By Grace Emely

The topic of post-colonial heritage can be a challenging one. The dark history that it holds might bring unpleasant memories to some people. At the same time, others will be mesmerised by its beauty. It often provokes opposite feelings (Lee & Shu-Mei, 2022).

Figure 1. View of Sawahlunto (Author, 2019)

In July 2019, just before the Covid-19 pandemic broke out, I had the opportunity to visit a small town in West Sumatra, Indonesia. It required a long journey from The Netherlands, where I currently live. The journey’s first stop is Jakarta, the capital city of Indonesia. From there, I had to take a two-hour flight to Padang, in West Sumatra and continue the journey by car, for around 3 hours, driving through the green and hilly roads to a little town, Sawahlunto, at the foot of several hills.

Figure 2. Map of Indonesia, showing the province of West Sumatra (Rizky Fardhyan, 2019)

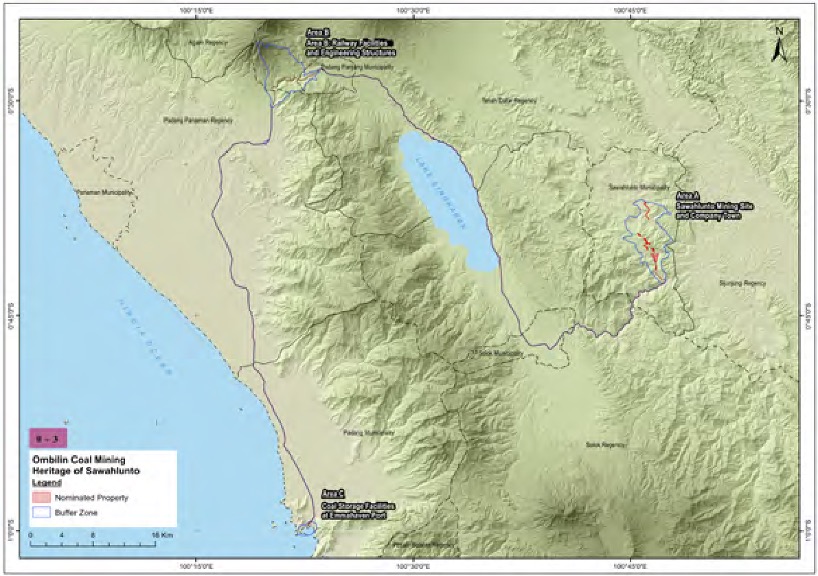

Figure 3. Map of West Sumatra, showing the listed World Heritage Property (Office of Cultural Affairs, Historical Remains and Museum, 2017)

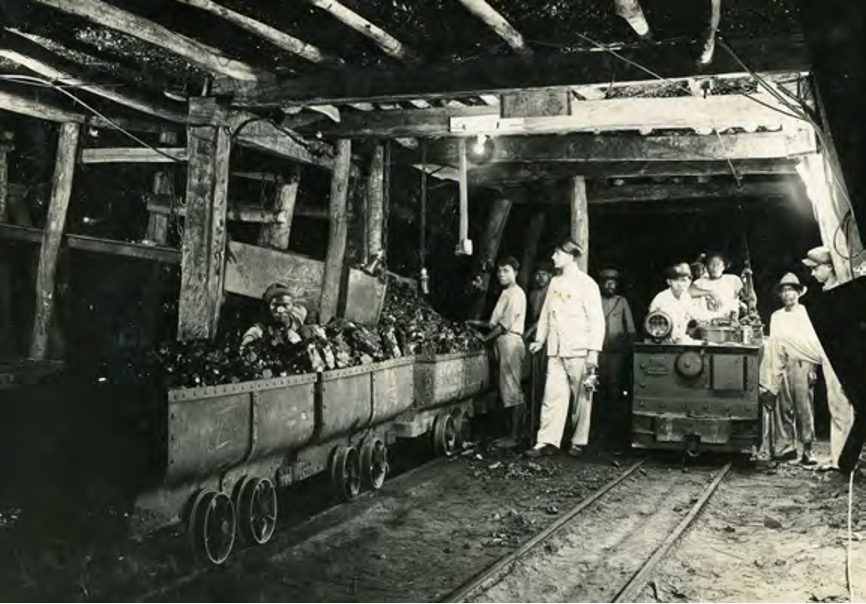

The town of Sawahlunto was established under Dutch colonial rule following the discovery of an abundance of mineable coal in the Sumatran highlands above Padang in the late 19th century. Once the first buildings and essential facilities had been built in 1887, developments over the following decades led the mining town to flourish.

Figure 4. Transport of coal using the Loento II Mining Pit (KITLV Collections).

The coal mining industry in Sawahlunto lasted for more than a century. The decrease in revenue made it impossible to sustain the operational costs, which forced the closure of the mine in 2002 (Martokusumo, 2016). Since then, Sawahlunto’s subsistence base has gradually melted away. The physical remains of the mining activities, however, have remained largely intact. The former mining complex encompasses not only the young town itself but also extraction sites, coal storage facilities, export facilities at the port of Emmahaven, and the railway network linking the mines to coastal facilities. The municipality of Sawahlunto felt the need to find an alternative solution to sustain the city for the future. Starting in 2015, the state of Indonesia adopted the “Sawahlunto Initiative” and nominated the historic mining town for UNESCO listing (Ministry of Education and Culture, 2017).

On 7 July 2019, right after my visit, the site was indeed enlisted as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, acknowledging Sawahlunto as one of the oldest mining towns in Indonesia, in a scenic natural setting and encompassing many historically valuable structures and practices (UNESCO, 2019). Since then, the municipality has been working hard to build a development plan. What development can feasibly be brought to the town taking into consideration and not harming the site’s heritage status?

Research has shown that the town has 3 major potential building blocks for development. The first two are the town’s well-established hospital or mining school. The third, tourism, is something that the municipality wishes to develop by propagating its heritage (Emely & Gebert, 2020).

Figure 5. Coal Processing Plant Compound, Area Saringan (Author, 2019).

Since Tourism is the main target of the municipal authorities, I will focus the remainder of the Blogpost on this strategy. When we talk about cultural heritage-related tourism, especially in the Global North, some people might have a strong opinion on how unsustainable it often is – both for the environment and the heritage itself – and how we therefore need to avoid mass tourism as a strategy in heritage planning. However, how realistic is that argument in the Global South, where the economy might be the main reason to drive heritage preservation and development? Only when an economical source is secure can one look into another alternative. If heritage-based tourism is potentially the most viable economic option, why not consider it seriously?

An example from the Global North that we can consider in comparison to Sawahlunto is the Zollverein Coal Mine Industrial Complex in Essen, Germany. In 2001, Zollverein was listed as a UNESCO world heritage for its important example of a European primary industry since the 19th and 20th centuries and the outstanding application of modern movement architecture (Zwergers, 2022). Right after the declaration, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA), a renowned Dutch architecture firm was commissioned by the Ministry of Culture, Sport and Housing of Nordrhein-Westfalen and the Development Company Zeche Zollverein, to create a masterplan for a contemporary use for the site. OMA proposed a new programme to be added to the site, without removing the existing machines that dominate the building. The result was an industrial monument that combines modern use within a historical context. Currently, the site attracts about 1.5 million visitors from across the globe each year to experience the exceptional industrial architecture, go on guided tours, visit exhibitions, celebrate festivals, and relax in Zollverein Park (Oevermann & Mieg, 2015).

Figure 6. The Zollverein Ice Rink (Jochen Tack / Zollverein Foundation).

Having the chance to visit the place myself in February 2019, I witnessed that the transformation has successfully maintained the site’s historical content while at the same time being the setting for cultural activities. Despite its lively activities around the museum, there was still some unoccupied area designated for artists or students to either sell their art or use the space for a practice centre.

The above example shows that even some places in the Global North still hold tight to tourism to boost their heritage while also developing its other more sustainable potential. However, indeed in the most extreme cases, several significant cities suffer from massive tourism, like Amsterdam and Venice, which are now trying to find a way to reduce tourism.

So now, the more appropriate question is, to what extent can we let tourism be a priority in developing the heritage? Moreover, when can we press the ‘slow down’ button when it happens? Being a World Heritage Site will make the city, town, or site more well-known, attracting many visitors. However, a question that is still to be further researched is, will tourism become the only way to boost the economy in the city? Or will there be another way to promote a historic city other than through tourism? It brings us back to the early statement that there is always a thin line between an acceptable and non-acceptable level of tourism. Where and how do we draw the line?

Bibliography

Emely, G & Gebert, V., (2020). ‘Sawahlunto: Towards a Sustainable and Attractive Place to Live, Work and Recreate’. Cultural Heritage Agency of The Netherlands, Amersfoort.

Ministry of Education and Culture of The Republic of Indonesia Government of West Sumatra . (2017). Nomination Dossier: Nomination for Inscription on the World Heritage List: Ombilin of Sawahlunto.

Lee, H., & Shu-Mei H. (2022). ‘”The ‘commodified’ colonial past in small cities: Shifting heritage-making from nation-building to city branding in South Korea and Taiwan.” International Journal of Cultural Policy 28, no. 5 (2022): 546-565.

Oevermann, H., & Mieg, H. (2015). Exploring urban transformations: Synchronic discourse analysis in the field of heritage conservation and urban development. Journal of Urban Regeneration & Renewal, 9(1), 54-64.

UNESCO. (2019). Ombilin has been included on the world heritage list of UNESCO. [Online]. Available at: http://traveltext.id/2019/07/09/ombilin-has-been-includedon-the-world-heritage-list-of-unesco/.

Martokusumo, W. (2016). ‘The Rise and Fall of a Former Mining Town Sawahlunto: Reflections on Authenticity and Architectural Conservation.’ In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians, Australia and New Zealand: 33, Gold, edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad, 418-428. Melbourne: SAHANZ, 2016.

Zwegers, B. (2022). “Zeche zollverein from eyesore to eyecatcher?” In Cultural Heritage in Transition: A Multi-Level Perspective on World Heritage in Germany and the United Kingdom, 1970-2020, pp. 131-156. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

About the author

Grace Emely is a graduate student from the Institute for Housing and Urban Development Studies. This Blog post is inspired by her findings on collaboration research with the Cultural Heritage Agency of The Netherlands, her travels and based on her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2022.

Contact Grace Emely: grace.emely@gmail.com

About the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”?

Contact Niels van Manen: n.van.manen@vu.nl