Figure 1. Reforma Avenue from the air (2018), Source: Wikimedia Commons.

by Paulina Beltrán Alessio Robles

Originally built to connect the palace of an emperor and the center of the city, Paseo de la Reforma is arguably the most important avenue in Mexico City. It is advertised for tourists, closed for bicycling on Sundays, and where some of the most expensive hotels and businesses are located. Parades are normally held there and go to the Zócalo, the city’s main square, for occasions such as “Día de Muertos” and Independence Day. Reforma has big sidewalks, is flanked by museums, and modern skyscrapers, as well as many sculptures of the fighters of the War of Reform, and many others celebrating, for instance, Aztec heroes or the Mexican Independence. It has a huge number of public landmarks and monuments, both at its sides and in the centers of big roundabouts.

About this Blog series & the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme

The Blogs in this series (March-July 2024) were written by graduate students and early career professionals who participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2023 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Are you interested in participating in the next iteration of the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme, “Heritage and Landscape Futures”, in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024?

On the other hand, Paseo de la Reforma is also one of the most politicized streets of the capital and the country itself. Protests march through it, regularly from the Angel of Independence to the Zócalo. Be it feminist marches, commemorations of violent acts, union demonstrations, pro-politicians, or anti-politicians, it is one of the frequent places to mobilize. Occasionally, some of these protests resort to slogans painted with graffiti, breaking windows and damaging businesses. The demonstrations can also be semi-permanent like camp-outs in the street or in front of some institutions.

Both ways of appropriating the avenue are close to me: I enjoy strolling and cycling through Reforma, I have a deep appreciation for its history, and have guided tours in the area. I have also taken part in some marches that have taken place there, particularly feminist protests and those that claim justice for the disappearance of rural teacher-students of Ayotzinapa in 2014.

Since 2015, anti-monuments have also come to stand in the avenue, through the illegal installation of politically themed sculptures. They are put there as a way to remember injustices, ongoing violence, and oppression, perpetrated against a group of victims, as well as the failure of the State to solve these cases and to keep them from happening in the first place, they are an emblem of a struggle or a cause [1,2].

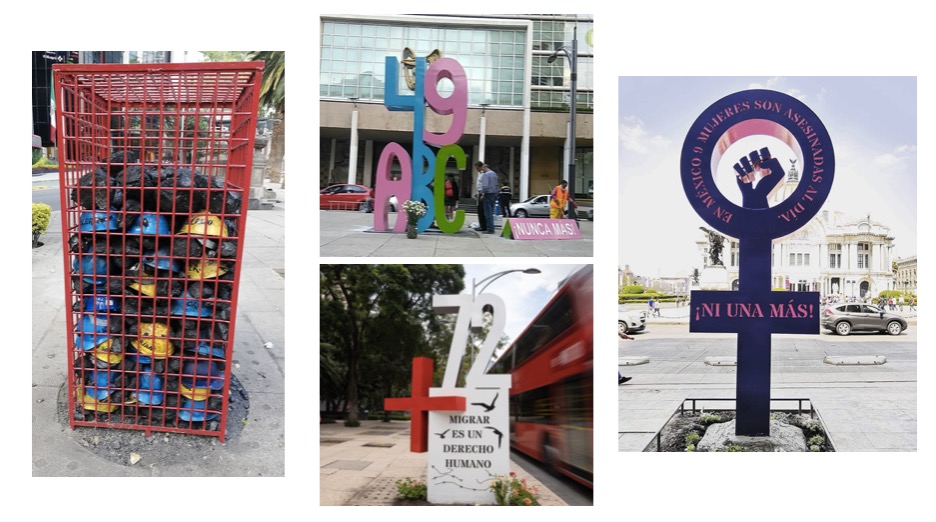

It all started with the installation of a big red sculpture that read “+43” remembering the 43 students from Ayotzinapa and all the others who have disappeared in Mexico. Since then, anti-monuments memorializing trapped miners, children who died in a daycare fire, migrants assassinated while crossing Mexico, and other movements from the past, like the student massacre of 1968, have been planted as a form of demonstration. As more of them appear, a Memory Route has formed [3,4].

Monuments tell one story or one version of history, as they are paid for and built by the State, while anti-monuments are more collective, ambiguous, and unfinished in their stories, as they symbolize pending issues [2,4]. They are supposed to be ephemeral, designed to be taken down once justice or accountability is served. Anti-monuments lack legal protections but are sustained through community participation.

This way, the anti-monuments reclaim public space, force the interlocution between the government and the citizens, and are a way to reshape the traditional narratives of history and heritage. With their size and preeminence, they modify the landscape and become landmarks, big objects that people associate with certain spaces of the avenue and the city.

One of the most paradigmatic examples is the roundabout that used to hold the monument to Christopher Columbus. As in many places throughout the world, from being seen as a hero and discoverer, the figure started being regarded as a symbol of colonization and genocide [5]. It had been a subject of protests before, but the government removed it a week before October 12th, 2020, as people were organizing online to take it down. The pedestal was still there, and while the government recognized Columbus would not be back, and planned for a sculpture of a nameless indigenous woman; one night, feminist protesters planted a new small purple anti-monument of a girl raising her fist, with the word justice supporting her back, and renamed it “The roundabout of women who fight”. Since then, multiple demonstrations and acts of activism have taken place there [3].

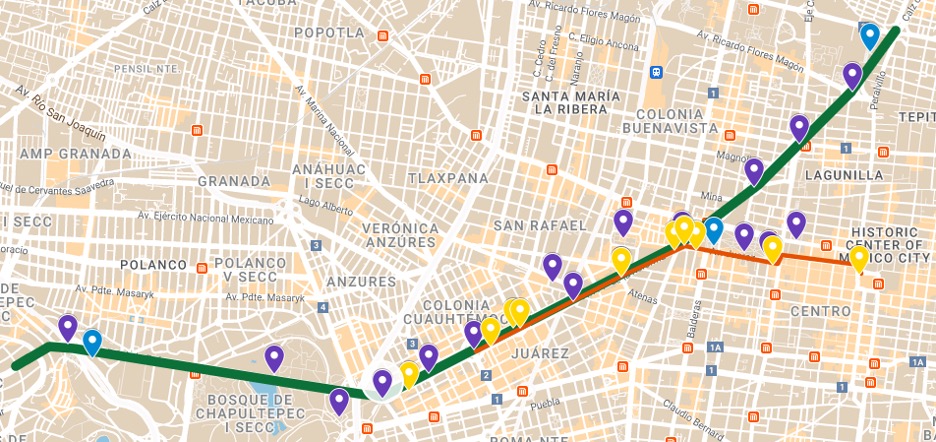

Like the monuments in the avenue, some anti-monuments are divisive, some are widely supported, and some have become part of the everyday landscape. But now, when we walk or drive through the avenue and then Juárez Street towards the Zócalo, we see the history of the Nation-State side by side with the challenges to that narrative, the memories of past and present grievances.

This brings the question: Can authorized Heritage Discourse [6] live alongside unauthorized discourses, particularly when they are in direct opposition? One trying to celebrate the State and the other openly criticizing and challenging it?

I argue that this is already happening. Most of the anti-monuments have not been removed, or are not being actively threatened, the +43 one, is now 8 years old. In fact, I believe the avenue already shows an intriguing visual polyphony of narratives.

Although the future of some other spaces like the roundabout of the Disappeared is less certain, the sheer popular support keeps the anti-monuments standing. They are not a good look on the government, but removing them might signal a complete disinterest in providing accountability to the different causes. Nevertheless, with changing governments, or if justice is ever served, the permanence of the anti-monuments is not imminent.

Therefore, mapping both monuments and anti-monuments in Reforma Avenue and Juárez Street is a good way of showcasing and knitting together multiple and changing versions of memory and history, and also delineating the material changes, like the installation of anti-monuments, removal of statues or re-naming of roundabouts.

This example shows that if the traditional ideas of heritage are usually linked to monumentality [7], the idea of heritage as a process, as something that is changing and holds significance for different groups, is not necessarily completely foreign to it either. Challenging the official, top-down narratives can be done with the same tools traditionally used and in the very same landscapes. If we observe the anti-monuments through the lenses of heritage we can see a great example of citizen participation from a clear bottom-up perspective.

Despite its possible characterizations as dark, sad, contested, or conflicted heritage, the anti-monuments are people-based, they are an example of taking back the right to the city [8] and might be more meaningful to many than some other monuments embellishing Reforma.

In the end, what is more interesting to me is that, when we walk along Reforma and Juárez the two opposing narratives stand together. Side by side, the glorious official history, and the painful memory discourse present us with a richer, more nuanced, and more complex history and heritage, even if it is only through sculpted objects on the street.

Bibliography

- Tello Arista, I. (2021). Arrebatar las narrativas. Revista de la Universidad Nacional. May. https://www.revistadelauniversidad.mx/articles/8fd237c9-66e0-467c-9d72-f9028779935a/arrebatar-las-%20narrativas

- Díaz Tovar A. & Ovalle, L. P. (2018). Antimonumentos. Espacio público, memoria y duelo social en México. Aletheia, 8 (16). http://www.memoria.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/art_revistas/pr.8710/pr.8710.pdf

- N. A. (2021). Antimonumentos, Memoria, Verdad y Justicia. Heinrich Böll Stiftung. Mexico City. https://mx.boell.org/sites/default/files/2022-08/antimonumentos.pdf

- Délano Alonso, A., & Nienass, B. (2023). Memory Protest and Contested Time: The Antimonumentos Route in Mexico City. Sociologica, 17(1), 9–23. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.1971-8853/16942

- Melgar, L. (2022). La glorieta de las mujeres que luchan: memorial y lugar de encuentro. Revista con la A. 84. November 25. https://conlaa.com/la-glorieta-de-las-mujeres-que-luchan-memorial-y-lugar-de-encuentro

- Smith, L. (2006). Uses of Heritage. New York. Routledge.

- Ashworth, G. (2011). Preservation, Conservation and Heritage: Approaches to the Past in the Present through the Built Environment. Asian Anthropology. 10 (1). DOI: 10.1080/1683478X.2011.10552601

- Harvey, D. (2008). The Right to the City. New Left Review. 53. September. https://davidharvey.org/media/righttothecity.pdf

- To see more: https://www.google.com/maps/d/u/0/viewer?mid=1O579cPJXJX31Ixhdtev-uhwyl0Va48U&ll=0%2C0&z=14

About the author

Paulina Beltrán Alessio Robles is a Master’s student in Conservation at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden. This Blog Post was inspired by her personal experiences and research in Mexico and the insights gained during the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Cultural Heritage and the Planning of European Landscapes”, October 2023.

Contact Paulina Beltrán Alessio Robles: gusbeltpa@student.gu.se

About the Controversial Monuments Series

During the Heriland Blended program Multispaces Living Lab, students worked on many themes, including National Parks and Controversial Monuments. This post is the flast of two proposal blog posts prepared by two different participants on the latter subject.