By Carrie Bobo

The tangible and intangible cultural heritage of medieval feminist cities suggests a way forward for urban environments, toward a more sustainable future.

Description

We live in cities shaped by men. What if the future of cities were shaped exclusively by women? Co-housing and intersectional feminism are seen as contemporary architectural responses to complex challenges; but consideration of the complexities of co-occurrent identities and architectures responding to them have existed for 1000s of years. The UNESCO heritage protected cloistered beguinages, built in the late 13th century, for, and occupied by, communities of only women, offer contemporarily relevant solutions to the construction of efficient, desirable, sustainable, climate responsive building forms. The invaluable tangible and intangible cultural heritage of the beguinage’s feminist landscape offer lessons that can and should be applied at the scale of the city, to shape better, more caring, future urban landscapes.

About This Blog Series

This is the first blog post of the series of 24 blogs prepared by graduate students and early career professionals who shared their views on the future of heritage and landscape planning.

The writers of these blogposts participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2024 in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Cities Shaped by Men

‘‘The streets of the new city have nothing in common with those appalling nightmares, the downtown streets of New York,’’

Le Corbusier 1929

While the world has, in some ways, moved on from the anti-urbanist, functional modernism of the Swiss-French architect, Le Corbusier, the specter of his obsolete ideas defines the shape of today’s cities. He assumed he knew better than what came before and proposed a radical break with the history of urban development including the demolition of vast swaths of cities. His 1920s-30s urban designs segregated use, a functionalist, hyper rationalism that underestimated the affordances of urban complexity. Yet, many were (and still are) misled by the allure of his drawings and writing, missing their negative impacts (for more on this, Dunnett, 2011). This type of thinking later influenced the doomed, albeit for more complex reasons, modernist housing projects of the 60s and 70s (Jacobs,1961, p. 23; Jacobs, Hirt, Zahm, 2012, p. 248), and presaged the elevated superhighway systems of America along with their environmentally unsustainable cause, automobile-dependent commuting.

In the United States, Le Corbusier’s compartmentalization enabled structural racism, urban/suburban segregation as a response to forced integration. Financial districts became places of work activated during daytime hours largely by white men and left desolate in the evening. Their surroundings became aggregators of poverty and otherness, while suburbs became an isolating domain for white women and children (Massey, Denton 1989; Rothstein, 2018). Racism, together with Le Corbusier’s functionalism, begat misogynist built-environments (Hayden, 1980; Saegert, 1980).

So, what if we imagine a different societal future? What is the counterpoint to the hubris of Le Corbusier’s urban designs, and how might we build on our urban cultural heritage rather than tear it apart? What if women, rather than men, had shaped the history of urban development? If we posit Corbusier’s work as masculine, what might a feminine, feminist, or even, ecofeminist, future city look like?

‘‘To see complex systems of functional order as order, and not as chaos, takes understanding.’’

Jane Jacobs 1961

City of Ladies

In 1405, Christine de Pizan wrote, City of Ladies, featuring a symbolic city, a city as metaphor, arguing against the disparagement of women (Christine, 1405; Haralambidou, 2020). At the same time, across Western and Southern Europe we see the construction of thousands of beguinages, female only communities; communities historians later called by the same name as de Pizan’s book, Cities of Ladies (Simons, 2020).

These ladies, the Beguines, groups of religious lay women, emerged during the early 13th century. Named for the derogatory slur often used against them (perhaps an early derivation of beggar), remarkably, built a sheltered independent, yet communal life. They supported themselves and others through the creation of works of renowned beauty – textiles, illuminated manuscripts, and literature while stabilizing society, providing a safety net – housing the poor, educating the uneducated, caring for the sick, and integrating the newly arrived (Swan, 2014).

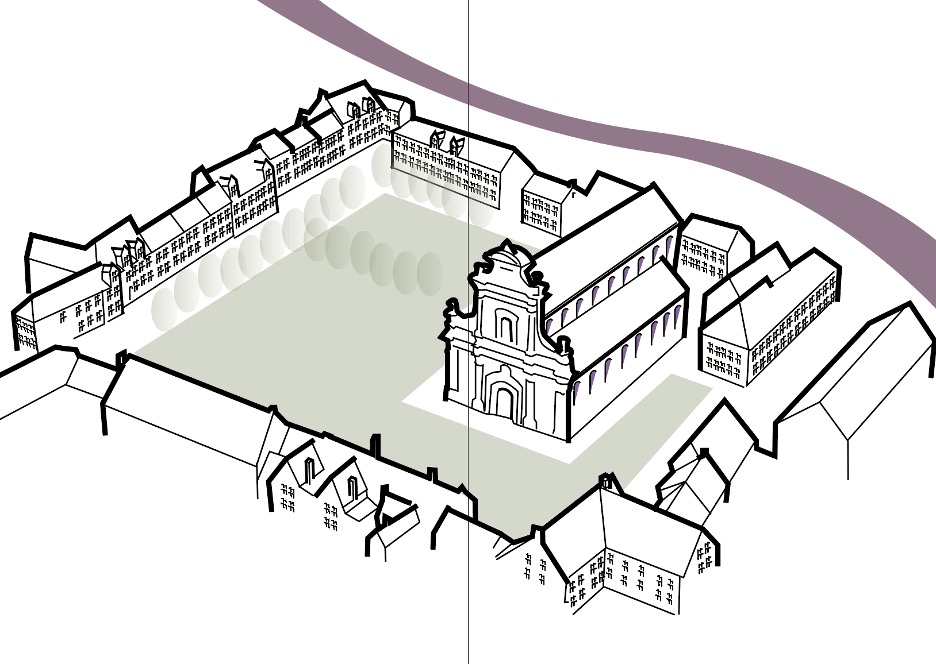

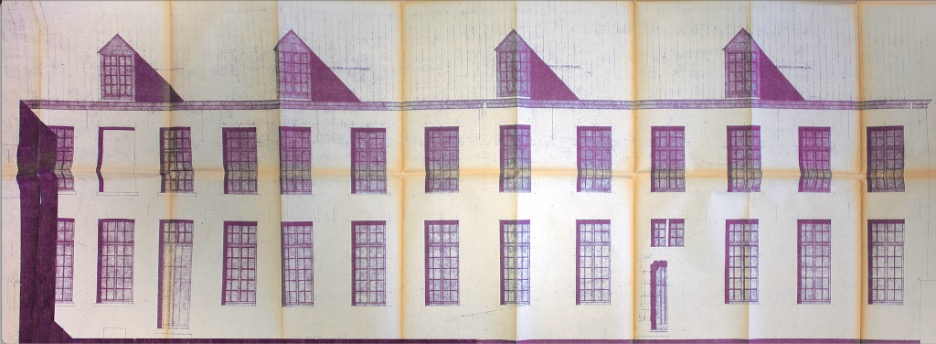

Among the works of beauty left behind, are the cloistered constructions they lived within. More than 800 years after their founding, these structures are highly sought after, oases of calm, that accommodate both individual privacy as well as meaningful connection to community life. Built before the modern conveniences of mechanized climate control and electric lighting, and for a community that embraced poverty, these buildings are models of efficiency, sustainability, and local response to climate. These courtyard forms mixed production, worship, play, rest, and home – all within one urban construction, with a density of roughly 5,500 inhabitants per square kilometer, well denser than the city as defined by the degree of urbanization (DEGURBA) by the European Commission (Dikjkstra, 2014) and just slightly denser than the socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable 15-minute city.

Intangible Heritage

These cities of ladies are inscribed in UNESCO’s heritage list with criteria that refer to both their physical structure and their cultural tradition. Cultural traditions are the intangible heritage of the beguines, and the beguines were remarkable. Despite living in a patriarchal society, which viewed women as inferior and corrupting, the Beguines shaped a feminist world before the term existed (Salembier, 2023). They built cities of care.

Zooming out to feminist theory, Carol Gilligan’s ethics of care posits women as emphasizing compassion and empathy over abstract duties, rationalism, and morality (Gilligan, 1982). Gender Feminism asks, have compassion and empathy been historically undervalued because a misogynist society devalues the priorities of women (Tong, 2009)? This devaluing of care allowed for the rise of functionalism and its negative impacts on cities. The beguinages offer an alternative.

Conclusions

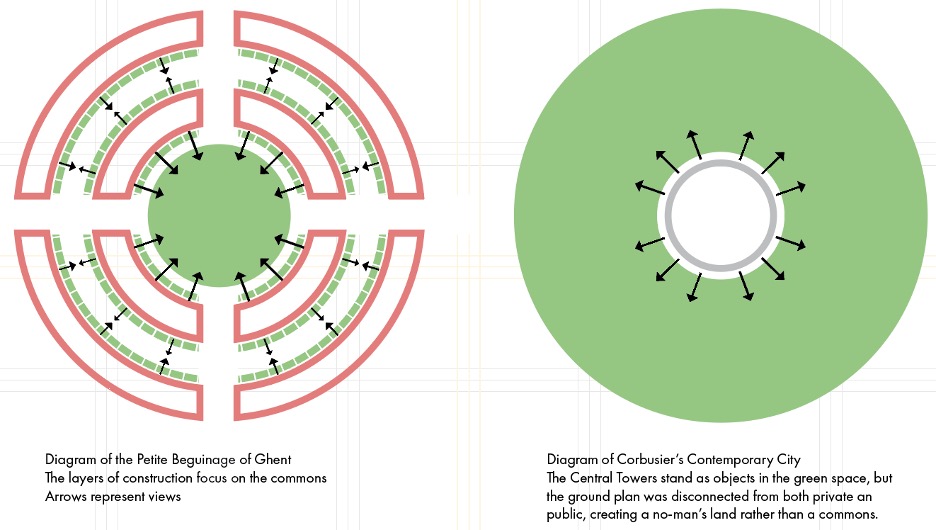

I would argue that in many ways the Beguinages represent an inversion of Corbusier’s Contemporary City, the feminist city versus the masculine one. In the Beguinages, living and working spaces were one and the same. Rather than buildings isolated as phalluses within fields of green, the warm, earth-based materials of the buildings framed green, working courtyards, the field becoming the center, the commons, both literally and figuratively, as the focus. Today, the commons conceptually represents a call to “rethink how public and private assets can be delivered for the common good”, emphasizing decolonization, de-carbonization, co-production, and equity, (Kolioulis, 2022, page 3). In this, we can see the commons, both intellectually and in built-form, as a prioritization of care.

If we build on the model of the Beguinage and collectively prioritize care, how could the shape of our society change? When women alone determine the physical form of the places we live, new opportunities appear. The UNESCO heritage protected cloistered beguinages, built in the late 13th century, for, and occupied by, communities of only women, offer contemporarily relevant solutions to the construction of efficient, desirable, sustainable, building forms that focus on caring for society. These (intangible) cultural traditions created a unique (tangible) built form that offers lessons that can and should be applied at the scale of the city, to shape better, more caring, future urban landscapes.

Bibliography

Christine, D. P. (1405) The Book of the City of Ladies. [Paris: Publisher Not Identified] [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2021667679/.

Dijkstra, L., & Poelman, H. (2014). A harmonised definition of cities and rural areas. Regional Working Paper 2014. https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/sources/work/2014_01_new_urban.pdf

Dunnett, J. (2000). Le Corbusier and the city without streets. Modern City Revisited, 68–91. 10.4324/9780203992036-9

Gilligan, Carol (1982). In a different voice: psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 10.1111/j.1471-6402.1985.tb00902.x

Haralambidou, P; (2020) The Female Body Politic: Enacting the Architecture of The Book of the City of Ladies. Architecture and Culture, 8 (3-4) pp. 385-406. 10.1080/20507828.2020.1794146

Hayden, D. (1980). What Would a Non-Sexist City Be Like? Speculations on Housing, Urban Design, and Human Work. Signs, 5(3), S170–S187. 10.1086/495718

Hayden, D. (1984). Redesigning the American dream: the future of housing, work, and family life. New York, W.W. Norton.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Random House.

Jacobs, J., Hirt, S., & Zahm, D. L. (2012). The urban wisdom of Jane Jacobs. Routledge. 10.4324/9780203095171

Kolioulis, Alessio. (2022). Defining and Discussing the Notion of Commoning. Gold VI Working Paper Series #14. Aprill 2022. Barcelona: United Cities and Local Governments.

Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1988). Suburbanization and segregation in US metropolitan areas. American Journal of Sociology, 94(3), 592-626. 10.1086/229031

Rothstein, R. (2017). The Color of Law: a Forgotten History of How our Government Segregated America (First edition). Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of W.W. Norton & Co.

Simons, Walter (2002) Cities of Ladies: Beguine Communities in the Medieval Low Countries, 1200-1565. University of Pennsylvania Press. 10.9783/9780812200126

Saegert, Susan. (1980). Masculine Cities and Feminine Suburbs: Polarized Ideas, Contradictory Realities. Signs. 5. 10.1086/495713.

Salembier, Chloé. (2023). Towards a Feminist Definition of Housing. Tijdschrift voor Genderstudies, Volume 26, Issue 1, Apr 2023, p. 98 – 104. 10.5117/TVGN2023.1.006.SALE

Swan, L. (2014). The wisdom of the Beguines: the forgotten story of a medieval women’s movement. Katonah, New York, BlueBridge, an imprint of United Tribes Media Inc.

Tong, Rosemarie (2009). Feminist Thought: A More Comprehensive Introduction (3rd ed.). Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press. pp. 162–65. 10.4324/9780429493836

About the Author

Carrie Bobo Gibbs grew up in Oklahoma where her family now raises bison on the open plains. She is currently studying cultural heritage preservation in Gothenburg, Sweden. This Blog post is inspired by her professional career in architecture and urban design, her graduate research on feminism’s impact on the structure of cities, and her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme, “Heritage and Landscape Futures”, in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024. Contact the author: www.officeforartandarchitecture.com