By Fleur Liedmeier

The Marineterrein is an area in Amsterdam that has evolved from 17th-century navy shipyards. After 350 years of ownership by the Dutch Royal Navy (a period during which various changes were made to the structure and use of the area), the biggest part of it is about to be sold to the municipality of Amsterdam. In its plans for the Marineterrein, the municipality tells a story of innovation. Honouring the site’s past, it highlights a history of innovation in shipbuilding. Confronted with today’s multiple crises, the municipality wants to expand on this and already describes the area as an ‘innovation district’ that addresses societal and environmental challenges. However, the municipality pushes innovation in a narrow sense only: technological fixes that relieve the symptoms of these crises, but obscure the real problems.

Meanwhile, the humanities and social sciences have been delving into the cultural roots of our socio-environmental problems and theorising ways to move forward as societies, addressing fundamental issues such as nature-culture dualism and alienation.[1] However, these theories have largely remained within the academic circles in which they evolved. We, as earth dwellers who depend on the livability of this planet, cannot afford this any longer. Therefore, I propose an alternative vision for the Marineterrein, as a multispecies, cultural and sociopolitical living lab for innovation in the broadest and deepest sense.

To walk you through this idea, I borrow the four tool sets of UNESCO’s Recommendation on the Historic Urban Landscape approach (2009): knowledge and planning; civic engagement; regulatory mechanisms; financial mechanisms.

Knowledge and Planning

Amsterdam has a long colonial history, to which it owes much of its current wealth. It also boasts a remarkable inclusivity, largely inherited from the strategic pacifism of, for example, Johan van Oldenbarnevelt. These histories might just converge in the Marineterrein, which was created for the construction of navy ships to defend the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC – East India Company) fleet.[2] Today’s reduction of the military opens up a large part of the Marineterrein for new uses. I propose that we use this space to transform our traditionally colonial relationships with the other-than-human, expanding our understanding of inclusivity.

Maps on maps.amsterdam.nl illustrate how Amsterdam is already a multispecies city, by showing, for example, the locations of bats in the city.[3] Yet, thinking from a multispecies perspective involves not just including other nonhuman animals, but whole ecologies too. The Marineterrein specifically has hosted long and rich collaborations between humans and water: shipbuilding, land reclamation, swimming and seeing, as well as current experiments, to name a few. This (largely intangible) heritage provides a starting point for thinking about future human-nonhuman collaborations.

Including nonhuman entities in our thinking is not an act of altruism: the ecosystem services they provide are fundamental to climate resilience, as well as to preventing or relieving other socio-environmental issues. Yet to really provide for their needs, we have to start seeing them as co-citizens.

About this Blog series & the Heriland Blended Intenstive Programme

The Blogs in this series (March-July 2024) were written by graduate students and early career professionals who participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2023 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme, “Heritage and Landscape Futures”, in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024?

Civic Engagement

Taking other-than-humans seriously as co-citizens means including them in our civic engagement. Bruno Latour has provided a model called “The Parliament of Things” for this purpose, which has been adapted into the speculative research project “Embassy of the North Sea”. This ‘embassy’ aims “[t]o emancipate the North Sea in all its diversity as a fully-fledged political player, via collectives of humans and non-humans,” through the phases of listening, speaking and negotiating.[4] Such engagement among humans and other species paves the way for a greater awareness of our mutual entanglements and interdependencies. The living lab framework creates a space to experiment with such forms of civic engagement.

Despite my claim to innovation, awareness of multispecies entanglements is not really new: it can be seen in indigenous communities worldwide. Nevertheless, it brings a much-needed change to the status quo of modern Western societies.

Regulatory Mechanisms

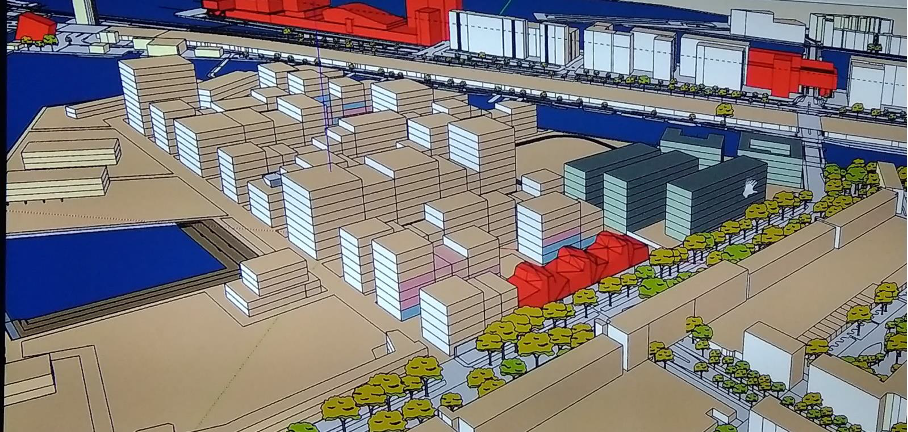

Without a doubt, the nonhuman stakeholders of the Marineterrein would have their own visions for the area. In this, they would add to concerns previously expressed by local human stakeholders about, among other things, the limited space for greenery and the plans for the housing blocks. According to the Werkgroep Ontwikkeling Marineterrein, these plans do not do justice to either the urban planning of Amsterdam or the historical significance of the area.[5]

In the current housing crisis, the topic of housing is bound to cause tensions. However, the framework of a living lab also creates space to experiment with alternative approaches to these problems, such as new regulations that promote shared housing instead of discouraging it. Through adaptive reuse, some of the current buildings would be suitable for this. In this way, we might start finding actual solutions to the housing crisis.

With some initial guidance, its residents could also experiment with forms of organisation such as sociocracy and collective caretaking of common areas, as well as the Parliament of Things mentioned earlier.

Financial Mechanisms

The multispecies living lab that I propose would not generate a lot of revenue. We can no longer afford to prioritise money anyway. The idea of infinite economic growth is a self-destructive delusion: we live on a planet with finite resources, close to tipping points with disastrous consequences. Especially the countries with a lot of wealth and large ecological footprints need to start working on degrowth. Reconnection with the more-than-human world plays a critical role in this: it increases our wellbeing and decreases our dependencies on, for example, our shopping addictions. Beside this, it also prevents future costs of mental and physical health.

Most of the Global North has resigned itself to a cultural and sociopolitical stagnation into business-as-usual, where economic models seem to replace natural laws, and critical theories exist only within the safety of their academic bubbles. We need imaginaries for the future that are bolder than that, starting from a recognition of our inherited multispecies interdependencies and extending into radical real-world practices. Capitalist business-as-usual is a choice that leads to environmental disaster. This process is already in action, as current climate refugees will confirm. But, such apocalyptic imagery does not need to send us into paralysis: by revealing the absurdity of business-as-usual, it also inspires what Bruno Latour calls ‘serious play.’[6] This proposal is an act of serious play. I hope you will join me.

Notes

[1] See the works of Donna Haraway, Val Plumwood, Bruno Latour, Eva Meijer and Jane Bennett, to name a few.

[2] “Marineterrein,” I Amsterdam, accessed October 25, 2023, https://www.iamsterdam.com/en/whats-on/calendar/attractions-and-sights/sights/marineterrein.

[3] Vleermuizen, interactive map, accessed October 25, 2023, https://maps.amsterdam.nl/vleermuizen.

[4] “About,” The Embassy of the North Sea, accessed October 25, 2023, https://www.embassyofthenorthsea.com/over.

[5] “Zienswijze van organisaties uit de omliggende buurten op de concept Nota van Uitgangspunten voor het Marineterrein,” Werkgroep Ontwikkeling Marineterrein, accessed October 25, 2023. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5427ba88e4b06b86fdab08dc/t/61efcec2ff91b0548192820c/1643105992241/Zienswijze+Omliggende+buurten+Concept+NvU+Marineterrein.pdf.

[6] Cited in Donna Haraway, Noboru Ishikawa, Scott F. Gilbert, Kenneth Olwig, Anna L. Tsing, and Nils Bubandt, “Anthropologists Are Talking – About the Anthropocene,” Ethnos 81, no. 3 (May 26, 2016): 535–64.

About the author

Fleur Liedmeier has studied Environmental Humanities at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, The Netherlands. This Blog post is inspired by her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2023, an experience which she has sought to bring into dialogue in this post with her expertise in Environmental Humanities.

Contact Fleur Liedmeier: blancefloer@hotmail.nl

About the Amsterdam Marineterrein MiniSeries

During the Heriland Blended program Multispaces Living Lab, students worked on the Amsterdam Marineterrein to prepare proposals. This is the Second of three posts presenting a heritage-informed perspective on the Marineterrein, part of the historic docks of Amsterdam.