Figure 1. Street in Wiesbaden, Germany. (Author, 2024).

by Jil Kremser

What is post-colonialism?

Relations between the Global North and the Global South are still fundamentally shaped by a shared past of colonisation. Postcolonialism addresses the persistence and after-effects of patterns of colonial rule. While walking around in my hometown, Wiesbaden, in Hessen, Germany, I got curious about colonial traces. In this Blog post I will share my findings.

The aim is to show examples of places whose significance or history are inextricably linked to German colonialism. This is a topical issue in Germany, which is often the subject of heated debate. One example is the Humboldt Forum where the display of looted colonial artefacts paired with the architectural characteristics of the building fuels ongoing debate.

About this Blog series & the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme

The Blogs in this series (March-July 2024) were written by graduate students and early career professionals who participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2023 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme, “Heritage and Landscape Futures”, in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024?

Colonialism

Colonialism is fundamentally understood as a mechanism of domination, involving the exertion of control by individuals or groups over the territory and behaviour of others (Horvath, 1972). Historically, it was the overseas policy of a state aiming at possession or the domination, expulsion, or murder of a people by a people from another culture, whereby the conquered territories were completely oriented to the interest of the colonial rulers and thereby deprived of their own historical development (Schubert & Klein, 2020).

Its traces can still be felt in European cities, as well as in the former occupied territories, both materially and immaterial. Colonial mentality is defined as the perception of ethnic and cultural inferiority and a form of internalised racial oppression.

As a resident of Wiesbaden, I’m deeply invested in the critical reassessment of colonial heritage. However, I find that Germany’s efforts in this regard are insufficient. There’s a glaring lack of discussion, receptiveness, and accountability. Despite numerous calls from advocacy groups and citizens’ initiatives, meaningful action often falls short. Here the difficulty of ambivalence exists. If we remove controversial monuments, we may also erase the memory of them. If we leave them standing, we do not question the past and offer perpetrators a stage in public space. There is an urgent need to find ways of dealing with these examples from a monument preservation point of view and, above all, to involve those in the discussion who are affected by the difficult legacy.

Example 1: Bismarck – Monument (see figure 3)

The Bismarck monument was created by Prof. Ernst Gustav Herter (1846-1917) and shows Bismarck as the “iron chancellor” with his imperial insignia: crown, sceptre, sword and protected under the eagle of Prussia. The monument was erected in Wiesbaden after his death and moved to the Nerotal park when the original site was abolished. On Bismarck’s classification:

“The ruthlessness towards African interests and African ruling contexts – the colonial borders cut through clan and social structures, separated what belonged together and crammed strangers and even enemies into common state structures – became a mortgage also for independent Africa and the cause of sometimes virulent minority conflicts. A global historical appreciation and remembrance of Bismarck must take into account the global effects of his actions.” (German Federal Agency for Civic Education)

So what does one do with such a monument? Can one simply exhibit this historical actor in one’s city and directly or indirectly represent colonial values? The ruthless imposition of colonial borders and disregard for African interests must be acknowledged in any assessment of Bismarck’s global impact. Therefore, a critical reevaluation of the monument’s place in the urban landscape is imperative to confront its historical significance and address potential implications regarding colonial values.

Example 2: Colonial street names (see figures 5 and 6)

Bernhard von Bülow (1849-1929), Secretary of State of the German Foreign Office, famously expressed the desire for Germany to claim its place in the world:

“The times when the German, left the earth to one of his neighbours, reserved the sea for the other and the sky for himself (…) these times are over” and further “We do not want to put anyone in the shade, but we also demand our place in the sun.”- Reichstag speech on December 6, 1897.

Gustav Nachtigall (1845-1885), African explorer and supporter of the establishment of the German colonial empire in Togo, Henry Morton Stanley (1841-1901) “Bula Matari” and Joachim Nettelbeck (1728-1824), a chief steersman on enslavement ships, colonial advocate, and revered figure in German nationalism. What do they have in common?

These figures from colonial history continue to linger in Wiesbaden’s streets, their names uncontextualized and seemingly unaffected by the weight of their actions. Yet, where is the reckoning with colonial history, with those who perpetuated it, and the enduring impact it has had? Shouldn’t our streets be named after individuals who made positive contributions to society, rather than those who upheld oppressive systems and ideologies?

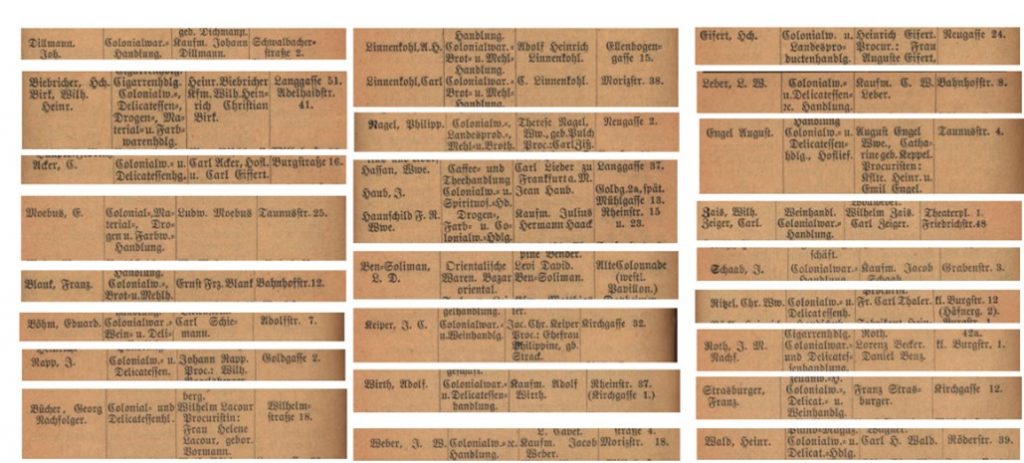

Example 3: Colonial goods store and colonial exhibition in Paulinenschlösschen (see figures 7 and 8)

The expansion into non-European territories led to the emergence of colonial goods stores, which became integral parts of daily life for many people, offering a variety of products like sugar, spices, coffee, and tobacco. However, the landscape of these stores shifted over time, with supermarkets and large department stores gradually replacing smaller local grocers.

In Wiesbaden, around 1893, the city boasted numerous grocery stores, most of which are no longer in existence today. Additionally, colonial exhibitions were held in Wiesbaden during various periods, including in 1899, 1935 at the Nassau Museum, and in 1941 at the Paulinenschlösschen.

During the Nazi era, the colonial period was exploited to justify their expansionist policies. Publications such as the Nassauisches Volksblatt in 1941 reflected this sentiment, with statements implying a desire to reclaim what was perceived as lost during the colonial era. The exhibitions were presented as demonstrations of Germany’s former colonial glory, further fueling nationalist sentiment. The question of whether buildings and sites from the colonial era should be marked is one of complex significance and evokes diverse opinions. Some argue that marking is necessary to acknowledge historical responsibility and educate the public about the past. By identifying such locations, individuals may be encouraged to engage with colonial history and recognise the continuity of colonial patterns in the present.

Some may argue that marking such places could shift focus to past injustices rather than concentrating on the present and future. A compromise might involve implementing appropriate and informative marking that considers historical contexts and diverse perspectives.

What to do with the colonial “heritage”?

How is Wiesbaden addressing its colonial heritage today? The city’s museum is taking steps to revamp its collection, with a commitment to indicating the origins of looted artefacts in the future. Additionally, they are offering “Postcolonial Walks”, providing a critical review of Wiesbaden’s colonial history.

However, in my view, these measures may fall short. Beyond these initiatives, there’s a need to consider urban planning strategies, especially in dealing with streets bearing colonial names. A limited tour won’t suffice; on-site actions involving classification and education are crucial. Germany’s monument preservation faces a challenge: balancing the loss of monuments that facilitate discussion with the demands of postcolonial associations.

Tahir Della’s insight, “The former colonizers, the Global North still determines the framework, the negotiations of how colonial history is reappraised & made visible,” highlights a significant aspect. To me, the key to this reappraisal lies in education and contextualization. The specific approach, whether through renaming, additional signage, artistic reinterpretation, or even demolition, should be subject to public discussion. Engaging all stakeholders in a public discourse is essential for societal development concerning our shared past.

Bibliography

Adressbücher / Adressbuch der Stadt Wiesbaden: (1892-1893). Wiesbaden. (2023). [English translation: Address books / Address book of the city of Wiesbaden: (1892-1893). Wiesbaden. (2023).https://hlbrm.digitale sammlungen.hebis.de/adressbuecherhlbrm/periodical/structure/3062778, last accessed on 22.01.2023.

Bismarck-Denkmal Landeshauptstadt Wiesbaden (2023). [English translation: Bismarck Monument. State capital Wiesbaden (2023).] https://www.wiesbaden.de/microsite/stadtlexikon/a-z/bismarck-denkmal.php, last accessed on 21.01.2023

Bpb. (2012).Kolonialismus. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. [English translation: Bpb. (2012). Colonialism. Federal Agency for Civic Education.https://www.bpb.de/shop/zeitschriften/apuz/146987/kolonialismus/, last accessed on 21.01.2023.

Horvath, R. J. (1972). A Definition of Colonialism. Current Anthropology, 13(1), 45–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2741072

Kolonialausstellungen [Hessen (post)kolonial]. (2023). [English translation: Colonial exhibitions [Hesse (post)colonial] (2023).https://www.online.uni-marburg.de/hessen-postkolonial/doku.php?id=de:koloniale_repraesentationen:kolonialausstellungen, las accessed on 22.01.2023.

Russ, S. (2005). Historisches Fünfeck. [Stuttgart]

Schubert, K. and M. Klein, Das Politiklexikon. Begriffe. Fakten. Zusammenhänge.(2021). [English translation: The Politics Lexicon. Concepts. Facts. Connections.]. Dietz.

About the author

Jil Kremser is a Master student at the University of Applied Sciences in Wiesbaden, Germany, where she studies architectural heritage conservation. During semester breaks she has participated in archeological excavations in Turkey and has dealt with site management and historic building research. This Blog Post was inspired by research in her master’s programme and the insights gained during the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2023.

To contact her use this email address: Jilkremser.info@gmail.com

About the Controversial Monuments Series

During the Heriland Blended program Multispaces Living Lab, students worked on many themes, including National Parks and Controversial Monuments. This post is the first of two proposal blog posts prepared by two different participants on the latter subject. Next week, another proposal from the Controversial Monuments series will be published.