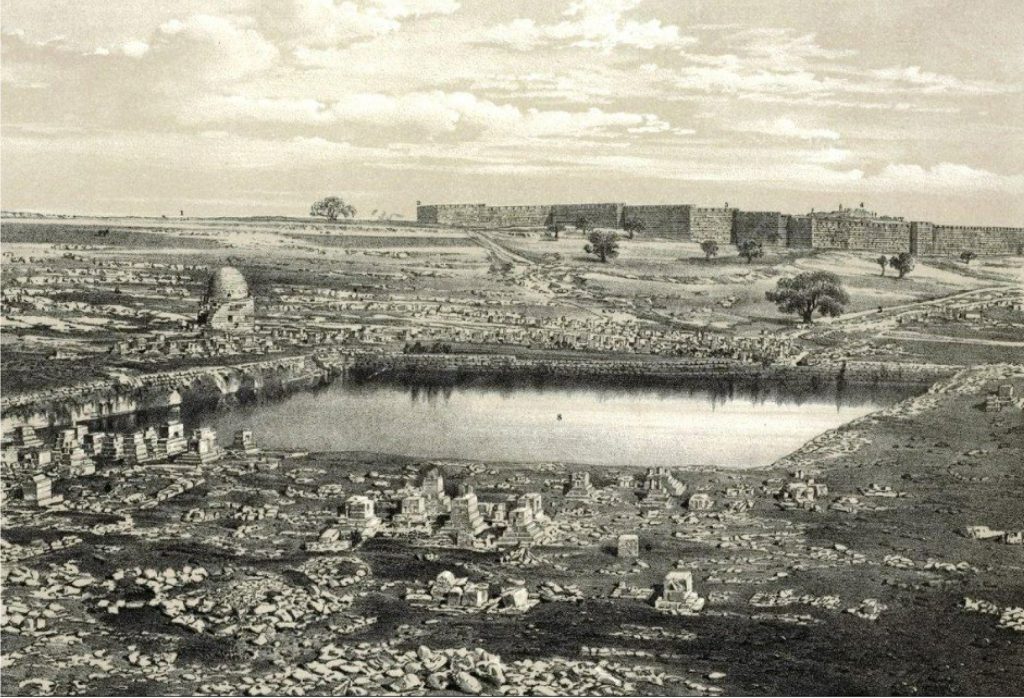

The graveyard is a historical Muslim cemetery in West Jerusalem, just to the west of the northwest corner of the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem, near Jaffa Gate and the New Gate. The cemetery grounds also contain the bodies of thousands of Christians killed in the pre-Islamic era, as well as several tombs from the time of the Crusades. It was used as a burial site for over 1,000 years until 1927 when the Supreme Muslim Council preserved it as a historic site.

In 1948, the Israeli Ministry of Religious Affairs stated that the cemetery is: “one of the most prominent Muslim cemeteries, where seventy thousand Muslim warriors of [Saladin’s] armies are interred along with many Muslim scholars […] Israel will always know to protect and respect this site”.

Unfortunately, the authorities did not live up to those words. Today, it seems like they actively want to erase it. Recently, Municipal Israeli authorities authorized the building of a museum on the grounds of the Ma’man Allah cemetery. Ironically, the museum is called “the Museum of Tolerance”. Beyond the lofty words, the museum aims to rewrite the history of the cemetery – taking more of its land and erasing indigenous Palestinian Arab heritage.

During the Heriland course on Cultural Heritage and Spatial Planning, in 2022 in Amsterdam, I was introduced to two approaches for understanding and managing cultural landscapes: Historic Urban Landscape (HUL), and Historic landscape characterization (HLC). In the HUL training session, we were introduced to strategies that allow the preservation of heritage in the network of nowadays growing cities; the HLC workshop gave us tools which focused on enriching our maps by enabling us to characterize elements and categorize them to better understand the area. Furthermore, I participated in seminars on spatial change and changing demographics.

During the course, we also got the opportunity to do a fieldwork assignment; my group and I chose to go to the recently opened National Holocaust Memorial, “Namen Monument”, in the former Jewish neighbourhood of Amsterdam. The monument was designed by the internationally renowned architect, Libeskind. Ironically, the same architect also designed the Museum of Tolerance on the Ma’mn Allah Cemetery in Jerusalem, (even though other architects, such as Frank Gehry, the Pritzker prize winner, refused to design the museum for ethical reasons).

My group and I asked the visitors about their opinions and feelings while entering the site. Everyone praised the idea of the monument and said it was vital to keep alive the memory of the victims and deaths. An old lady who lives nearby remarked that she volunteered to help build the monument brick by brick.

During their occupation of the Netherlands, the Nazis killed over 100 thousand Dutch Jews; more than two-thirds of the Jewish population in The Netherlands.

I do believe that graveyards like monuments can withstand the passage of time – unless they are actively erased. In an interview with the Centre for Constitutional Rights, Dyala Husseini Dajani, a Jerusalemite whose ancestors are buried in the cemetery and who had joined a petition to the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights to halt the desecration, said:

“The systematic desecration of our ancestors’ resting place and destruction of our cultural heritage by Israeli authorities confirms our feelings that Israel has no regard for the human rights of living Palestinians, or the peace of the dead. We are under no illusions that we are anything but third-class citizens in the eyes of the Israeli state, which treats us and our history with utter contempt, while the international community stands silently by […]”.

Figure 3. POOL OF MAMILLAH, OR SERPENTS’ POOL (ACCORDING TO JOSEPHUS), NEAR THE MONUMENT OF HEROD ON THE WEST OF THE CITY., E. Pierotti, Photo. & Delt—E. Walker, Lith. Cambridge. Deighton, Bell & Co—London. Bell & Daldy. Day & Son, Lithrs to the Queen.

Whenever a building site, or a new infrastructural project starts it is of high importance that documentation of the area is carefully done, especially by non-governmental institutes and local indigenous people. The HUL approach and the fieldwork assignment gave me several ideas on how to integrate design into the existing infrastructure of the site where once a cemetery was. One of those ideas focuses on the engagement of indigenous people in research, design, and planning which is of high importance. As discussed during the Heriland course, we should not take decisions without involving them, especially when it comes to heritage sites.

Figure 4. Infrastructure to bury the graves-taken with my Phone on 11 Dec 2017 behind the grave we can see parts of the Museum of Tolerance.

In 2017, during a seminar on social design at Bezalel, we focused on a building near the cemetery. A fellow student from the ceramic and glass department, Yusuf Rajabi, researched a small sculptural object placed in Muslim cemeteries named the “Shahed” which translates to “the witness”. He developed a unique standing sculpture that carries the site’s narrative. It was later adopted into an indoor workshop. Rajabi’s concept of the Shahed could be adopted into the open public spaces surrounding the cemetery and its former boundaries, to serve as an Obelisk, to remind everyone of the existence of the cemetery.

The opportunity during the Heriland course to meet many people from different backgrounds also gave me new ideas which I did not have before. It enabled me to exchange knowledge, strategies, tactics, and resources. Notably, my classmate Irene Fogarty pointed out that the 13th Session of the UN Human Rights Council passed a resolution denouncing Israel’s desecration of Mamilla cemetery.

Bibliography

Fatih Yavuz, M. (2018). Palestine’s Mamilla Cemetery and Israel’s Colonial Project. [Online]. Memo: Middle East Monitor: Creating New Perspectives. Published on January 25. Acess: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20180125-palestines-mamilla-cemetery-and-israels-colonial-project/

Mansour, R. (2010). Desecration and Destruction of Mulsim Cemetery in Jerusalem- Letter from Palestine. [Online]. United Nations published on 23/04/2010. Access: https://www.un.org/unispal/document/auto-insert-180001/

Center for Constitutional Rights. (2011). Jerusalem Municipality Destroys Cemetery Headstones, Approves “Museum of Tolerance” Construction. [Online]. Published on June 29. Access: https://ccrjustice.org/home/press-center/press-releases/jerusalem-municipality-destroys-cemetery-headstones-approves-museum

Harhash, N. (2019). Mamilla’s Face of Intolerance: A Park on a Graveyard. [Online]. Personal blog of Nadia Harhash. Published on September 22. Access: https://nadiaharhash.com/en/2019/09/22/mamillas-face-of-intolerance-a-park-on-a-graveyard/

Campaign to Preserve Mammilla Jerusalem Cemetery. (2010). Petition for Urgent Action on Human Rights Violation By Israel: Desecration of the Ma’man Allah (Mamilla) Muslim Cemetery in the Holy City of Jerusalem. [Online]. Access: https://www.badil.org/cached_uploads/view/2021/04/25/mamilla-addendum-1619361745.pdf

Unknown. (2010). A4. Campaign to Preserve Mamilla Jerusalem Cemetery, Petition for Urgent Action on the Desecration of Mamilla Cemetery, Jerusalem, 10 February 2010. [Online]. Journal of Palestine Studies. Vol. 39. No 3. Spring 2010. Access: https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/42317

Pierotti, E. (2013). Jerusalem Explored Being A Description of the Ancient and Modern City, with numerous illustrations consisting of views, ground plans and sections. Vol II- Plates. [Online]. Translated by Bonney, T, G. Cambridge University, printed by C. J. Clay, M. Access: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/44241/44241-h/44241-h.htm

Rajbi, Y. (2017-2018). Action Seminar: Radius 100- Social Design for Social Entrepreneurship (1. Shahed: Witness). [Online]. Pilot Projects, Research + Innovation. Pages 96-97. Access: https://online.fliphtml5.com/txvqn/wujq/#p=96

About the author

Ismael is a Graduate Student in Urban Design at Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design, Jerusalem. This Blog post was inspired by his research in Jerusalem and based on his participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2022.

Contact Ismael Pharoun: ismael.pharoun@gmail.com

About the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”?

Contact Niels van Manen: n.van.manen@vu.nl.