By Lakmali Kariyawasam Katukoliha Gamage

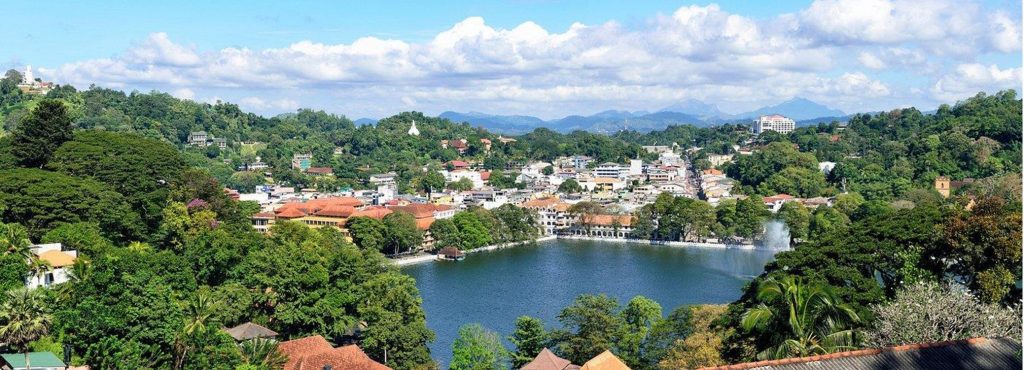

Kandy, the last capital of Sri Lanka before British colonization in 1815, is located in the Central Highlands at 1,640 feet above sea level. Surrounded on three sides by the River Mahaweli and the Hantane mountain range to the south (Fig.04), Kandy features an artificial lake at its heart. It was recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1988 under Criteria IV (typology) and VI (association), including landmarks such as the Tooth Relic Temple, the Royal Palace Complex, four shrines, Buddhist monasteries, and the Udawatta Forest Reserve. (ICOMOS, 1988)

The city embodies Buddhist world sovereignty and holds profound architectural, religious, and historical significance, with its urban layout reflecting a cosmic order and medieval grid planning, the royal palace and Sacred Tooth Relic Shrine showcasing meticulous craftsmanship, proportion, and scale, and its architectural value further enhanced by over 488 historic buildings.

About this blog post

This is the 9th blog post of the series of 24 blogs prepared by graduate students and early career professionals who shared their views on the future of heritage and landscape planning.

The writers of these blogposts participated in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme “Heritage and the Planning of Landscapes” in October 2024 in Gothenburg, Sweden.

Kandy also holds ecological importance through protected sites: the Victoria Randenigala Rantembe Sanctuary, the Udawatta Forest Sanctuary, and the Hanthana Mountain Range, which are home to diverse ecosystems and sustain local tea plantations integral to the city’s landscape.

Smith and Akagawa (2009: 6) state, “Heritage only becomes ‘heritage’ when it is recognisable within a particular set of cultural or social values, which are themselves ‘intangible.'” The culture, beliefs, customs, and traditions connected with the Temple of the Sacred Tooth Relic exemplify this concept.

The Annual Tooth Relic Procession (Dalada Perahera), one of the world’s most famous cultural celebrations to worship the sacred tooth relic, features over 100 elephants, 5,000 drummers, and vibrant dancers, symbolising faith, power, and traditions. It embodies the intangible values that connect the community across generations.

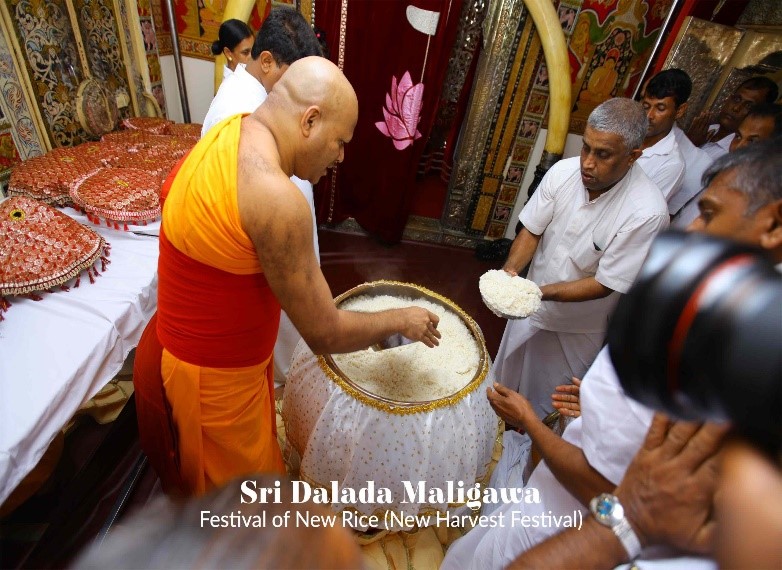

Beyond the procession, the temple hosts various rituals, including daily Hewisi Nada Pooja, weekly ceremonies like Nanumura Mangallaya, and seasonal festivals such as the New Harvest Festival, New Year Festival, and Kathrika Festival. These rituals highlight the continuity of tradition, cultural practices, and active community participation. More detailed information can be found by visiting the official websites: https://kandyesalaperahera.com/ and https://sridaladamaligawa.lk/.

Handicrafts and craft villages dedicated to Dalada Traditions contribute to the city’s intangible cultural landscape, specialising in drums, wooden carvings, textiles, Batik art, silver work, brass work, clay, and lacquer work, deeply interwoven with Kandy’s religious and social customs, strengthening its status as a “sacred living heritage” where tangible and intangible heritage are harmoniously combined.

Figure 8. Traditional hemp work and lacquer work – further reading https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kandyan_Art_Association/ & https://www.flickr.com/photos/kandyan_art_association

This tradition has survived throughout history despite facing numerous upheavals and political invasions, but currently, the city’s socio-cultural landscape is confronting several pressing challenges.

The Kandy city development proposal (UDA, 2019) identifies urban sprawl, illegal demolitions, overcrowding, strained infrastructure, and pollution as significant issues. During the Esala Perahera festival, the city’s limited infrastructure is overwhelmed, intensifying traffic congestion and environmental degradation.

Traditional craftsmanship is also in alarming decline, as modernisation draws younger generations to different career paths, leaving fewer artisans to preserve essential skills. (Wijesuriya, G. 2000 & 2005, Cindrebay, 2024) Deforestation and urbanisation further compound this issue by limiting access to raw materials needed for traditional crafts. The 1998 bombing at the Temple of the Tooth exposed this gap. A shortage of trained artisans in traditional skills hindered restoration efforts (stone carving), and sourcing materials (for woodworking) similar to the originals proved challenging. (Wijesuriya 2000; 2005) This growing disconnect between heritage practices and community livelihoods underscores the need for a comprehensive management system supporting tangible and intangible heritage preservation.

The Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach (UNESCO, 2011) emphasises integrating heritage into urban life rather than isolating it. It extends beyond preserving physical environments, focusing on tangible and intangible aspects. It advocates a holistic management system combining regulatory, financial, and civic engagement frameworks, integrating both top-down and bottom-up methodologies. It promotes multidisciplinary collaboration among experts and communities to develop an integrated management model considering the historic environment as an urban landscape shaped by the layering of cultural and natural values over time. It extends beyond traditional concepts of historical centres to the broader urban context, including topography, natural features, the built environment (historical and contemporary), open spaces, land use, spatial organisation, visual relationships, social and cultural practices, economic activities, and intangible heritage. These elements form the foundation for a comprehensive and sustainable framework for identifying, assessing, conserving, and managing historic urban landscapes.

This perspective inspires a holistic, sustainable management approach for Kandy, tackling its unique challenges through strategies beyond conventional top-down methods.

According to the Rahula 1956, Mahavamsa and Chulavamsa chronicles, and Epigraphia zeylanica in Sri Lanka (as cited in Wijesuriya G. 2020, Ratnayake & Mathota 2020), Kandy’s heritage was managed through the “Temple Custodianship System” under the “Rajakariya system“. (Britannica, n.d.) a community-based approach where local communities, under royal guidance, and religious custodians maintained religious sites. This system persisted until British colonization, which replaced it with an expert-driven, monument-focused approach. Some aspects of this traditional system still exist in Buddhist cultural society.

To address Kandy’s heritage challenges, an integrated management system is proposed that blends traditional knowledge systems (Wijesuriya and Court, 2020) with modern frameworks.

This approach would prioritise educational initiatives to revitalise traditional crafts, incorporating them into school curriculums, apprenticeships, and vocational programs. Recognising artisans as skilled professionals with financial incentives and conservation roles would ensure the future of traditional crafts. Formalising volunteer roles in cultural events like the Dalada Perahera would strengthen community bonds and help preserve vital cultural rituals. Sustainable tourism and improved infrastructure planning would alleviate pressure on Kandy’s heritage during peak periods. while collaborative governance among cultural, religious, and administrative stakeholders would encourage long-term commitment.

To address the challenges and protect its heritage, a sustainable framework must encourage collaboration across cultural, social, religious, political, and administrative sectors, involving local and international partners. The Enhancing Our Heritage Toolkit 2.0 (UNESCO, 2023) can be used to develop a management system based on the Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach. Governance arrangements, management planning, civic engagement, and regulatory tools will be key to solving major issues. A comprehensive management plan should integrate these elements, ensuring a long-term commitment to preserving traditional practices and cultural values. Heritage must not simply be part of the community and culture; it must embody them. Heritage management should not be an addition to existing systems but the system itself, intrinsically woven into every aspect of community life and governance. Revitalising traditional management through a mix of expert-led and community-based approaches will create a holistic, integrated model. This framework can serve as an inspiring global example of the connection between heritage and the people who sustain it.

Bibliography

- Britannica. (n.d.). Rajakariya. Accessed on October 22, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/rajakariya

- Cindrebay. (2024, September 28). Handcrafted heritage: Sri Lanka’s traditional arts and crafts. Cindrebay. Accessed on October 24, 2024, https://www.cindrebay.ae/2024/09/28/handcrafted-heritage-sri-lankas-traditional-arts-and-crafts/

- ICOMOS. (1988). Advisory body evaluation: Sacred City of Kandy. UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/documents/153507

- Ratnayake, P., & Mathota, S. (2020). Documenting traditional heritage conservation and management in Sri Lanka. In G. Wijesuriya & S. Court (Eds.), Traditional knowledge systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage (pp. 57–68). ICCROM.

- Smith, L., & Akagawa, N. (2009). Intangible heritage. Routledge.

- Urban Development Authority, Central Province Office. (2019). Kandy development plan 2019–2030 (Gazette No. 2129/96). https://www.uda.gov.lk/attachments/outdated_dev_plans/Kandy/English-r.pdf

- UNESCO. (2011). Recommendation on the historic urban landscape. Adopted by the General Conference at its 36th session, Paris, 10 November 2011.

- UNESCO, ICCROM, ICOMOS, & IUCN. (2023). Enhancing Our Heritage Toolkit 2.0: Assessing management effectiveness of World Heritage properties and other heritage places. Paris: UNESCO. Available under CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO license. https://doi.org/10.58337/CFZO9650

- Wijesuriya, G. (2000). Conserving the sacred Temple of the Tooth Relic (a World Heritage Site) in Sri Lanka. Public Archaeology, 1(2), 99–108. https://www.academia.edu/39378434/Conserving_the_Temple_of_the_Tooth_Relic_Sri_Lanka

- Wijesuriya, G. (2005). The restoration of the Temple of the Tooth Relic in Sri Lanka: A post-conflict cultural response to loss of identity. In N. Stanley-Price (Ed.), Cultural heritage in postwar recovery: Papers from the ICCROM forum held on October 4-6, 2005 (pp. 87–97). ICCROM. Accessed on https://www.academia.edu/13841039/The_restoration_of_the_Temple_of_the_Tooth_Relic_in_Sri_Lanka_a_post_conflict_cultural_response_to_loss_of_identity

- Wijesuriya, G. (2020). Conservation and management of heritage: Alternative theoretical reflections. Ancient Ceylon: Journal of the Archaeological Department in Sri Lanka, 26. https://www.academia.edu/101896137/Ancient_Ceylon_26_Conservation_and_Management_of_Heritage_Alternative_Theoretical_Reflections

- Wijesuriya, G., & Court, S. (Eds.). (2020). Traditional knowledge systems and the conservation and management of Asia’s heritage. ICCROM. https://www.iccrom.org/sites/default/files/2020-12/traditional-knowledge-systems-heritage-conservation-asia.pdf

- Kandy Esala Perahera. (n.d.). Kandy Esala Perahera. Accessed on October 24, 2024, https://kandyesalaperahera.com/

- Sri Dalada Maligawa. (n.d.). Sri Dalada Maligawa. Accessed on November 3, 2024, https://sridaladamaligawa.lk/

- Kandyan Art Association. (n.d.). Kandyan Art Association. Accessed on November 1, 2024, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kandyan_Art_Association

16. Kandyan Art Association [Flickr]. (n.d.). Kandyan Art Association [Flickr]. Accessed on November 1, 2024, https://www.flickr.com/photos/kandyan_art_association/

About the author

Lakmali Kariyawasam Katukoliha Gamage is an architect and a student in the Master of Science in Conservation program at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. Her own experience inspires this blog post with her country’s cultural practices and her participation in the Heriland Blended Intensive Programme on “Heritage and Future Landscapes,” in Gothenburg, Sweden, in October 2024.

Contact the Author: lakmalikkg@gmail.com